Wendy Doniger: Winged Stallions and Wicked Mares, Speaking Tiger Books, 2021, pp. 332, Rs. 699/-

A passionate lover of equus cabalus, Doniger’s latest book brings together several of her past writings with fresh research focussed on how horses feature in Indian life and imagination, past and present. Serendipitously, horses and India cantered simultaneously into her life when she was 22. How that happened is related in her Preface dedicated to Penelope Chetwode Betjeman, a true-born equestrienne, Field Marshal Chetwode’s daughter, after whom the main hall of the IMA is named. The book is split into 13 chapters, including a study of the “Ashvashastra”, embellished with as many as 42 illustrations, many in colour for creating the desired impact.

Doniger clarifies her position with the dramatic aplomb so characteristic of her writing: “No Indus horse whinnied in the night.” The predominant position of the horse in the Rig Veda is completely missing from the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) which, she states, was “neither invented nor destroyed (by) Indo-European (IE) speakers.” On the other hand, wherever there are IE speakers, there are horses. The earliest book dealing with horses is composed by a Mittannian named Kukkulis, Master of the Horse of the Hittite king Suppilulliumas around 1360 BCE. Simultaneously she admits that there is evidence in megalithic burial mounds in the Deccan and in the Bhimbetka caves near Bhopal of pre-IE domestication of horses ante-dating the IVC. She also admits the existence of horse-bits in Maharashtra and south of the Narmada during the IVC period suggesting “an extensive network of horse trade from northwest India” from the Middle-East. Incidentally, horses are also said to be unknown in Africa till the Hyksos conquered Egypt in mid-2nd millennium BCE, which leaves the puzzle of the drowning of the Pharaoh’s army of chariots in the parting of the Red Sea.

Without citing supporting evidence Doniger accepts Witzel’s assertion that commoners rode horses while nobility drove chariots. The earliest Babylonian friezes and the ancient epics depict horse-drawn chariots and not horses being ridden. The common European icon of St. George on horseback killing a dragon is also found in a 10th century image in Tamil Nadu of a winged horse stamping upon a five-headed serpent, recalling the Rig Vedic myth of the Ashvins gifting Pedu a snake-destroying horse. Other than the myth of the birth of the Ashvins from Saranyu as mare and Martanda as stallion, Doniger does not explore the “horsey-ness” of these archetypal physicians and why, despite divine birth they are deprived of drinking Soma until Cyavana compels Indra to agree.

Doniger asserts that the Vedic horse symbolizing the swiftness of force came to represent unbridled passions in the Upanishads. She has the horse representing “Aryas” ranged against the indigenous Indians called “dasyus” associated with the serpent Vritra. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad envisages the cosmos in the form of a horse. It is Vishnu as horse-headed Hayagriva who rescues the Vedas and Dadhichi who reveals to the Ashvins the secret of Soma through the head of a horse that they implant on him. Alongside these we have the horse-headed men and women (“kimpurusha/kinnara”). The “Shishupalavadha”, however, specifies that while the “kimpurusha” is a horse-headed human, the “kinnara” is like the Greek Centaur, a human head upon a horse’s body. The “Mahavamsa” tells of a mare-headed “Yakkhi” who eats travellers and shuts up a Brahmin she loves in her cave, like Odysseus and the Cyclops Polyphemus.

Whereas the Vedic stallion is virile and sacred, its wanderings signifying imperial ambitions of the owner, the mare was seen as insatiable and evil, the archetype being Saranyu who abandons husband and children. In the Mahabharata she becomes the underwater doomsday fire, “vadava-mukha”, the mare’s mouth. Significantly, the “Kamasutra” has a sexual position called the “mare’s trap”. Through the simulated intercourse with the sacrificed stallion in the Ashvamedha yajna the chief queen supposedly transfers its virility to the raja. The obscenity may have led to its discontinuance as recorded in the Harivamsha, revived by Pushyamitra Sunga in the 2nd century BCE.

