RETURN OF THE RHAPSODE

Pradip Bhattacharya*

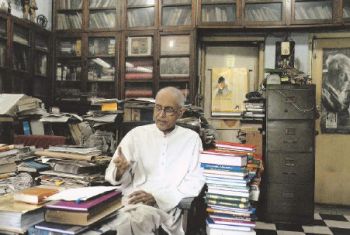

3rd November 2010 was a sad day for Mahabharata aficionados. That night saw the passing of Padma Shri Professor Purushottam Lal, 81, poet, publisher, teacher and transcreator of Vyasa’s greatest creation. Just a fortnight later his brother-in-law and classmate, Professor N. Viswanathan—thespian (stage and film), teacher, debater par excellance—also passed away. Both spent a lifetime teaching English in St.Xavier’s College, Calcutta. Those interested in the different facets of P. Lal’s personality will find much in the 70th birthday festschrift volume, Be vocal in times of beauty (Writers Workshop). Here let us share his contribution to Vyasa.

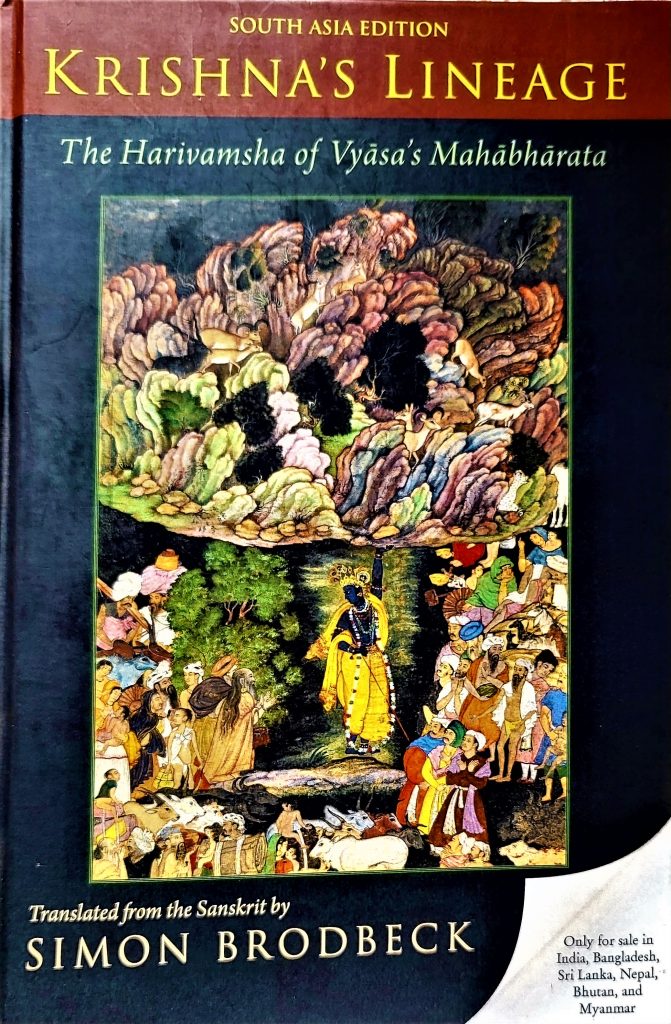

The attempts at translating in full the longest epic in the world began with H. Fauche’s French translation in 1863. He died in 1870 after finishing the 10th book (Karna Parva). L. Ballin took this forward till Book 12, when he too died. A new French translation by Guy Vincent and Gilles Schaufelbergerhas seen so far four volumes arranged thematically, not chronologically. The Russian translation started in 1941 by V. Kalyanov has completed 12 of the 18 books. In the USA, J.A.B. van Buitenen of Chicago University based his translation on the critical edition and died after finishing the first five books. A team of seven scholars is tackling the remaining parvas. The other American project of the Clay Sanskrit Library to translate the vulgate with Neelakantha’s commentary in diglot format has run out of sponsors after publishing eight parvas and parts of the rest in 15 volumes.

