The Mahabharata of Vyasa: The Complete Karna Parva transcreated from Sanskrit by Padma Shri Prof. P. Lal, Writers Workshop, 2007, pp. 1036, Rs.1000 (hardback). Special edition of 50 copies each with an original hand-painted frontispiece Rs.2000/-

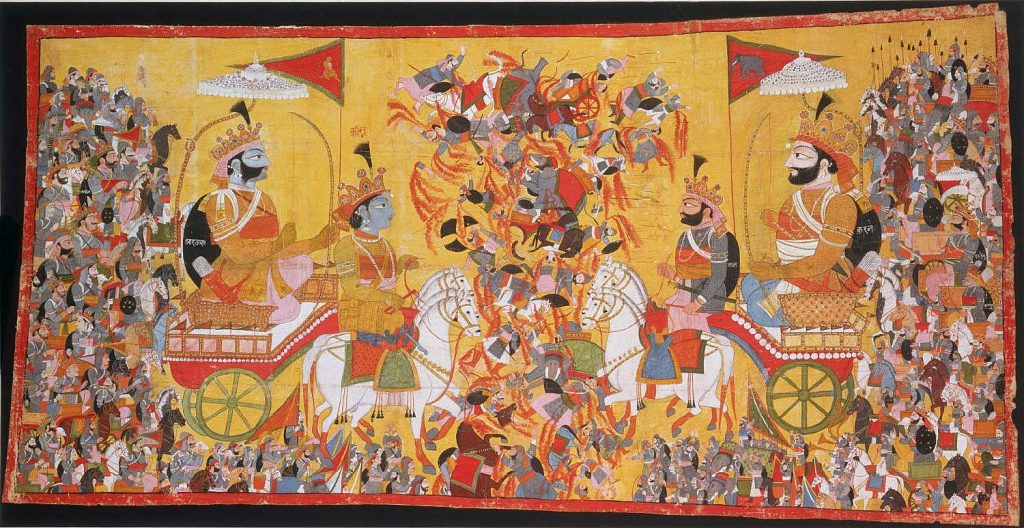

The Battle of Kurukshetra has a double climax: the Karna-Arjuna duel and the final Bhima-Duryodhana confrontation. By the time we come to the third book of battle, the elder generations have fallen; along with them their obsessions. Drupada’s craving for revenge on Bhishma and Drona has been achieved through two sons, each engendered for that purpose. Before decapitation, Drona kills the Pandavas’ two major allies: Drupada and Virata. Ancient Bahlika, Bhagadatta, Bhurishrava —all are slain. Nothing stands in the way of Duryodhana’s eagerness to have Karna command his forces, a desire that he has had to put off twice over. Despite Karna having fled the field at least thrice during Drona’s generalship, Duryodhana holds fast to a blind faith in his invincibility with a drowning man’s desperation.

The reader will notice a unique feature about Prof. Lal’s style of transcreation: the use of doublets wherever Vyasa does not use the usual name of a character. Thereby, with masterly skill he interweaves explanations obviating the need for annotations. Thus, “river-born Apageya-Bhishma” explains the original’s “Apageya”, simultaneously indicating that it is another name for Bhishma. He does so for technical terms too: Aksha-axles, Kubara-poles, Isha-shafts, Varutha-fenders. Where explanations of weaponry are needed, e.g. the fourfold science of weaponry, the transcreation provides it in rhythmic free verse [2.16]:

The free

Those released by the hand

Like arrows;

The unfree

Those clutched by the hand

Like swords;

The machine-free

Those shot by machines

Like fire-balls;

The free-and-unfree

Those which return after released

Like Indra’s thunderbolt.

Doublets make abstruse weapons self-explanatory: prasa-barbed darts, risti-swords, bhushundi-firearms, tanutra-armour. So, too, for ornaments: angada-armlets, keyura-bracelets, hara-necklaces. However, “33-lord Indra” (p.237) is hardly mellifluous!

