7 P.M., 4th April 1972 at Nawabganj Police- Station, Nawabganj Sub-division, Rajshahi District, Bangladesh. Clustered round a table are: Hafizur Rahman the young deputy magistrate holding charge of the sub-division; G. Chakravarti and P.K. Samaddar, West Bengal Junior Civil Service probationers at Malda, and myself, Our objective is to hand-over 19 UNICEF trucks to the Deputy Commissioner, Rajshahi District on 5th April, and thus bring to an end Malda’s responsibility for reaching relief materials into the heart of the district.

As we wait for the trucks to be ferried across the Mahananda, my thoughts wing back to the fourth of April 1961. That day Lt. Col. G.L. Bhattacharya of the Indian Army had been shot and kidnapped from the Bongaon border by the E.P.R.; and a few months later I had found my father sentenced to eight years’ solitary imprisonment in Dacca Central Jail. Now, exactly eleven years later, the police and the magistracy of the same country and pressing me to have rice and chicken curry; the officiating SDO has been waiting to receive me without having gone home after office hours; and orders have been sent to Rajshahi Circuit House to reserve the best rooms for the “the I.C.S. (sic) officer from Malda”!

Dinner over, Rahman takes leave with old-world Muslim courtesy and we cross over to the Sibganj side of the river where the trucks are lined up to be ferried across. After nine of them have been taken over to the Nawabganj side. I fine to my total consternation that the boatmen are walking away from the ferry. Peremptorily they refuse to work any more and turn a deaf ear to all arguments and pleas that these vehicles are sorely needed by their administration for speeding urgently required food grains to scarcity areas. Some of them remark cynically, ” This India, which is pretending to be so very helpful now, will stick a knife into our back at the slightest opportunity.” It is a comment that I have heard time and again in the course of my relief work in Bangladesh, and it no longer arouses anger and disgust as it used to. I send Chakravarty and Samaddar across to the Police station to see if anything can be done. The drivers have already left for dinner in the town. So there I am around midnight, sitting on the cool, moist, sandy banks of the Mahananda, whistling to keep up my courage and my fast-sinking hopes, and ‘guarding’ the precious trucks. Much good I would be if a gang of miscreants turned up! Suddenly I hear voices raised in argument: yes, it is the resourceful Rahman, successfully tongue-lashing and cajoling the ferrymen back to work. Finally, at 2 A.M. 5th April.1972, all the trucks have been ferried across, and we speed through the stygian darkness to Rajshahi. Half asleep, I recall how it had all begun a couple of months back.

I had first met my District Magistrate, Sri S. P. De, on 15th January,1972 the day after I arrived in Malda. He promptly prostrated me with the causal announcement that I was to takeover charge of repatriating 30,000 evacuees to Bangladesh. This I somehow managed to achieve satisfactorily thanks largely to his affectionate guidance, and as a ‘bonus’ he gave me permission to proceed to Rajshahi with 5 truck-loads of blankets on 31st January, the day on which the last evacuees left Malda. That is how I got linked-up with the Bangladesh Relief work.

In Rajshahi our Liaison Officer, Sri T. K. Das, IAS showed me the notorious Goalia Club, which had been the Officers’ Mess for the Khan Army. Prisoners used to be brought here, and after the officers had had their ‘fun’, the bodies used to be dumped into pits dug in the adjoining banks of the Padma. I saw one of these mass graves with pieces of rope, torn clothes, skulls and bones still lying in it.

Sri Das told me that for tackling the crucial problem of raped and pregnant women, our government had arranged facilities for abortions since this was still illegal in Bangladesh. Unfortunately, only a few women had come forward. What was required was a dedicated band of social workers who would help these women to overcome their natural reluctance to come out into the open. Luckily it seemed that so far no social stigma had been attached to their condition.

The Indian Army was being used extensively in cordoning operations involving the Bihari population. The Biharis had been isolated and squeezed into tiny pockets. At times as many as 3000 had been packed into a small primary school without any sanitary facilities whatsoever. In one cordoning operation the Indian Army Officer had to rush out of one such school, unable to endure the stench and the filth. He told me that there was actually an inch thick layer of flies over the whole area. It was a miracle how they were still surviving in such conditions.

