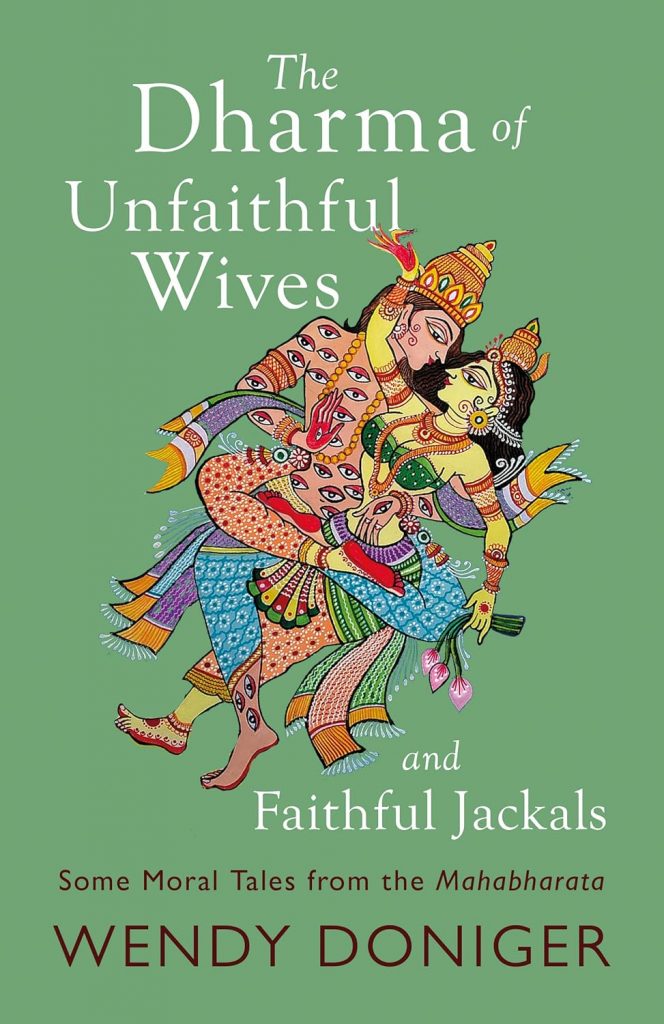

The Dharma of Unfaithful Wives & the Faithful Jackals By Wendy Doniger. Speaking Tiger, 2024, pp.222, Rs. 499.

Dr. Wendy Doniger has a penchant for catching the reader’s eye by titling her books intriguingly, e.g. The Bedtrick, The Woman who pretended to be Who She Was, etc. Her latest offering is no exception, with a provocative cover: a lovely pattachitra showing many-eyed Indra embracing Ahalya.

The book is much more than what the title suggests. It is a quite a daring project revealing that the two largest tomes of the Mahabharata (the Books of Peace and of Discipline) are not merely dreary didactic perorations but contain nuggets of unusual tales embedded within. She retells tales from the Book of Horse Sacrifice too. There are bad and good women, animal fables, fathers and sons, how Evil (rather Death) entered the world, kings including Indra and her favourite god, Shiva whom she has called, “The god of cool things” (India Today, April 23, 2013). Many of the tales contain peculiar reversals or twists that make us pause and muse.

Women are not just passive victims here, like Utathya’s nameless wife abducted by Varuna, Rukmini whipped by Durvasa, and Oghavati meekly submitting to a guest’s insistence for coitus at her husband’s command. The misogyny is justified by having women speak disparagingly of themselves. The celestial courtesan Panchachuda tells Narada: “Women indeed are the root of sin…For them none is unapproachable” (Anushasana Parva, 39.12, 17). This is because, as Raja Bhangashvana, man-turned-woman, tells Indra, coition gives women greater pleasure than men. Therefore, much to Indra’s astonishment, he prefers to remain a woman. Disha, the Northern Direction, echoes this. Though uniquely independent and unafraid of curses, she denounces women to Ashtavakra as family-destroyers, slaves of sexual desire and never deserving any independence.

Conversely, which Doniger does not note, the Mokshadharma Parva begins with the courtesan Pingala attaining enlightenment out of a frustrated tryst by conquering her senses, musing: “The expectation-less sleeps happily. Non-expectation is supreme happiness” (my translation 168.52). Rishi Bodhya names her as the first of his six gurus (Mokshadharma Parva, 171.7).

In retelling how Vipula prevented his guru’s wife Ruchi from submitting to Indra’s seduction by yogically entering her body, Doniger overlooks how the female ascetic Sulabha humbled Raja Janaka in the same yogic fashion (Mokshadharma Parva, section 320). Vipula’s allegorical encounters with symbols of day and night and the seasons are paralleled by Uttanka’s experiences (eating bull-shit; two women weaving black and white threads; a rotating 12-spoked wheel). Doniger misses this because she chooses not the original Paushya Parva version but the later Ashvamedha Parva one, which she selects to capitalise on the Gautama-Ahalya-Indra myth. Here, Uttanka’s guru is not Veda but Gautama, and the guru’s wife is not nameless but is the “notorious” Ahalya (who) “invent(ed) adultery”. Actually, Uttanka’s tale has nothing to say about women—good or bad; so its inclusion is puzzling. In comparing Vipula’s deed to dying Vidura yogically infusing himself “into his brother’s male body” (p.18) Doniger is mistaken as Yudhishthira is his nephew, not his brother.

Richika instructs his wife that his mother-in-law should embrace not a banyan tree, as Doniger retells, but a peepul (ashvattha). Nor does the mother-in-law tell her daughter that her father Gadhi wanted her to switch the “charus” as Doniger states (p.46).