The images in this book have a distinction of their own. With Arjuna’s arrow stuck in his forehead Ashvatthama looks “like the rising sun/with its rays shooting upward”. An elephant struck with 100 arrows glows like a mountain with its trees and plants aflame in a forest-fire at dead of night. Warriors target Arjuna like countless bulls attacking a single one to mount a cow in season. The battlefield blossoms like a lake lovely with white lily and blue lotus faces of beheaded warriors, glowing with splendour as if decorated with garlands of constellations in autumn. Bloodied faces are as lovely as split pomegranates, their teeth the seeds. Like a monsoon field with red shakragopa-beetles, or a young dark-skinned girl’s white dress dyed with red turmeric, or a free-roving courtesan flaunting a crimson dress, crimson garland and gold ornaments—such was the earth. Karna’s snake-arrow blazes in the sky “like the centre parting/in a woman’s hair”.

The book begins with the Kauravas ruminating over how they dragged and demeaned Draupadi. Then in just five verses it wraps up the death of Vrisha (Karna). Although Dhritarashtra, Bhima, Duhshasana, Krishna all recall the dragging and insulting of Draupadi at different stages in the battle, none refers to any attempt to strip her. That episode was interpolated to accentuate the wickedness of the Kauravas and exalt the divinity of Krishna.

An intriguing feature of the battle is that attacking and even killing weaponless charioteers draws no criticism. Even Krishna is wounded by Ashvatthama and Karna. Satyasena’s javelin pierces through his left arm making him drop the whip and reins. The charioteer’s role as advisor is well brought out where he advises Dhrishtadyumna who is bewildered by Kripa’s assault. Section 26 provides a rare picture of Kripa in irresistible full flow.

In the beginning, Janamejaya questions Vaishampayana about Dhritarashtra’s reaction on hearing of Drona and Karna’s deaths. After Karna was killed Sanjaya rushed at night to Dhritarashtra and related the aftermath of Drona’s death till the fall of Karna, his sons and brothers and how Bhima slew Duhshasana and drank his blood. His very marrow horripilating, the blind king wants to know what is left of both armies. From the reply a pattern emerges: the inhabitants of Krishna’s birthplace and youth—Surasenis and Narayanas of Mathura and Gokula—chose to fight against him alongside the kings of the east and north-east (Kalingas, Bangas, Angas, Nishadas) who led elephant armies against the Pandavas. Satyaki killed the Banga, Sahadeva the Pundra and Nakula the Anga ruler. Those from the south, west and north-west suffered annihilation at Arjuna’s hands. Among southerners, Pandya alone was pro-Pandava, whom Sanjaya calls “world-renowned”. When Dhritarashtra asks him to justify this, we have a sudden description of his savage attack on the Kauravas in section 20 in 44 verses, till he is killed by Ashvatthama, which appears to be very much of a command performance. It is interesting that in the southern recension of the epic Chitrangada is a Pandya princess.

We are given new information in 2.13 that Parashurama taught Drona from early childhood. Confirmation regarding the relative novelty of the Mahishamardini myth comes in 5.56 where, as in the Vana Parva, it is Skanda, not Durga, who is the buffalo-demon’s slayer. A typical epic exaggeration occurs in 5.4 where Sanjaya says that Bishma slew an “arbuda” (a crore) of soldiers in ten days. As he slew ten thousand daily, the total is a lakh and not “ten crores” as translated (p.24). In 5.14 Sanjaya says that Draupadi’s son (unnamed) slew Duhsasana’s son—possibly Abhimanyu’s nameless killer—but there is no other account of this. Paurava, a Kaurava ally whom Van Buitenen regards as a historical reference to Poros, had been defeated by Abhimanyu and now falls victim to Arjuna (5.35). We usually overlook the fact that Kunti too was a loser in the battle. Kuntibhoja’s descendants were all slain by Bhishma, who also accounted for the Narayanas and Balabhadras (6.22). Drona slew both brothers of Kunti, Virata, Drupada and their sons and most of the notable kings in just five days. Bhishma in ten days mostly concentrated on reducing the Pandava army.

The Karna-Arjuna battle is obviously the high point since Sanjaya describes its carnage as rivalling the mythical duels of Indra-Vritra, Rama-Ravana, Naraka-Mura-Krishna, Kartavirya-Parashurama, Mahisha-Skanda, Andhaka-Rudra, Indra-Bali, Indra-Namuchi, Vasava-Shambara, Mahendra-Jambha. Karna, of course, has been possessed by Naraka by now. Underlying the duel is the puzzling Rigvedic myth of Indra routing Surya and taking his wheel. A reverse epic parallel is Sugriva (born of Surya) defeating Bali (Indra’s son) in the Ramayana.