This situation was further aggravated in February. The Mukti Fouj had, after liberating Dinajpur, killed off around 4000 Biharis who had sided with the Khan Army and summarily forced some 75000 into trains leave the district. These people had got off at Nawabganj utterly destitute, in a condition of near starvation. In, Nawabganj, I was frankly told that they saw no reasons why the new government should feed people who had sided against it, and hence no relief doles were given to these refugees. The situation assumed such proportions that people began to go up to the hitherto sacrosanct chamber of the SDO with corpses, begging for money to cover burial expenses. This much was not refused.

The two major needs faced by Rajshahi District were shelters for returning evacuees, and food grains. Initially the evacuees were being housed in schools, but on one of my visits to Sibganj I came across the unbelievable phenomenon of boys gheraoing the local Relief Committee with the demand that the schools reopen immediately ! To meet this crisis, we began dismantling the camps we had set up for the evacuees, and sent these bamboo structures by trucks to the afflicted areas. These areas were on two broad fronts: Sibganj and Bholahat police-stations to the south of Malda; and Porsha and Niamatpur police-stations due east of Malda; and Porsha and Niamatpur police-stations due east of Malda.

My first assignment after returning from the 31st January trip to Rajshahi had been to investigate the possibilities of sending relief materials to the eastern border of Malda, the river Punarbhava demarcating the international border. I reproduce my report with the D.M.’s comments –

“Today (10th February 1972), after meeting the BDO Habibpur who had got back this morning from Porsha, we proceeded to Nitpur (Porsha P.S.) where we talked with Sarvashri Abul Hasnat Chowdhury, Chairman of the local Awami League Unit; Ikram-ul Haque, Secretary of the unit; Akhtur-ul Islam, local family Planning Officer, and many other local people. Sri Basir Ahmed Chowdhury, the local MCA, was away in Rajshahi and so could not be met.

As a result of our tour and these discussions, the following conclusions can be reached –

- Trucks can proceed along the Bubulchandi-Kendpur-Agra-Harishchandrapur route. A little dressing of the last part of the road will certainly facilitate the operation by cutting-down time taken for the trips.

- The ferry across the Punarbhava cannot possibly take across any diesel truck unless bigger boats are found. In the alternative some small petrol trucks can be ferried across. The materials can be unloaded on the price of rice has shot up from Rs. 15-16 to Rs. 26-28 per maund. These trucks to the required spots inside Porsha.

- Some 30000 evacuees, according to them, have returned to Porsha, and nearly an equal amount is also homeless (these had fled to other areas of Bangladesh). The badly needed materials are: bamboo poles and mats and some sort of roofing since no tin sheets hay or tarpaulin are available. 80 per cent. of the residences, it was claimed, have been razed to the ground. People are at present either living in schools, or packing into whatever houses are still standing.

- Diesel is acutely required for powering the 106 irrigation pumps, otherwise the prospect of a decent ‘boro’ rice crop is bleak. This year only about 50 per cent. of the land has produced a good crop, so that the western side of the river, ferried across on boats, and be carried by Further, if the fuel is brought via Agra-Harishchandrapur, the cost comes to about Rs. 100 less than if it is routed via Rajshahi.

- Food-grains are the other major problem in this area. This may also be supplied, if possible, through the Agra-Harishchandrapur route.’

The D.M’s orders on my report were as follows–

“We had a meeting at Rajshahi on 10-02-72. P.O.L and food grains are being sent to Rajshahi, Nawabganj and Natore. They may obtain quota from there. BDO Habibpur may be advised to draw up programme for despatch of shelter materials up to the river ghat. SDO Nawabganj will send an officer who will receive the materials from us. Transport to be provided from our end. Sri Rupendra Roy Chowdhury, alias Bhutu Babu of Nawabganj will do the liaison with us, as arranged with SDO Nawabganj will do the liaison with us, as arranged with SDO Nawabganj and D.C Rajshahi and Dr. Mishbabul Hak, Secretary Awami League, Nawabganj and Chairman of the sub divisional Relief Committee”.