We have to revert to the 19th century for an almost complete English translation by Kisari Mohan Ganguli published by P.C. Roy (1883-1896). Another effort was undertaken a decade later by the Rector of Serampore College, M.N. Dutt (1895-1905). Both either omit or Latinise passages “for obvious reasons” in the Victorian ambience. In 1968 Professor P. Lal took up the first verse-by-verse transcreation of Vyasa’s monumental composition, revising it comprehensively in 2005. He had planned to finish it in 20 years, but 16 of the 18 books and half of the Shanti Parva have been published, leaving the Mokshadharma and Anushasana Parvas to be completed. In addition a Mahabharata-Katha series was published with introductions bringing out the significance of key episodes (eight have come out so far). Ganguli had P.C. Ray to sponsor him. Lal transcreated and published single-handed—a unique achivement. His is the only English version of Vyasa that shifts sensitively from verse to prose and vice-versa, following the complete vulgate text shloka-by-shloka.

No one, however, dreamt of recreating the epic as an oral-aural experience. Yet, that is what the Mahabharata is. The itinerant rhapsode Ugrashrava Sauti, son of the suta Lomaharshana (whose recitation horripilated the audience with a hair-raising experience), recites it to the hermits participating in sage Shaunaka’s great sacrificial ritual in the forest of Naimisha. Sauti reproduces what he had heard Vaishampayana recite to King Janamejaya in the presence of the composer during the intervals of the Naga-holocaust. It was in October 1999, near the turn of the millennium, that Padma Shri Prof. P.Lal, D.Litt., Jawaharlal Nehru Fellow, began to read his transcreation to a live audience. A twenty-first century Sauti had arrived in the Sanskriti Sagar library. Dictated to Ganesha, taught to Vaishampayana who recited it to King Janamejaya, that oral and aural experience was sought to be conveyed to an English-knowing audience, keeping the Indian flavour intact. Ratikanta Basu, CEO of TARA TV, realizing the signal contribution this was making in turning the world’s largest epic into a live experience, began to telecast the reading in segments. On the Writers Workshop completing fifty years of publication, the Governor of West Bengal, Shri Gopal Krishna Gandhi, released in early 2009 the first instalment of ten DVDs of the telecasts with the text in a companion volume in a gorgeously produced presentation box. Aficionados of Vyasa will be grateful to Tara TV.

Those who have read the professor’s earlier editions (beginning with monthly fascicules in 1968), or his riveting valedictory address to the Sahitya Akademi’s national seminar on the epic in 1987, will be mistaken if they give this recording a miss. The introductory talk is a completely new and brilliant overview of the key issues in the Mahabharata, unique as much for its insights as for its style. The Professor is, after all, at his best delivering a lecture. It is spiced with inimitable touches of punning sarcasm (“This is the mother of all epics; in fact, the grandmother of all epics”; “The battle of Kurukshetra—call it genocide, parricide, gurucide, suicide—whatever; such brotherly butchery!” Or, “The fathering of Yudhishthira by Vidura is one of the best kept open secrets”).