Ironically, Dhritarashtra’s lament (9.21): “you plan something/Fate plans differently./Aho!/ Fate is all-powerful./Kala/cannot be questioned” is no different from what Krishna had told Yudhishthira: “What is possible for man, I can exert to the utmost; but over fate I have no control.” Dhritarashtra makes the telling point (9.39) that both Bhishma and Drona were killed through exceptional deceit: Shikhandi shot down Bhishma who was not fighting him and Drona was beheaded when in yoga. Significantly, Dhritarashtra points to the Panchalas as responsible for both heinous deeds, exposing what underlay the Pandava-Dhartarashtra rivalry. He mentions often the awe in which the Pandavas held Karna, especially Yudhishthira who went sleepless for 13 years, haunted by fear of Karna. Even Bhishma, Kripa, Drona have never shamed him in battle like Karna. Twice Dhritarashtra recalls Karna taunting Draupadi that she is husbandless in the very presence of the Pandavas—such was his self-confidence. He calls Karna “the never-retreating hero”, overlooking how he was routed from the field several times. Interestingly, Karna is called Bibhatsu (49.25) when he recovers after having been knocked unconscious by Yudhishthira’s arrow, deliberately equating him with Arjuna.

Arjuna’s recurrent laxityin this parva lends support to the Gita being a later addition. In section 16 Ashvatthama’s feats wax, Pinaki-like, while Arjuna’s wane, enraging Krishna who berates Arjuna for being sentimental about fighting his guru’s son. Arjuna flares up only after Krishna, blood streaming from his body, asks him not to spare Ashvatthama. In section 19 Krishna has to exhort him to stop playing games with the Samsaptaka kamikaze squad which even catches hold of them and Keshava fells them bare-handed. Susharma succeeds in making Arjuna slump down. When Ashvatthama nonplusses Arjuna again, Krishna exclaims: “very strange, Partha-Arjuna/Very strange—what I am seeing now./…Drona’s son/Seems to be the better man today….Is your fist/a little flabby or what?” (56.135-138).

The carnage after Arjuna has been tongue-lashed becomes the occasion for a survey of the field by Krishna (19.28-53, repeated in 58.10-41), as he had done after Jayadratha’s death in the Drona Parva (section 148), ending with him praising Arjuna’s performance as worthy of the king of the gods. The field becomes such a morass that even Arjuna’s chariot-wheels get stuck (27.40-41)—a doublet of Karna’s plight later. In 90.57 Krishna heaves the embedded chariot wheels out of the ground with both hands, unlike Shalya who does not even make an attempt.

Section 29 depicts a rare duel between the rivals for the throne. The normally diffident eldest Pandava knocks Duryodhana unconscious. Surprisingly, Bhima prevents him from administering the coup de grace because that would nullify his vow. Similarly, when Bhima knocks Karna unconscious in section 50 and rushes to slice his tongue for his insults, Shalya stops him, reminding him of Arjuna’s vow. Shalya does a fine job as a double-agent by saving Yudhishthira twice from being captured (sections 49, 63). Strangely enough, Dhritarashtra never asks Sanjaya why Karna did not capture Yudhishthira after defeating him, which would have ended the war, as Drona had planned. To comprehend Karna’s complicated psyche we have to recall what he told Krishna in the Udyoga Parva. Karna is a man at war with himself, so memorably portrayed in Shivaji Sawant’s epic novel Mrityunjaya. One part of him knows that the victor has to be Yudhishthira, the righteous ruler; the other’s very life is chained by gratitude to Duryodhana.

Prof. Lal succeeds admirably in conveying the variety in battle descriptions as in 28.36-40—an excursion into vivid description of fist-fights compellingly Englished:

Hands raised high

Brought crashing down

On the foe!

A battle of tugged

And ripped hair-tufts!

A battle of bodies

grappling and wrestling!

Smell, touch, rasa-taste—

Stench of blood!

Feel of blood

sight of blood,

gush of blood,

Everywhere crimson blood (49.104).