A few curious facts that I came across during my visits to Porsha were that the local M.C.A., Basir Ahmed Chowdhury, was so unpopular in his own constituency that he was rarely to be found there! I also met a Mukti Fauj officer who was arranging for stocking the arms that they were surrendering, consisting of rifles, sten-guns, anti-personal mines etc. curiously, the Pakistani Army did not kill local people within their locality, but always took them elsewhere for ‘disposal’ so that tracing the victims later became an impossible task. The total absence of the usually prolific palm trees was rather striking, and on enquiry I was told that the Pakistani soldiers had destroyed all of them because the explosive sound made by the ripe “tal” fruit falling set-off false alarms to their guards who thought that they were under attack! Throughout my visits to this area the sumptuous and eager hospitality shown was so effusive as to become painfully embarrassing.

“Bhutu Babu” to whom the D.M. referred in his orders above was an amazing man whose exploits read like extracts from Ripley’s ‘Believe it or Not’. He was a Hindu lawyer of Nawabganj in his early thirties, holding post-graduate degrees in Islamic and Modern history from the University of Calcutta and possibly the most popular Awami League worker in the area. What struck me was his totally selfless devotion to his country and his people, and the super-human energy and organising ability he displayed.

Single-handed, without any help from official quarters, he set up a camp of 580 families of evacuees at Baraghoria in the Sibganj police station with whatever shelter materials we could supply. When ration supplies did not arrive on time, and repeated requests to the SDO Nawabganj had no effect, he simply threatened to prevent the next convoy of food grain trucks from Malda from proceeding to Nawabganj, and he promptly received his quota!

A similar incident was related by Fazlur Rahman, who had been deputed by the Nawabganj Sub-divisional committee to receive all relief materials from us on their behalf. He was an inhabitant of the village Harinagar in Sibganj P.S., which used to be a very prosperous community of about 500 weavers. All that is left of it now is a mass of rubble. Every building has been systematically destroyed, including the temples. Miraculously, the straw effigy of the goddess Lakshmi has emerged unscathed, though the temple itself has been broken down. We used to urge the villagers not to lose hope, but to set about rebuilding their homes, and look forward to a prosperous future, for the goddess had not deserted them. Rahman had been the officer-in-charge of Dacca Airport till he had been forced to tender his resignation through the persistent harassment of the West Pakistani Civil Aviation Regional Manager who had undertaken a systematic campaign to weed out all Bengalis from the staff. Rahman’s entire family played a major role in organizing the relief work in the Harinagar area. Though a devoted and indefatigable worker, he lacked Bhutu Babu’s broader vision, and always wanted me to send everything we had to this area first. I was interested to see how this gentleman, who was at least ten to fifteen years Bhuttu’s senior and a retired officer, used to unhesitatingly take orders from him and always sought his advice when in any difficulty.

If only I had had similar workers in the Porsha area! Here I found the attitudes very disappointing. During one of my visits, I found the ex-secretary of the Awami League unit virulently attacking the circle Officer (Development) for failing to obtain enough food grains for the people. 1300 mds. were lying at Rajshahi, but lack of transport (even bullock-carts were not available) and controversy over who would bear the transport costs were holding up everything. There was no effort or willingness to organize funds from the local resources, though they proudly told me that not a single farmer in Porsha owned less than 100 acres of cultivable land. Not a single mud house was without tin roofing , and there was a massive 3-storey mosque to boot. When I asked them why they did not circumvent this transport problem by going to Rajshahi through Malda ( a regular bus service was running between Malda and Nawabganj, beyond which local buses were available), they gravely explained that it was because of the 6 mile strength between Nitpur (Porsha) and Kendpur (in Malda) which would have to be covered on foot! The look on Rahman’s face (he had come with me on this visit to synchronize the allocation of relief materials between Sibganj and Porsha), was eloquent beyond words, but it had no effect. There upon I offered to remove this problem by taking the Awami League Chairman, Abdul Hasnat Chowdhury, in my jeep to Malda, from where he could proceed to Rajshahi. There was no response, beyond pressing innumerable sweets, poached eggs and thick milky tea on us. I found them more eager to feed us and show us around than to organize themselves so as to use most profitably and in the least possible time whatever relief material they got. At first they were not even sending any representative to see to it that the truckloads of material we sent were unloaded forthwith, so that a larger number of trips could be made and they could get more material within less time. Where our trucks could have made 5 trips daily, they were not making more than 2! They pleaded lack of manpower; and yet 30000 evacuees had returned to Porsha and were waiting for shelter materials! It was left to an outsider, Bhutu Babu, to suggest that the Awami League unit should call the headmen of all the Santhals (who composed 90 per cent, of the evacuees) and ask them to organize teams for lifting the material. Finally an officer was sent from Porsha who camped at the riverside and began distributing the materials on the spot.