In the Mahabharata, much more than the Ramayana, horses, birds and snakes are interlinked right from the wager between snake-mother Kadru and bird-mother Vinata on the divine steed Ucchaihsravas that emerges from the churning of the ocean. Later there is the myth of 800 horses each with one black ear emerging from the sea sought for as guru-dakshina by Vishvamitra from Galava. It is Agni as a horse who rescues Uttanka from the underground world of snakes who have stolen the divine earrings he was carrying as his guru-dakshina. In analysing this tale (p.62) she describes him as seeing a black horse with a white tail whereas the text states that he saw a splendid steed with a man dressed in black cloth. Nor is it the queen in the underworld who gives him the earrings (p.63), but Paushya’s queen. Doniger recounts a Maharashtran myth of Kalbhairi who finds a similar horse in the underworld.Sagara’s sacrificial horse ends up at Kapila’s ashram which becomes the sea when flooded by the Ganga. The horses drawing the chariots of Krishna and Arjuna are special too like those of Achilles and Cuchulainn. A little-known myth in the “Ashvashastra” states that horses were originally winged, like the Greek Pegasus, and Indra, envious of their power, had the sage Shalihotra cut off their wings. The Ramayana has a similar myth about Indra cutting off the wings of flying mountains. Like Buddha’s horse Kanthaka and Pabuji’s magical black mare Kesar Kalmi, we have Rustam’s horse Rakhsh, Hussain’s Zuljenah (celebrated by Shias alone), Buraq that carried the Prophet to heaven, and Roland’s Veillantif. In historical times there is Rani Lakshmi Bai’s Baadal. Strangely enough, despite all the knight-errantry, the Arthurian cycle does not provide a special horse for its hero. Puzzling is Doniger’s statement that in India Karbala may represent the persecution of Muslims not only by Sunnis but by Hindus also with Zuljenah possibly shedding tears for them too (p. 133). Besides the Marathi Khandoba (Shiva mounted a horse to kill the demons Mani and Malla), there are Muslim equestrian saints like Alam Sayyid of Baroda (“Ghore ka pir”) and Satyapir and Dharma Thakur in Bengal to whom Hindus offer clay horses. Doniger overlooks the unique giraffe-necked terracotta Bankura horse that is the motto of the Cottage Industries of India.

In an inspired insight, Doniger points out that the only deity to ride a horse is Kalki (from ‘kalka’, filth of the Kali Era). He is simultaneously the invading barbarian on horseback and the Indian horseman repelling the foreigners, “fighting horses with horses”. She overlooks the fact that Kalki is not a deity but an avatar and none of the avatars, unlike the devas and devis, have “vahanas” (mounts).

Historically, Ashoka is the first ruler to depict a stallion on his lion pillar at Sarnath, and the Buddhist Jatakas describe horse dealers from the north bringing horses to Varanasi. Sindh horses were particularly prized. Horses possibly came late into eastern and north-eastern India where serpent worship prevailed. That is why it is surprising to find in the first Bengali Mahabharata composed by Kavi Sanjaya (c. early 15th century) entire chapters devoted to descriptions of horses of every possible colour.

