The birth centenary of the legendary professor of English in Presidency College, Calcutta, T.N.Sen was observed by the alumni on 9th July 2009. Some of us wrote reminiscences that were published in a souvenir. Here are my memories of this remarkable teacher of English literature.

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought…

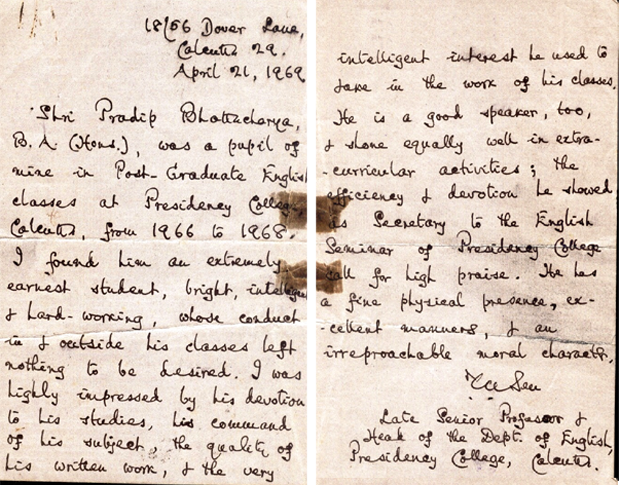

I am looking at a rare document: a small piece of blue notepaper covered with writing impeccably spaced, each letter perfectly formed. This is the character certificate-cum-recommendation Professor T.N. Sen wrote out for me at his residence at 18/56, Dover Lane when, with much trepidation I approached him as I wished to apply for the post of lecturer in English in St. Xavier’s College in 1969. I have not heard of him providing such a certificate to other students of his—perhaps they dared not ask! I guess my Xaverian brashness led me on to enter where betters dared not tread.

After graduating with Honours in English from St. Xavier’s College, when I wanted to join the Calcutta University’s M.A. course in 1966, I found that it was possible to be enrolled through Presidency College. As a Xaverian, I had been brought up on a staple diet of the impossibility of anyone but a Presidencian attaining the dizzy heights of a first class in English. The cold, hard truth of it had been brought home when that summit eluded me by two marks in Part-I and a single mark in Part-II. I was, therefore, intensely curious to find out what made the English Department of this college so very special.

I found myself the solitary “outsider” in a class consisting of four ladies [Chitrita Banerjee, later a well-known author, Indrani Chaudhuri, Anjushree Ghosh, both became lecturers subsequently, and Sunipa Basu, who joined the Indian Customs & Excise Service] and two men [Arya Gupta and Gautam Basu], all native Presidencians. I grit my teeth and was determined to stick on despite the fulminations of Dr. Amalendu Bose, the Sir Gooroodas Banerjee Professor and Head of the English Department of the Calcutta University, who demanded to know what was so wonderful in “that college” that I enrolled in it. The answer was obvious. What a galaxy of luminaries taught us: Dr. Sailen Sen, Prof. Amal Bhattacharjee, Dr. Kajal Sengupta, AKDG (Prof. Arun Kumar Das Gupta— Tarak Babu’s “onlie true begetter”) and Prof. Ashoke Mukherjee. Above them all was Prof. T.N. Sen himself: lanky, tall, appearing almost spectre-like as the shades fell when his classes began, going on well into the dark, teasing out every little nuance of Shakespeare and Yeats. Amal Babu’s remarkably clear explication of T.S. Eliot’s complicated The Sacred Wood inspired my first book. AKDG took up Timon of Athens, turning a minor play into a major experience. S.K. Sen took us through Shakespearean criticism with classically structured deliberation. Kajal-di handled Chaucer with scintillating brilliance, communicating her delight in “The Nonnes Priestes Tale” unforgettably. Prof. Ashoke Mukherjee taught Browning’s “Dramatic Monologues” in his inimitable “Do you follow?” fashion.

Much to my surprise I found Prof. Sen usually referred to as “Tarak Babu” (in St. Xavier’s College we weren’t used to anything but “Mr.” or “professor” for our teachers). He began our classes with a devastating statement delivered in his characteristic sibilant whisper: “If you have come to get the M.A. degree of Calcutta University, it is of no use as it is not worth the paper it is printed on.” Over the next eight weeks he dictated to us an elaborate bibliography paper by paper, dividing it into three categories marked “M” for ‘must read’, “D” for ‘desirable’ and “O” for ‘optional’. A more comprehensive reading list spanning the entire gamut of English Literature I have yet to come across. I used it later when teaching literature in St. Xavier’s College, distributing it to my students as an invaluable resource to be passed on.

As Tarak Babu took up Yeats’ poems on Byzantium I came to realise the vast gulf separating the University teaching from his. The charismatic Prof. P. Lal completed the Byzantium poems in two lectures, one for each; Tarak Babu took eight. The richness of that experience cannot be communicated in words. During this time I noticed a first year fresher poring over a tome in the library where Tarak Babu’s classes were held in a cubicle. It was Indrani’s younger brother, Sukanta Chaudhuri, subsequently a Shakespearean scholar of international renown. He was looking at Leonardo da Vinci’s “Madonna of the rocks” that Tarak Babu had asked him to examine, possibly in the context of Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damosel” (or was it Renaissance poetry?). That is how literature was taught by him, interlinking it with art, leading the student to explore and develop his own insights.

And then he started on “King Lear”. What a wealth of insight he held out to the eight of us (Kasturi Gupta, our senior, joined these classes too and insists it was “Othello”)! The approach was intensely textual, concentrating on extracting the last drop of meaning from every single verse. Indrani Shome, who had graduated from Presidency, used to regale me with accounts of how Tarak Babu’s teaching of “Macbeth” sent shivers up her spine in the witches’ scenes, with his long lanky arms snaking about and how the ladies were taken home in police vans for their safety when classes went on into the dark hours in those Naxalite terror times. Gautam Basu—ardent left extremist who switched loyalties to join the IAS—was a treasure trove of anecdotes, sending us into peals of helpless hilarity with his account of Tarak Babu’s ghost springing out from behind a Presidency pillar as AKDG performed the funeral obsequies, hissing, “Short line! Short line! Action needed! Ghee dao, ghee!” (Tarak Babu’s paper on “Shakespeare’s Short Lines” is a major contribution to understanding Shakespeare’s art and craft).

I remember his setting me a tutorial assignment on Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock”. True to Xaverian tradition, I put into my essay all the critical insights available from various “eminent critics”, only to be told in a sibilant undertone that I was expected not to reproduce others’ views but my own. I grit my teeth, slogged away and resubmitted my tutorial. My exercise book was returned with just one remark that left me crestfallen and considerably puzzled: “This will do”. When I asked my class-mates, they enlightened me that this meant I had achieved the expected standard. That was truly a crowning success for an outsider! This was followed by a bonus: he appointed me Secretary to the English Seminar, putting me in charge of its excellent library.

At the end of two years I found to my complete surprise that I had been placed first in the first class, with Anjushree following. And, in the paper on Romantic and Victorian poetry I had won a medal. The tradition of only Presidencians topping the Calcutta University had been broken—thanks to the unforgettable tutelage of Professor Tarak Nath Sen and his team of colleagues, the likes of whom we will not see again.