The attitude of the people we were trying to help was another curious amalgam of gratitude, distrust and apathy. For instance, wherever I went, however devastated the area might me, sweets of magnum sizes would appear from nowhere and I would be forced to polish them off on pain of wounding feelings (it is a measure of the pressure of the work that despite these massive doses of sugar and starch I actually lost 5 kg. between January and April!). Whenever I went to Rajshahi I was given V.I.P. treatment and, much to my embarrassment, referred to as “A.D.C. Malda ” despite all my efforts to set them right as to my designation. Of course, they do not have any such post as Assistant Magistrate &Collector and hence my designation never registered in their minds. Resigning myself to it, I used to strut around in borrowed plumes feeling very self-important and thankful for this confusion because it helped me immensely in getting things done fast in Bangladesh. I will never forget the generous hospitality offered to me and other officers from Malda when we visited Dacca on 17th March, just as the meeting addressed jointly by Mrs. Gandhi and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was to start, by the District Judge of Dacca Sri Abdul Hannan Chowdhury, affectionately known as “judge-saheb” in Malda. The ‘pranhara sandesh’ and the sweet curb of the famous confectioners Maranchand-Kalachand, which he loaded us with were nothing but nectarous ambrosia (we were rather luckily of course as they had supplied the very same day the ‘Pranhara Sandesh’ which had been served to Mrs. Gandhi !).

But there was the other side of the coin too. Like ferrymen refusing to work at night to ferry across our trucks. Or that incident at the Nagarbari Ghat of Padma River, en route Dacca, Reaching there around 6.30 a.m., 17th March, we found a huge queue of relief-carrying trucks and private cars which had been lining up since last evening. It seems that there had been a big quarrel over letting Indian trucks carrying relief have priority in boarding the ferry-steamer, resulting in the stopping of the ferry service. There had originally been about 8 such steamers plying between Nagarbari and Aricha Ghats, connecting Dacca and Pabna districts, but we had successfully bombed and destroyed all but 2 of them, so that there was the inevitable long delay in services. Luckily for us, we managed to squeeze ourselves on to the very first ferry-steamer (each can carry about 6 large trucks and 8 cars) due to some vigorous ad-hoc priority system set-up by an ex-Mukti Fouj officer to whom I had discretely disclosed my identity. At both the ghats no arrangements had been made by the Government to impose any sort of order. There was total confusion and a general free-for-all, with the solitary policeman ( who just had a pair of khaki trousers to establish his identity) quietly effacing himself. And at these ghats I frequently heard irate Bangladeshis attacking India in no uncertain terms because the relief trucks insisted on being given priority (some had been waiting at the ghat for the last 3 days). Their reaction sounded curiously similar to what one hears from Indians about countries, which are pumping aid generously into India. However, these unpleasant experiences were more than compensated for by the magnificent reception we got at Dacca and at Rajshahi, where the local journalists’ association feted us, presented us with souvenirs and invited us to functions organized on the occasion of Martyr’s Day (21st February). The number of ardent and fiery young poets and writers, mostly in their twenties, was really astonishing, their bold experiments with literary forms and styles and the quality of journalism itself were most impressive.

