CITY SCHOLARS FIND LOST MAHABHARATA IN CHENNAI LIBRARY:

Published on May 15 2017 : The Times of India (Kolkata)

By Jhimli Mukherjeepandey.

Two city scholars visiting Chennai Oriental Manuscripts Library stumbled upon some palm leaf manuscripts, which turned out to be ancient Indian scholar Jaimini’s version of the Mahabharata, believed to be over 2,000 years old. Most Indology scholars had considered his works to be lost because no manuscript pertaining to Jaimini had been available in the country .

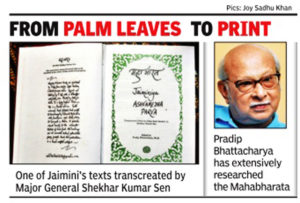

Retired IAS officer Pradip Bhattacharya and Major General Shekhar Kumar Sen, who were researching the Mahabharata, could not decipher the Grantha (Sanskrit texts written in Tamil script) on the leaves and had to bring in someone to translate it into Devanagari. “It was then that we realised we had stumbled upon a treasure trove. They were Jaimini’s manuscripts, something that had eluded all eyes for so many hundreds of years,“ Bhattacharya said.

Astudent of Ved Vyasa, Jaimini has been held in great esteem for his re-telling of the Mahabharata and there are many theories about the antiquity of his works. While for years it was thought that Vyasa’s Mahabharata was written during the Vedic times, there is no proof to authenticate this theory . Modern theorists have tried to say that Vyasa was the editor under whom scribes wrote the epic as a rebuttal to Jain and Buddhist hegemonies in ancient Indian history .Palm leaf manuscripts from that time are available as historical evidence and scholars have tried to establish the time of Jaimini’s creation to 150BC (roughly 2,200 years ago).

The scholars found both complete and incomplete manuscripts by Jaimini. Of the complete ones, they chose `Ma iravana Carita’ and `Sahasramukharavana Caritram’ to work on. “We found the National Manuscripts Mission was interested in the discovery .The Mission joined us in publishing this first ever critical edition of the texts along with the English translation in verse,“ Bhattacharya said.

Both texts deal with episodes not found in Valmiki’s Ramayana.

“Rather than Krishna’s dominance, we read about Hanuman, a Shiva devotee, as the hero. In the second book, Sita embraces the power of ShaktiKali to decimate the thousand-headed demon. These are unique stories we had never heard and are part of Jaimini’s imagination. At a time when Vishnu loomed large over our epics, you see a clear Shaivaite and Shakta influence in these two works, which are of great importance for scholars,“ Bhattacharya explained.

Courtesy : As Published in Times of India , Kolkata