International Journal of Hindu Studies (2018) 22:523–549

International Journal of Hindu Studies (2018) 22:523–549

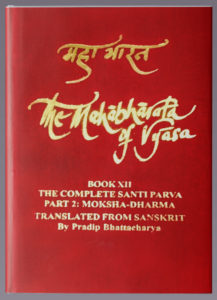

Pradip Bhattacharya, trans., The Mahabharata of Vyasa. Book 12: The Complete Shanti Parva. Part 2: Moksha-Dharma. Kolkata: Writers Workshop, 2016, 1112 pages.

In 1968 Purushottam Lal began transcreating Vyasa’s Mahabharata in free flowing English verse—indeed a mammoth enterprise. No one before him had attempted a translation of the complete epic in verse. Before his death in 2010, he had transcreated and published sixteen and a half of the eighteen books, leaving the Mokshadharma part of Shantiparva and the Anuśāsanaparva untouched. Pradip Bhattacharya took up the challenge of translating the former. This was indeed very brave of Bhattacharya as this is the toughest section of the epic, containing the essence of Vyāsan philosophy. In many ways Bhattacharya was the right person to undertake this work, given his deep and extensive study of the epic.

The book comprises a short preface, the text, and some interesting appendices: two maps, a list of stories in the Parva, and Bhattacharya’s eloquent reviews of Professor Lal’s transcreations of the Karṇaparva, Strīparva, and Shantiparva (Rājadharma). Bhattacharya’s methodology is to keep to the original syntax, translating sloka-by-sloka in free verse and prose, faithful to Lal’s objective of providing “the full ragbag version.” It is the most complete translation to date and the first in verse, conflating the editions published by the Gita Press, Aryashastra, and Haridas Siddhantavagish, cross-checked with the shorter critical edition (including the supplements), Kaliprasanna Singha’s Bengali translation (1886), and K.M. Ganguly’s first English translation (1896).

Yudhiṣṭhira, having been instructed on the principles of governance, shifts gear from Section 174 of Shantiparva (Section 168 of the Critical Edition) to ascend to the higher levels of philosophy with the question,

“O Pitamaha-grandfather, you have

spoken on auspicious

Rajadharma, the dharma of governance.

O Earth-lord, speak

now of the best dharma of ashramites!”

A series of questions follow that reveal Yudhiṣṭhira’s supremely disturbed state of mind as he tries to find solace, a method for getting over the guilt, the sorrow, and the confusion arising from the loss of all his relations and friends in the pyrrhic battle for which he holds his own greed responsible. Bhīṣma tells him everyone must try to obtain moksha, liberation, by way of detachment which can only come if one remains unaffected by worldly possessions and rises above emotions like sorrow and happiness as these are ephemeral. The true nature of the Self, ātmajnana, must be realized to obtain liberation, which emancipates from the liability of rebirth and is the highest goal of human existence. This is the only panacea.

Easier said than done! So, for the next two hundred and one chapters, Bhīṣma holds forth on how to obtain liberation, answering myriad questions from the troubled Yudhiṣṭhira, through which the vast expanse of epic philosophy is opened up. To explain the difficult concepts involved Bhīṣma uses fifty-five engaging stories and dialogues, thus establishing a tradition to be followed by Pañcatantra, Hitopadeśa, and so on. Four additional stories from the Siddhantavagish edition and two from the Southern recension are included which Bhattacharya found during his extensive research.

Devala and Pañcaśikha’s Sāṁkhya philosophy is dealt with at length. Ignorance being the root of misfortune, knowledge of the twenty-six principles is a precondition for obtaining moksha. Yajñavalkya delineates the cosmic principles in detail to Janaka who tells Pañcaśikha’s disciple Sulabhā,

“…renunciation is the supreme

means for this moksha and

indeed from knowledge is born renunciation

which liberates.

…That supreme intelligence obtained, I

free of opposites,

here indeed, delusion gone, move free of attachment.”

Interestingly, Sulabhā takes this much deeper, saying,

“Who I am, whose I am, from where I have

come, you asked me.

…If you are free from dualities of

“This is mine,” perhaps

“This is not mine,” O ruler of Mithila,

then what need of

words like, ‘Who are you? Whose? From where?’ ”

Yoga is a necessary addendum of Sāṁkhya. Through Sāṁkhya one attains knowledge and through Yoga one attains direct perception. They are complementary and equally efficacious.

Despite the Brahmanization of the epic, it reflects considerable catholicity. One becomes a Brahmana not by birth, but by gunas and consequent karma. This Parva celebrates non- Brahmanas and women like Sulabhā, Piṅgalā and Tulādhara. Much of the Bhagavad Gita is included here, covering Karmayoga, Jñānayoga, and Rājayoga, with Bhakti as an undercurrent climaxing in the Naran ārāyaṇiya.

The emergence of Shiva and the Nara-Nārāyaṇa duo as important deities are the salient developments. Shiva is established as a principal deity by getting a share of the offerings after destroying Dakṣa’s sacrifice. By Shiva’s boon Vyasa gets his son Śuka. Nara and Nārāyaṇa are incarnations of the Supreme Soul who defeat Rudra. Nārada has their darshan and initiates their worship as supra-Vedic deities.

Finally, Yudhisthira asks the last question of Mokshadharma Parvādhyāya, which was his first question too!

“Grandfather, the dharma relating to

the auspicious

moksha-dharma you have stated. The best

dharma for those

in the ashramas, pray tell me, Sir!”

Bhīṣma then narrates the story of the Brahmana Dharmāraṇya and Nāga Padmanābha. Moksha is obtained by uñchavṛtti (gleaning), by the grace of Shiva. Uñchavṛtti seems to be Vyasa’s favourite option for attaining moksha. He ends the Aśvamedhikaparva too with such a story.

The most important quality of any translation is its readability and authenticity. Most translations suffer from the use of extraneous verbiage and loss of material— traps which Bhattacharya has carefully avoided. Moreover, he has succeeded in communicating the meaning of concepts that are difficult to comprehend. One moves easily with the easy flow of his language. His poetry is excellent. It is rich yet simple and never causes one to stumble. It has the smooth continuation of a river and the cadence of raindrops, and that is what makes the translation so attractive. Consider:

“Wrapped in many-fold threads of delusion

self-engendered,

as a silk-worm envelopes itself, you

do not understand (329.28).”

The depth of research that has gone into this translation is very impressive. The only problem I perceived was the inclusion of “memorable shlokas,” which break the continuous flow. These perhaps were not really needed. The production of the book is excellent. The readers will be happy to see that the Writers Workshop continues Professor Lal’s innovation of handloom sari-bound production with gold-lettering in his unique calligraphy.

Major General Shekhar Sen Independent Scholar Kolkata, India