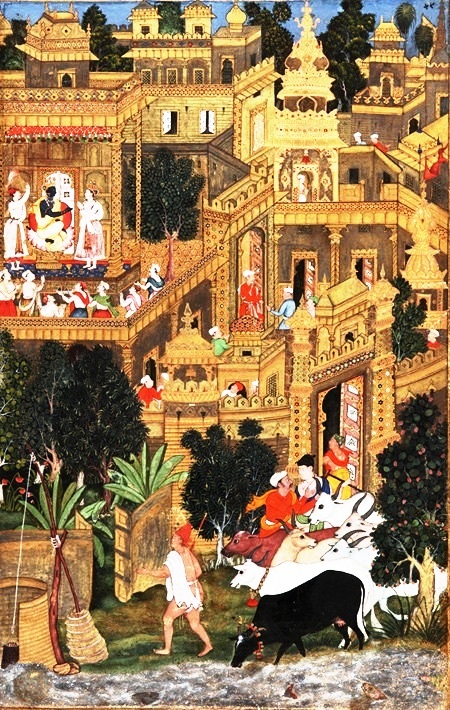

Prof. Lal begins with a question: “When, how why did a mini-Bharata, a katha of 20,000 shlokas (sic. the figure is 24000) become a Mahabharata a kavya of more than one lakh shlokas?” Sauti tells us that it took three years for Vyasa, composing daily, to complete his kavya (1.62.55, 66). Perhaps the most famous shloka of the epic, the most quoted, says Prof. Lal, is the one that says, “What is in this epic on Dharma, Artha, Kama, Moksha may be elsewhere. What is not in this epic is nowhere else” (1.62.67). Is Vyasa, then, suggesting that the kavya has an answer to every problem in life, provide a cure-all for ills of world, a universal panacea? Strangely enough, that is what he is claiming. All scriptures and shastras were weighed against it and the Mahabharata tipped the scale, “heavier than all those other respected heavies. And as it was heavier, had more “bhaara” it was known as Bhaarata. The perfect panacea.” But there is another meaning of the word that Prof. Lal overlooks: “war” (cf. Bhasa’s Karnabhaara). Emperor Akbar knew this. That is why, when he commissioned the Persian adaptation in 1582, he named it Razm Nama, the Book of War.

“What, in medical jargon, is the Rx?” queries the Professor. This is what worries Arjuna on Kurukshetra, having the deepest conscientious objection to war. Krishna gives him options: various yogas, the bloody end of the Dvapara Yuga, the extinction of the Kshatriyas. Krishna will not fight for him—that is his business. “You decide what is right for you. You are free to choose—yatha icchasi tatha kuru”, he says. Arjuna responds, “You are confusing me with bewildering choices—this isn’t fair. Tell me that one truth by which I may know you.” The point, Prof. Lal asks, is there a one truth, a single magic formula, presented by Vyasa in this epic tale?

Perhaps because of the multiple layers of meaning Vyasa insisted that his stenographer, lekhaka, Ganesha understand each word before taking it down. “For what is the point of listening without understanding and assimilating? The language enshrines ideas and values; the style is only the tool. What matters is the meaning.” Take the four purusharthas, for instance, the fourfold goal of human life. What is Vyasa recommending: should we chase after money or the meaning of money (Artha); lust or love (Kama) and at the root of both is sex and you cannot do without sex; ritual or spirituality (Dharma); run away from life or transcend it (Moksha)? For Prof. Lal, Vyasa’s one message is: transform yourself— do not deny, do not denounce, do not blame. Transform money into the meaning of money; lust into love; ritual into spiritual; escape into liberation. But, as Krishna-Narayana (divinity in humanity), tells Arjuna-Nara (humanity in divinity), “You are free to choose.” Our problem is: why does pacifist Arjuna turn militarist? Why does Yudhishthira not refuse to lie? Why does Bhima hit below the belt? Why does Arjuna kill Bhishma and Karna unfairly? Why does Nara take the ignoble way to victory, which, each time, is suggested by Narayana? Questions that tease us out of thought into eternity.

So many characters; such a bewildering Cecil B. DeMilleian cast! Who is the hero to focus our attention upon? The benediction gives some hints— though not very satisfactory.

narayanam namaskritya, naramchaiva narottamam /

devim sarasvatim chaiva tato jaya udirayet //

“We namaskara Narayana, Nara and Narottama

We namaskara goddess Sarasvati and utter “jaya”, “victory”.

Prof. Lal chooses a different version occurring in the Bhagavata Purana where “Sarasvatim chaiva” is replaced by “Sarasvatim Vyasam”, a modification added by the Suta reciting the received epic, praising the composer who, by then, is seen as a part-avatara of Vishnu. Jaimini, one of the disciples to whom Vyasa taught the epic, also uses this benediction in his version of the Ashvamedha Parva, understandably paying tribute to his guru.

The clue, Prof. Lal says, lies right before us, as in the best detective stories, and we fail to see it. He points to the first word in the opening invocation, “Narayana”, who is Krishna, the crux of the Mahabharata, without whom it is Shakespeare’s Hamlet without the prince of Denmark. It is all about “wonder-working war” in which Krishna, the omniscient hero, is present but will not fight. Nara will get no direct physical help. Narayana knows the best route to travel, but will not take us until we, Nara, tell him where we want him to take us.