Like the Valkyries, Apsaras take the dead soldiers in chariots to heaven (49.93). Alongside this, Vyasa repeatedly stresses the horrific meaninglessness of war: the soldiers who died, killing friend and foe, did not know who and what weapons killed them (28.41).

The greatest challenge Duryodhana faces is Karna’s request for a charioteer equalling Krishna, for he finds that otherwise he cannot match Arjuna. Duryodhana lays on flattery with a trowel to persuade Shalya, comparing him to Brahma whom the gods considered Shiva’s superior and therefore chose as his charioteer. His lengthy exhortation contains a mini-myth of Shiva engaging Parashurama to annihilate the Daityas (section 34). Shalya finally succumbs when Duryodhana praises him as Krishna’s superior and declares that, if Karna dies, the Kaurava army will be in his hands.

Sections 40-45 contain Karna’s lengthy diatribe against Shalya’s people, the Madras, for being wicked like mlecchas, promiscuous, utterly untrustworthy. He particularly condemns the women (tall, fair, dressed in soft blankets and deer skin) for urinating while standing like camels and donkeys and being indiscriminately lustful, gluttonous and drunk. He tars the people of Gandhara and Aratta/Bahika (the land of five rivers) with the same brush. It is curious that Bhishma should have paid heavy bride-price for Gandhara and Madra princesses! Karna voices the prevailing prejudices: the Kauravas, Panchalas, Shalvas, Matsyas, Naimishas, Koshalas, Kashis, Angas, Kalingas, Magadhas and Chedis are the civilized peoples (no mention of Bangas), while the Bahikas/Madras are the filth of the earth, located along Vipasa (Beas) and Sakala (Sialkot). The easterners are servants, the southerners bastards, the Saurashtrans miscegenous. Shalya’s retort is gentlemanly, showing up the bitter gall spewing from Karna. Dhritarashtra, too, mentions his acid tongue. It is his profound sense of injured merit that fuels this vomiting of poisonous speech. No wonder his tongue is said to be his sword!

During this abusive exchange Karna recalls the two curses that alone trouble him and is confident that unless his chariot wheel gets stuck, Arjuna’s death is assured. In this context he voices his life’s goal: “I was born for valour, I was born/to achieve glory” (43.6).

Krishna, wanting Karna to tire himself out fighting before he meets Arjuna, diverts to meet the demoralised Yudhishthira and brilliantly tackles Arjuna’s peculiar attack on Yudhishthira. In resolving the issue, Krishna makes a signal pronouncement that is quite distinct from the philosophy of the Gita: to lie is better than to kill (69.23) because ahimsa is the supreme virtue (69.57). He enumerates when lying is permissible: in marriage, love making, to save life, when all one’s wealth is being stolen, to benefit a Brahmin or when joking (69.33 & 62). It is childish to think that truth should be spoken no matter what: “He knows dharma who knows/when to speak the truth/and when to lie” (69.35). This is no Kantian categorical imperative, nor is it clever sophistry. To illustrate, he narrates the stories of the uneducated hunter Balaka and of the learned hermit Kaushika, vowed to truth-speaking, but lacking knowledge of practical dharma. Dharma is so called because it supports and protects. Hence lying to protect dharma is not a lie (69.65).

Section 72 is a long harangue by Krishna to extricate Arjuna from the morass of depression following this encounter. Urging why Karna must be killed, Krishna cites a fascinating reason: because his hatred of Pandavas is not motivated by self-interest. Krishna tells Arjuna that Karna is possibly his superior, has all the qualities of a warrior, is 168 finger-lengths tall, long armed, broad chested, proud, very strong. His sword is his tongue, his mouth the bow, arrows his teeth. Like a wall of water shivering into rivulets when striking a mountain, the Pandava army disperses before Karna’s might. Vyasa deliberately builds up Karna’s prowess hereafter.