Another aspect of the situation came out in the course of my visit with Bhutu Babu to Boalia village in Bholahat P.S. In this village 500 inmates had been massacred and it was one of Bhutu’s pet projects of reconstruction, besides the four villages he had ‘adopted’ in Nawabganj. Boalia had also been selected by some Viennese institution for reconstruction as a model village. Here I was frequently mistaken for a local official, and villagers would approach me complaining that they were getting just 125 gms. of cereals on alternate days, and that they would like to go back to ‘Hindustan’ where they had been much better looked after. The more upsetting disclosure, however, came from Moinul Haque, the local Awami League leader and a very fine worker. He begged me not to send the food grains to the M.C.A.s, who were actually selling it in the black-market instead of distributing it to the people . He was very bitter against the display of arrogance and power by these MCAs, who were actually selling it in the black-market instead of distributing it to the people. He was very bitter against the display of arrogance and power by these MCAs and told me that the P.M. was constantly being approached by all genuine Awami League workers not to give these people re-nomination in the elections, This was also the situation in Sibganj where Rahman told me that the elected representatives were more interested in smuggling and in organizing Razakar witch-hunts than in planning out the bringing of shelter materials from Malda before the returning homeless evacuees became a problem. Again, when rations were running out, they were busy deciding who should be in charge of the relief operations. Finally, at Rahman’s behest, the people gheraoed ( they have picked up this phenomenon from West Bengal and use it to great effect I found ) the M.P.A. and forced him to get them rations from Nawabganj. Even Bhutu Babu used to deplore the lack of character-building among the youth despite the bloody freedom struggle, and contrasted the single-minded dedication of Naxalites to the instability of Awami League and NAP workers. He was disgusted with the general attitude of waiting for the administration to send relief. In Harinagar, for instance, I found, when I revisited it after a month, that no attempt had been made to clear-up the debris, and use the bricks to re-build the houses, the villagers were, instead, using the devastated ruins as a showpiece for drawing sympathy and material help. Thereupon I made it clear that I would divert my supplies to other areas, and from the reports I received subsequently, this had a salutary effect.

It was in Boalia that I came to know of an unfortunate incident involving a Hindu and the local M.C.A. Sri Khaled. This Hindu, Benoy Roy, had been driven out from his house in Boalia during riots several years back, and had settled in Malda. After the liberation, Moinul Haque had invited him to return and re-occupy his property. Haque had also made the Muslims who had forcibly occupied Roy’s house, vacate it. They, in turn, had gone to Khaled who instructed the Mukti Fouj militia to drive out Roy. In the process, even Roy’s wife and daughter had been manhandled. Roy had been hospitalized in Malda, and there had been quite a lot of vehement opposition against sending any more relief to Bangladesh from a section of Malda’s society.

Another insight into the plight of Hindus in the newly liberated nation was provided by a slim girl of about 18 named Bulbul, who used to be one of the leaders of the women’s wing of the Mukti Fouj operating from Malda under Sri Abdul Hannan Chowdhury (ex-district judge, Dinajpur), and an expert with the 3-inch mortar. She told me that one Mujib could not change an attitude which had been drilled into a whole people over generations, and that even in Rajshahi, her home-town, Hindus were still in the darkness in which they had been earlier. She also pointed out that the MCAs and MPAs had forfeited the confidence of the people by fleeing the country during the crackdown, unlike the NAP leaders, and indulging in lining their own nests by dubious means during their stay in India.

What of the administration? On one of my visits to Nawabganj, the SDO, a state civil service officer, had taken me to his residence. The furnishings here, as in his office-chamber, took my breath away. The repast which followed, and he assured me that this was his normal fare and nothing had been arranged specially, had to be seen to be believed in a scarcity-hit area where most of the people were going without two square meals a day. How shabby and drab the chambers and residences and living standards of our SDOs seemed! What Bhutu Babu and others told me only confirmed my impression about the totally feudal and paternalistic character of the administration which was out of touch with the needs of the people and not geared at all to the speed and efficacy required of them in the emergency conditions prevailing. Such simple things as ensuring that their only link with India, the Malda-Sibganj earthwork road, was not snapped by rains, thus stopping all convoys of relief materials, was not snapped by rains, thus stopping all convoys of relief materials, just did not seem to register. The only alternative was to repair the Singabad-Rohanpur railway link with Malda. Even this was not receiving the top-priority attention it called for. When I met the Bangladesh Food Minister, Sri Phanibhushan Majumdar, at the Rajshahi Circuit House during my last visit, he was highly agitated over the food grains crisis facing the district, and what India could do to solve it. I mentioned that the only way out was to restore the rail-link, as bringing the food grains by trucks over the bad roads and ferries took far too much time and was also insufficient quantity-wise. The response was a vague acquiescence, without any positive reaction to show that the importance of the rail-link had even registered!