Among good wives, woman is first extolled as mother in the tale of slow-to-act Chirakari who demurs when his father Gautama bids him kill his adulterous mother (as Jamadagni bade Parashurama kill Renuka). He muses that the mother is the supreme refuge and is higher than the father; that there is no offence in women whereas it is man that offends. The second instance is of Oghavati who obliges an importunate guest sexually, obeying her husband’s command never to refuse a guest anything. The husband sees her as chatteel, echoed in Yudhishthira’s pledging Draupadi as stake. So too with Jamadagni who mercilessly keeps his wife Renuka running under the blazing sun to fetch arrows he shoots. The good wife is, therefore, the subservient one. Doniger has not included here the clincher voiced by Parvati on the dharma of women to Shiva, backed up by 13 river goddesses:

“Husband is indeed woman’s deva,

Husband is friend, husband is the goal,

Equal to the husband no shelter exists,

Nor any deity like the husband.” (Anushasana Parva, 154.72, my translation)

Doniger has not noted that the episode of Durvasa whipping Krishna and Rukmini harnessed to his chariot is paralleled by Chyavana doing the same with Raja Kushika and his queen (Anushasana Parva, 53.41) with an identical conclusion. Here, too, the ideal of suffering all atrocities silently is upheld. Similarly, the princess Sukumari remains devoted to Narada although he gets a monkey’s face.

The section about fathers and sons retells the deeply moving story of Vyasa’s anguish over his vanished son Shuka. The tale of gold-spitting Suvarnashtivi is taken from the Shanti Parva version where he is devoured by a tiger but resurrected by Narada. The earlier version in the Drona Parva (section 55) is the original of the golden goose tale. Robbers cut open the prince but, finding no gold, kill one another. There is no resurrection here.

Possibly the most appealing in the retellings are animal fables (pious and greedy jackals, stupid and wise tigers, the foolish camel, the three types of fish) that stress virtue and intelligence. A unique fatalistic story about a dog and a sage states that one’s inherited nature does not change despite keeping the best company. Most akin to the Panchatantra and the Hitopadesha is the fable about the cat, the mouse, the owl, the mongoose and the hunter. Its view of life is hard-headed and unemotional: “No one is anyone’s enemy. No one is anyone’s friend…Self-interest is the most powerful factor…people protect themselves.”

Doniger does well to include the little-known story about the starving rishi Vishvamitra trying to steal an untouchable’s haunch of a dog for food telling the protesting Chandala, “One can only achieve dharma when one is alive…I will even eat what should not be eaten (to live).” However, this incident does not occur in the Kali Yuga as she writes (p.128) but when the Dvapara Yuga had just begun (Shanti Parva, 139.14).

A very shocking story is about a wicked Brahmin ignorant of the Vedas—ironically named “Gautama” (enlightened)—who devours a heron that had saved him in acute distress and robs a rakshasa king who had fed him. Despite this, when the heron is resurrected, he persuades Indra to resurrect Gautama whom he considers his friend. Gautama is cursed by the gods to a terrible hell. Character, not birth, makes a Brahmin.

One section is devoted to the fascinating tale of the origin of Death (not “Evil” as Doniger writes; from Shanti Parva section 238, not 283). Mrityu-Death is a woman, clad in black-and-red cloth formed from Brahma’s fury to lighten the over-populated earth, who obdurately refuses to kill. Her tears of misery become diseases that kill. There is an equally interesting tale about what sets a king apart from other humans. Here Brahmins slay the tyrannical king Vena and install the unknown Prithu who comes to be known as “raja” because he pleased (ranjita) the people and becomes Vishnu’s embodiment on earth. Hence the divine right of kings. One of the founders of the Lunar Dynasty, Pururavas, was also killed by Brahmins. Therefore, Parashurama is by no means the only kshatriya-killing Brahmin. Punishment (danda) is the raja’s bounden duty—even chopping off the Brahmin Likhita’s hands.

There is also a strange story about a king affronted when seven starving sages (including Vishvamitra) refuse his offer of food because accepting gifts from a kshatriya destroys ascesis. Shockingly, these sages were about to cook the corpse of that same king’s son for food to save their lives! Their cannibalism attracts no censure! The affronted king sends a female spirit to kill the sages. They are saved by Indra, disguised as sage Shunahsakha, “friend of dogs”.

Dogs have a curious double aspect in the Mahabharata. Although considered polluting, Dharma himself becomes a dog accompanying Yudhishthira on his last journey and Uttanka is offered amrita by Indra disguised as an untouchable with a dog. Sarama, the celestial bitch, curses Janamejaya because his brothers beat her son at their yajna. Hence the snake-sacrifice remains incomplete.

Several stories about Indra are retold: two versions of his killing Vṛitra and how he slew Vishvarupa, incurring the sin of Brahminicide and how he regained his throne; not by killing Nahusha as Doniger writes (p.179), but by his queen Shachi tricking Nahusha. Indra tricks the parched Uttanka out of drinking amrita by offering it in the desert as an untouchable’s urine. In the Paushya Parva Uttanka ate bull-shit that was actually amrita given by Indra. Stories of Shiva are included: how he destroyed his father-in-law Daksha’s yajna by creating Fever (jvara); how Ushana the Asura-guru came to be called Shukra on emerging from Shiva’s penis; how Skanda was born from Shiva and speared the asura Taraka to death.

Doniger writes wittily as always, showing that the two largest and most tedious books of the Mahabharata contain interesting tales. However, she does enjoy shocking. Thus, instead of describing Brihaspati and Shukra as preceptors/gurus of the gods and demons, she uses the Italian “consigliore”, implying that both groups are Mafia!

Published in the May 2025 issue of The Book Review