“He is the conscience that clarifies the confusion. If we still remain confused that is our problem, our karma, our tragedy, our hell. You can’t blame Krishna. It is Gandiva wielding Arjuna’s decision to fight even after he is convinced that killing gurus, relatives, friends is a heinous crime.”

The startling fact is that he is given a vishvarupa darshana of Krishna’s divinity on the battlefield, yet not one of the 18 akshauhinis of soldiers sees or hears a word of the dialogue. Only Arjuna sees and hears. “It is a private struggle between his good and anti-good gunas, an inspiring conflict of conscience.” Why does he decide to fight and choose war despite Krishna’s warning that it will lead to their clans’ extinction? Krishna is the omniscient hero who advises Yudhishthira how to get Drona to lay down arms. Yudhishthira could have refused to tell the half lie. Why did he not? Bhima cannot defeat Duryodhana in fair fight unless he follows Krishna’s hint to hit below the belt. Why does he take that hint? Unarmed Karna and Bhishma are slain by Arjuna also on his advice. Why does Nara take the expedient, selfish way and reject the noble?

Yet, we find that the first Arabic summary of the epic by Abu-Saleh in 1026 AD is astonishingly innocent of this overwhelming presence. Is Krishna’s role in the war a later interpolation?

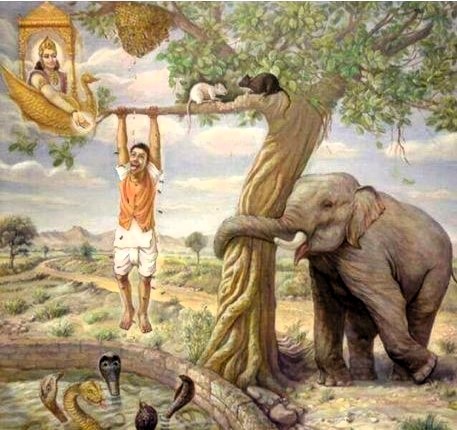

After the war Vidura, having tried to console Dhritarashtra with the story of the man in the well (that travelled to Europe to become the biblical “Barlaam and Josaphat”), teaches Yudhishthira a lesson when he wishes to commit suicide after the war finding a devastated kingdom, all kith and kin dead, by suggesting that he first find out what is common to river, tree, earth and woman. Yudhishthira turns back from suicide because he finds this out: slice a river and it flows on, fertilising the land; cut a branch and new shoots sprout; pollute the land and it produces food; exploit a woman and she gives progeny and ensures the continuity of civilization—all without casting blame or taking revenge. Physical suffering is transformed into fruitful creativity. Yudhishthira will blame no one, neither himself nor Krishna, but rule nobly, creatively.

“Learn! Vyasa urges. Learn from my life how to live as human beings should. For if you don’t, calamity awaits you and all around you. Utthishtha, stand up, wake up, learn and… charaiveti, keep moving. No regrets, no blame, no accusation; only transformation of pain and suffering into creativity and progress. That is the lesson of the Mahabharata.”

Yet, at the very end, in verses renowned as the “Bharata Savitri” why does Vyasa exclaim

urdhvabahur viraumyeṣa naca kashchich chhriṇoti me /

dharmad arthash ca kamash ca sa kimarthaṁ na sevyate //

“I raise my arms and I shout

but no one listens!

From Dharma come wealth and pleasure—

why is Dharma not practised?”

Prof. Lal provides a brief background before beginning the recitation. He gives the time of the war roughly at 3000 BC, the exact year being a matter of dispute. It is a pyrrhic victory. The kingdom is handed over to Parikshit, the grandson of Arjuna, but entrusted to Yuyutsu, Dhritarashtra’s youngest son by a Vaisya woman, to supervise. Indraprastha with its wondrous hall of illusions is left to the Yadava Vajra, Krishna’s great grandson. So who finally was the victor in this fratricidal holocaust? Duryodhana or Yudhishthira? In heaven Yudhishthira is shocked to find Duryodhana and his brothers ensconced on golden thrones, with no sign of his brothers and Draupadi! “This is not svarga!” he exclaims.