In section 73 Krishna burns with fury recalling how Karna, so mangled and dazed by Abhimanyu’s arrows that he wanted to flee, caused the boy’s death by slicing his bow on Drona’s advice so that five others could kill him (there is no mention of Duhshasana’s son smashing his head). Frequently Krishna has to provoke Arjuna by reminding him how Karna abused Draupadi and the Pandavas vilely. He bids him kill Karna’s son to demoralise him. Arjuna now abandons his self-flagellation saying, as in the Gita, “Govinda, you are my lord and master” (74.1-3). Yet, when Karna’s Bhargava missile counters Arjuna’s Indra missile and decimates the Panchalas, Arjuna needs to be enthused first by Bhima and then by Krishna who reminds him that in every era he has killed demons, specially Dambodhbhava (whose overweening pride Krishna narrated in the Kuru court). The Arthashastra VI.3 also cites him as one of those monarchs who perished due to arrogance. Krishna even bids Arjuna use his razor-edged Sudarshana discus. Again, as in the Gita, Arjuna awakens to his life’s mission and uses the Brahma missile, which Karna promptly neutralises! In disgust, Bhima advises him to try some other weapon. Never have we seen Arjuna thus foiled.

Characteristically, Arjuna is the true hero who always admires his opponent, as in 79.9,11: how splendid raja Duryodhana looks beside Karna with Shalya urging the horses! After Duhshasana’s death, Shalya encourages Karna in true heroic style: “Win and gain glory, lose and gain heaven” (84.16).

Section 76 paints a unique picture of a demoralised Bhima. “I am troubled”, he says, being all alone, surrounded by enemies. He seeks encouragement from his charioteer Vishoka, who re-inspires him and is gifted 14 villages, 100 slave girls, 20 chariots. Bhima creates a river of blood. Shakuni suddenly emerges as a mighty warrior who kills Bhima’s charioteer, catches his lance in mid-flight and flings it back, piercing his left arm. Bhima knocks him down but does not kill him, because he is Sahadeva’s portion.

However, in section 82 all Karna’s prowess cannot prevent Duhshasana’s horrific death, or that of his son Vrishasena. Duhshasana mocks Bhima, reminding him how the Pandavas fearfully lived in the lac house, scrounged for food in the forest obsessed with fear, hiding in caves and deceived Draupadi “to choose as husband Phalguna”. Then he hits very hard: “Then you scoundrels/ did something similar/ to what your mother did./ Draupadi chose only one,/ but all five of you/ shamelessly enjoyed her” (82.39-40). He even fells Bhima, who is temporarily unable to hit back. Finally, Bhima strikes him down and invites Karna, Duryodhana, Kripa, Ashvatthama, Kritavarma to try to stop him from killing Duhshasana. Though laid low, Duhshasana smiles with fury and proudly displays the hand with which he dragged Draupadi by her hair in public. Bhima rips out that arm, pummels Duhshasana with it, rips open his chest, drinks the blood, beheads him and roars that nothing is as sweet—not mother’s milk, honey, ghee, flower-wine, sweet curd, butter, nectar. Sipping the blood he dances, terrifying onlookers who flee thinking him to be a rakshasa. One vow fulfilled, he looks forward to offering the yajna-beast Duryodhana as sacrifice, crushing his head with his foot before all Kauravas (83.50). This image of war as a sacrifice, repeated at critical intervals, is rooted in the panchagni vidya celebrated in the Brahmanas as a symbol of Prajapati the Creator’s self-devouring to create the cosmos, the serpent biting its tail.

At Nakula’s urging—humiliated by Vrishasena—Arjuna slays Vrishasena before Karna’s eyes. Krishna paints a lovely picture of Karna advancing (86.6-10). As in the Gita, Arjuna says that he will win “Because you, the guru of all the worlds are pleased with me” (86.17). Karna-Arjuna are both compared to Kartavirya Ajruna, Dasharathi Rama, Vishnu, Shiva, with finest chariots and best charioteers driving white horses. While warriors watch, “the two heroes/played the dice-game of war,/for victory/or defeat.” (87.36).Karna, the hero of “the other”, is backed byAsuras, Yatudhanas, Guhyakas, Pishacas, Rakshasas, minor serpents, Vaishyas, Shudras, Sutas and the mixed castes. Brahma and Shiva jointly foretell Arjuna’s victory. The line-up of celestial beings shows clear evidence of interpolation from shlokas 39 to 63 and again from verses 64 to 99 in section 87. Shalya boasts that if Karna falls, he will alone slay Krishna-Arjuna. Krishna-Janardana (transcreated appropriately as “punisher of the people” in 87.119) announces that if Arjuna falls, which is impossible, he will crush them barehanded.