Actually, the minister had arrived to discuss the food situation in Rajshahi. His arrival itself was a fiasco. Somehow, correct information about the time of his arrival at the airport had not been received, so that there was no one to receive him! After his arrival, he and his entourage proceeded to attack the District Controller of Food violently for having failed to keep Dacca apprised about the deteriorating condition of food-stocks. The amusing factor was that the A.D.C. and other officers kept asking me, in guarded asides, whether I knew who the officers with the Minister were. They had no idea as to who the gentleman was to whom the Minister kept referring as “Secretary-saheb”: whether he was the Food Secretary, or his private secretary, or something else! And after the meeting the ADC did not hesitate to criticise the Minister and his entourage to me for their ‘arrogant and rude behavior’. What surprised me was that telegrams sent by them to Dacca about the food situation had reached the capital only after several days, as the condition of the telegraph service was very bad. I asked them why they had not thought of having the message relayed by police wireless. The ADC was quite thunderstruck by this ‘brilliant idea’. He had not heard of this despite his 20 years of service. All of which shows how unsuited the entire set-up was to tackling emergencies. The administrator’s dislike of the politician had come out in very naked terms during a meeting which the D.C., Rajshahi, had with the D.M., Malda to discuss the relief program. After the formal meeting was over, the D.C. proceeded to condemn roundly the Awami League politicians as selfish , greedy and corrupt. One of them, who had been based in Malda during the war, had been a Mukhtiyar’s clerk in the district where the D.C. was then a Deputy Magistrate. And this politician had never been able to forget this, and kept trying to assert his self-styled ‘superior’ position at all times. It seems when Lt. Gen. Arora had met the authorities, civil and political, at Rajshahi, the D.C had casually referred to “My Government’s orders”, whereupon this politician had heatedly remarked, “What do you mean by YOUR government? It is OUR government, WE are the Government”, and so on ad nauseam !

What remains to be said is my general impressions about the country and the people as such. To a driver whose nerves and patience have been stretched to the limit by the inexorable decision of Malda’s bullock-cart drivers not to leave the metalled road to motor vehicles, Bangladesh was truly a paradise. Here, at the faintest, honking of the horn, every bullock-cart magically left the metalled portion of the road and kept a respectful distance from us. This was so during my first few visits . But when I went as far as Dacca in March, I found quite a few carts refusing to give way. Acting on a hunch, I stopped my jeep and asked them- and sure enough they were evacuees who had got back from India. With Indian Customs of road-hogging jealously preserved in their hearts a signs of democratic rights and status! However, Bangladesh roads were a pleasure to drive on: I do not recall having coming across a single pothole throughout my drive from Nawabganj to Dacca and back [about 860 KM]. Possibly this was due to the lack of heavy traffic of grossly over laden trucks.

Another of the greatest pleasures of traveling in Bangladesh is a steamer-ride over the Padma as we had from Nagarbari to Aricha. It is an unforgettable sight, the blue Jamuna and the muddy Padma running in the same riverbed for miles, without the slightest mixing of the waters. And the Padma itself, with shores that cannot be sighted, dotted with specks of numerous sailing boats, bobbing up and down far away near the horizon like sea-gulls, how can I describe its majesty, serenity and beauty?