Parikshit rules for 60 yrs. His son Janamejaya organises a massive snake sacrifice to annihilate all snakes because one—Takshaka, a terrorist who plays a very important role in the entire Mahabharata—fatally bit his father. By this time a century has passed since the war ended. Janamejaya is very curious to know exactly what happened. He has heard conflicting reports about his ancestors; varying and worrying accounts about how, why and when the gruesome carnage began that ended the Dvapara Yuga, wiping out both armies.

“The entire epic is a flashback a century since the war. Janamejaya wants to know about his family tree, its roots, shoots and fruits—mula, sthula,and phula—whether sweet or bitter… The starting point of the greatest epic in the world is all about family roots, which one human being wants to know. For, how else can he know himself—for isn’t he the latest leaf on that tree?”

And so the narration by Vyasa’s disciple Vaishampayana during the intervals of the sacrificial ritual of “this story, which is also a history, an itihasa, (so it is, so it happened), the autobiography of one man (Vyasa himself), a record of one family (the Kaurava-Pandava cousins), a chronicle of one country Bharata that is India, and a symbolic universal drama of mankind slowly evolving through dissension and war to self-knowledge and peace— hopefully. It is fundamentally an aural epic spoken by Vyasa to his stenographer Ganesha who is pledged to understand every word before he takes it down.

Prof. Lal’s is the only English translation that sensitively shifts from verse to prose and vice-versa as the original demands, following the complete vulgate version shloka-by-shloka. As he does not leave out passages as the critical edition does, it is possibly the most complete edition of Vyasa’s composition that is available. However, it does not have many passages occurring in the southern and eastern recensions (such as Arjuna’s wooing of Subhadra disguised as a hermit, Draupadi’s previous births as Nalayani, Mudgalani, Vedavati, Abhimanyu’s marriage to Balarama’s daughter Surekha etc.). The discs cover the introduction (memorable for Dhritarashtra’s plangent lament tada nashamse vijayeya Sanjaya, “Then I no longer hoped for victory, Sanjaya”), the list of contents, the chapters on Paushya, Puloma, Astika (including the archetypal churning of the ocean, the wondrous story of Garuda and the snake sacrifice), the partial incarnations (including Vyasa’s birth and the war summarised), cutting off abruptly at verse 21 of section 66 of the Sambhava sub-parva recounting the descendants of Brahma’s sons.

The reading is uniformly mellifluous in Professor Lal’s impeccable Indo-Oxonian accent, interspersed with his recitation of significant Sanskrit shlokas from the original. The accompanying background music of temple bells and blowing of conches is delicately muted so that nothing interferes with the camera’s concentration on the rhapsode. One might feel that the unaltered sameness of the studio palls, but that is the price we pay in modern times for having replaced seating under verdant shadows of swaying branches with the unchanging décor of airconditioned recording studios.

Do not look, however, for colophons, chapter headings, annotations, glossaries, list of contents—the rhapsode does not need them!

Let us thrill to the evocative verses describing Creation transcreated with biblical resonance:

“At first, there was no light,

no radiance, only darkness;

then was born the egg of Brahma,

exhaustless and mighty seed of life…

from which flow being and non-being.”

Savour the riveting description of Meru, evoking profound archetypal memories:

“There is a mountain called Meru,

a flaming heap

of splendour.

Sunlight falls on it

and scatters

at the summit.

It is golden: it glitters:

It cannot be measured:…

Mind cannot

conceive of it.”

Delight in the lovely description of what happens when Garuda lets fall the massive bough on a mountain:

They fell on the ground,

these gold-bright trees,

They were coloured with the gold

of mountain minerals,

They looked like the long rays

of the flaming sun.

*****

* International HRD Fellow (Manchester), Ph.D. on the Mahabharata; IIM Calcutta Governing Board member; editorial board member of Journal of Human Values (IIMC) and MANUSHI. Retired as Additional Chief Secretary, Chairman State Planning Board, Chairman Uttaranchal Unnayan Parshat, Govt. of West Bengal.