Arjuna’s bowstring snaps, Karna pierces him and Krishna, ripping apart the Pandavas like a lion does a pack of dogs. “Invulnerable the bow/of Karna and tremendously/strong its bowstring” whereby he pulverises all of Arjuna’s missiles (90.3). Arjuna slices off Shalya’s armour, wounding him and Karna severely. Bathed in blood, resembling Rudra dancing in a cremation ground, Karna pierces Krishna’s armour with arrows that are the five sons of Takshaka’s son Ashvasena whose mother Arjuna killed at Khandava. Infuriated, Arjuna riddles Karna’s vulnerable parts so that he is in agony. Yet he stands straight. Unable to excel Arjuna, he uses the snake-mouthed arrow which Ashvasena enters yogically. Krishna saves Arjuna by pressing down the chariot so that only his diadem is knocked off. Hubris-ridden Karna arrogantly refuses to re-shoot the same arrow, just as he refused to re-aim when urged by Shalya, even if it could kill a hundred Arjunas. Karna, his armour shredded with arrows, faints, glowing like a hill “covered with a wealth of blossoming ashoka, palasha,/shalmali and sandalwood”, dazzling like a mountain “bursting with the beauty/of entire forests/of blossoming karnikaras” (90.77-78). When Arjuna does not press his advantage despite Krishna’s repeated urging, Karna recovers, his morale plummeting as fails to recall Parashurama’s missile. Simultaneously his chariot wheel gets stuck. Raising his arms he laments, “Dharma knowers proclaim that dharma protects its cherishers. I have always cherished dharma, but it is not protecting me—it protects none.” This is a remarkable anticipation of Vyasa’s Bharata-Savitri Gayatri: “I raise my arms and I shout/but no one listens! From Dharma flows wealth and pleasure–/why is Dharma not practised?” Vyasa urges not giving up dharma up for pleasure, fear, greed, or to save one’s life, which is precisely what Karna is doing. Arjuna’s arrows have bewildered him and Shalya; his mutilated body refuses his bidding.

Here an interpolation occurs. In verse 82 Arjuna readies the Raudra missile and Karna’s wheel sinks in shloka 83. This recurs in verse 106. In-between are 23 verses in which Karna wounds Krishna and Arjuna, cutting Arjuna’s bowstring 11 times. Failing to extricate the wheel—Shalya doing nothing—Karna weeps in frustration and begs Arjuna for time, appealing to his heroic code. It is Krishna who responds, knowing Arjuna’s weakness where the heroic code is concerned. Thrice he recalls the insult to Draupadi and other un-dharmic deeds of Karna, who is shamed into silence. Krishna’s words arouse Arjuna’s fury, but Karna successfully counters whatever he shoots and simultaneously tries to free the wheel. Hit hard, Arjuna lets slip the Gandiva and Karna now tries to free wheel with both hands (which Krishna had done successfully earlier). Krishna commands Arjuna to behead Karna before he climbs back into his chariot. Here verses 34-40 are interpolated because, instead of beheading Karna, Arjuna shatters his flag! The death-dealing dart is described as charged with Atharva-angiras energy.

Karna lies headless, hundreds of arrows sticking in him like Bhishma. His body, is “all adazzle,/like molten gold,/like fire, like the sun,” and spectators wonderingly exclaim, as with Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, “but he is alive!… To whoever asked,/he gave;/he never said no… always the giver” (93.45, 47). Yudhishthira feels that he is reborn and will be able to sleep in peace that night. We never get to know why Vasusena was named Karna. He is Vyasa’s only character conforming to the Indo-European hero prototype: the eternal solitary with the motto of the Senecan tragic hero, “I am myself, alone!”

After Karna’s death Shalya, who had boasted he would slaughter Krishna and Arjuna should this happen, flees. Duryodhana takes a stand behind an army of 25000 which Bhima decimates. Having failed to rally fleeing troops, Duryodhana all alone faces the Pandavas and Dhrishtadyumna. The end is impending.

Pradip Bhattacharya retired as Additonal Chief Secretary and specialises in comparative mythology