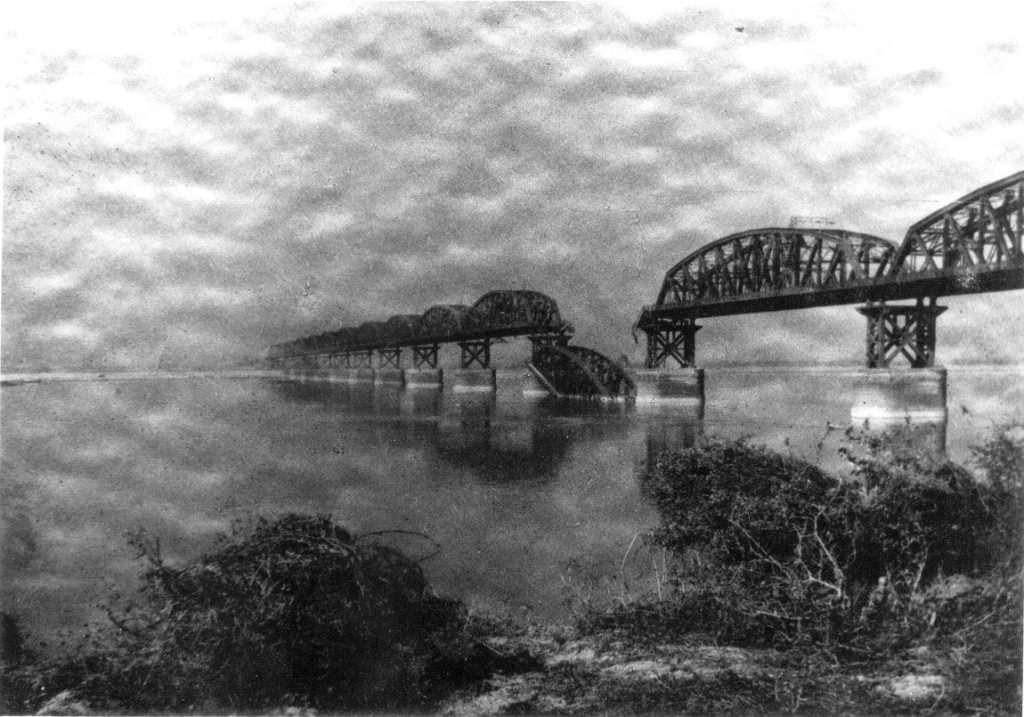

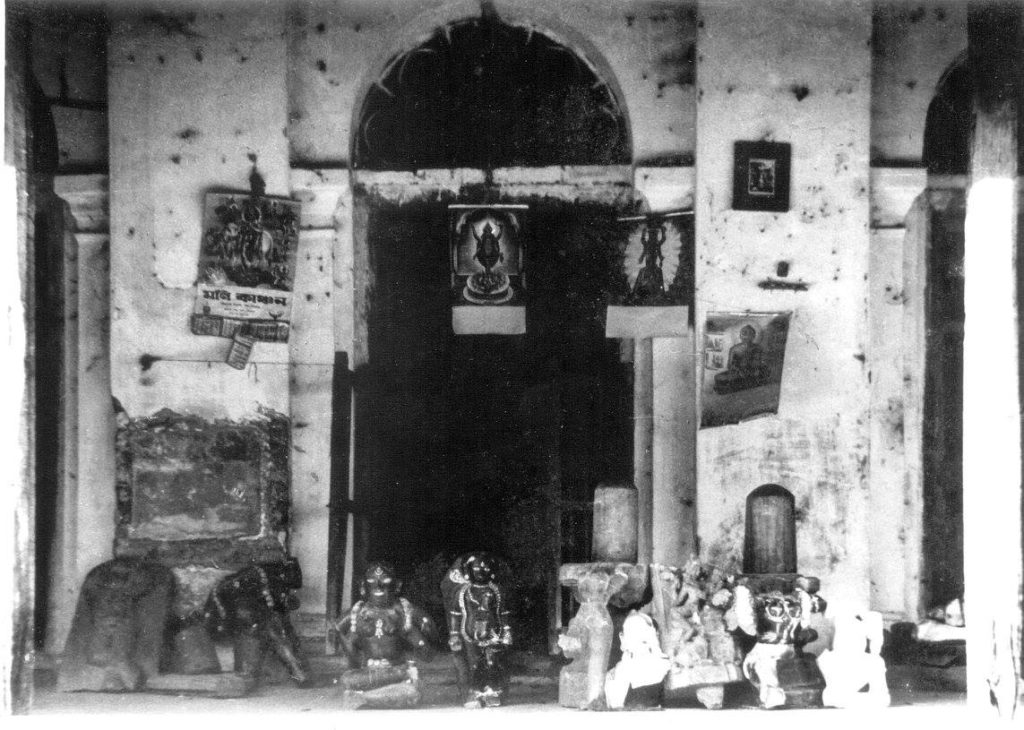

I passed through Natore, immortalised by “Banalata Sen” and Rani Bhabani, that great independent queen. I saw her Kali-temple, with the idols all ruthlessly smashed by the Pakistani Army. It had been turned into a mosque, but now it is a temple once again, and the famous “kanchagolla” sandesh is as delicious as ever. In Pabna we had the rather sad experience of searching for our SDO’s father-in-law’s residence, only to find a massive crater and totally demolished buildings at the site. Ironically, it was the work of one of our own bombs! Then there was the massive Hardinge (‘SARA’) Bridge, with the central span blown-up by the Pakistanis- a truly magnificent sight, unrivalled even by our own Farakka Barrage bridge.

But loveliest of all was Dacca. Beautifully laid out and planned, much in the manner of New Delhi, I did not come across a single beggar in the city. Kamalbari Railway Station remains an unfinished marvel. Land has been acquired all around it for a considerable distance, so that no residential buildings can come up to spoil the effect. It has soaring pillars, going up to 60-70 feet, and completely ‘mod’ architecture. On 25th March 1971 all who were present at this station had been gunned down. Now it is a favorite spot for evening promenade. There are no trains. Even more ‘mod’ is the Second Capital which was being built near the city, where the architect seems to have insisted that all buildings should have a spherical shape. It is a curious sight.

But Dacca cannot be divorced from the Steamer/Terminal bustling with people at all hours, and shops eagerly offering ‘foreign’ toiletries. We asked to see some, and were disappointed! They were all Indian! And the Rickshaws of Dacca-40,000 of them! The day we were there was unfortunately the day of the two Prime Ministers were addressing the people , and we were caught in the resultant jam for hours. The cycle-rickshaws merrily disregarded all traffic rules, brushed aside the police constable’s desperately waving hands, and went their way. The District Judge told us that it was always better to keep out of their way. Once a rickshaw had bumped into this car in its anxiety to go ahead, and its driver had promptly demanded Rs. 5/- from His Honor as compensation for damage(?) to the rickshaw, and had got the money! Prices of all household utensils and cloth were very high. Ladies lamented the non-availability of Karachi nylons which used to sell at Rs.15-20, and very cheap stainless steel utensils. Lack of supply of yarn had resulted in a shortage of ordinary saris too. But whatever the scarcity situation, there was never any shortage of writing, both creative and journalistic. The Bengali brain seemed to thrive on scarcity and work at white-hot intensity all through.

I left Dacca on a rather sad note. In 1962-63, visiting my father in the Central Jail, I had seen the famous ancient Kali-temple at Ramna Maidan. A decade later I went there again, full of expectation. There was nothing left, not even a single stone. The Pakistanis had obliterated it, as they had the Shahid Pillars, And before I left, the District Judge told me, with great anguish, how the P.O.L. they needed so very badly from India was being systematically black- marketed by some Indian businessmen who had taken up residence in Dacca and were somehow managing to divert part of the consignments for Bangladesh to their own benefit. But he urged me to come back a year later, and see that his country had really become “Sonar Bangla”. Even in this very year one could see the seeds of the golden future in he lush green countryside, the busy reconstruction of bridges and roads, and the vibrant faith and resilient hope of the people of Bangladesh.

My visit to Rajshahi to hand-over the 19 UNICEF trucks was the last of my nine trips to Bangladesh and thence forth we stopped sending relief through our own vehicles. Relationships also underwent some inevitable changes, Letters to the D.C. and A.D.C. Rajshahi, asking for various accounts never got replies. We shrugged and tried to forget the past . But I have not been able to erase memories of such wonderful human beings as Bhutu Babu, “judge-saheb”, Rahman, and the unforgettable taste of the massive “Kanshat” chum-chums of Sibganj the delectable “kanchagolla” from the shop adjoining Rani Bhabani’s Kali temple, and the nectarous “pranhara” sandesh of Dacca’s Maranchand- Kalachand!