The horse was brought to India by Arabs by sea and overland by Turks and Mughals. Polo was possibly introduced by the Turks. The Chalukya monarch Someshvara has an entire chapter on it in his “Manasollasa” (12th c. CE). Akbar had “balls of fire” for playing at night according to Abul Fazl. Horses were imported in vast numbers from the Middle East and Central Asia and Arab horses were prizes gifted by the Tughlaqs and Moghuls. In time, horses of Punjab, Rajasthan and even Bengal (called “tanghan” breed) were regarded as the best, with those from Kutch equalling the Arabs. Doniger corrects the misconception that stirrups and horseshoes were introduced to the Delhi Sultanate by Persians and Central Asian Truks in the 12th century as these are seen in sculptures from the 1st century BCE in Sanchi and in c. 950 CE at Khajuraho. The most skilled equestrians were, of course, the Rajputs and their ballads (Pabuji, Devnarayan, Desingh, Gugga) replace epic chariot warriors by mare-riding heroes, often with a Muslim side-kick like Muttal Ravuttan, paralleled by the American Lone Ranger with his Red Indian companion Tonto. But there is also the Telegu Palnadu epic recording the bloody cruelty perpetrated on a recalcitrant colt by Pedanna to tame it. In Tamil Nadu giant figures of horses are dedicated to Aiyanar and there is even a horse-temple known as the Gauripulla Thevar Kovil temple with a brick horse thirty feet long and thirty-five feet high. Tribal myths recount the world as populated with horses first who trample the first human couple till a dog is created to keep them at bay.

The British assigned the failure of Indians to breed good horses to the absence of a caste of breeders and the wrong type of diet, including a lot of ghee, fed to them. The British invented the concept of the thoroughbred from three Arab horses they brought to England. In general Indians did not ride horses, but Doniger overlooks the District Collectors who toured on horseback. Doniger discusses in detail the writings about horses of the father-son duo of the Kiplings. She devotes a full chapter to horses in modern India covering M.F. Husain’s paintings, especially the 12 panel mural, “Lightning” and the breeding of Manipuri polo ponies and Marwari horses who feature in Hollywood and Indian movies.

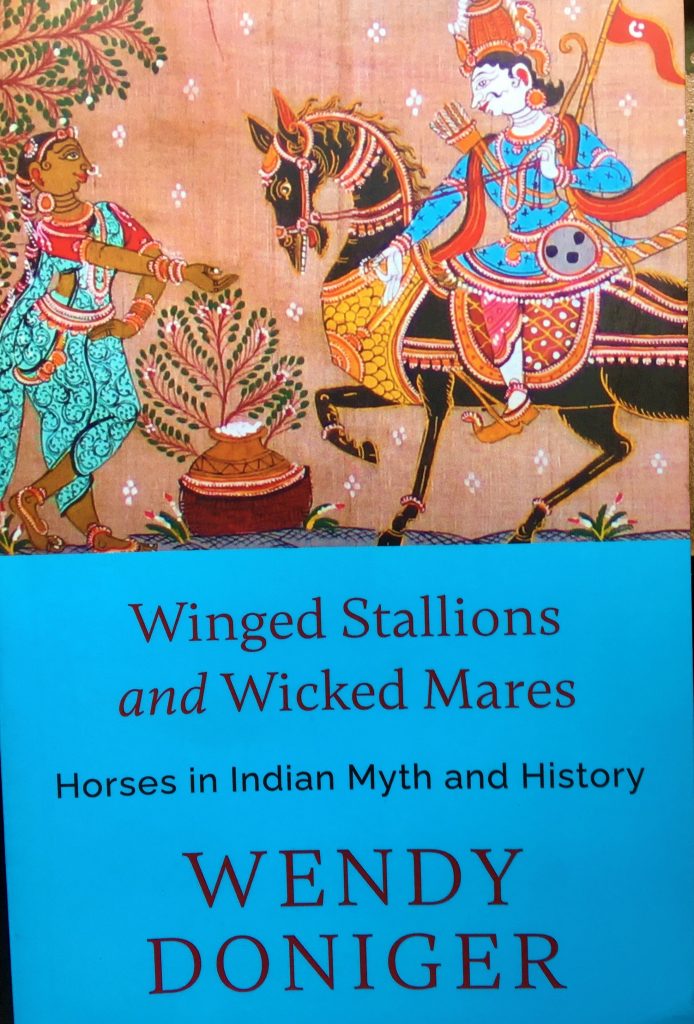

The very attractive front and back covers carry reproductions of warriors astride fully accoutred steeds, white on black and black on white in full colour, complemented by a beautiful picture of the author petting a jet-black horse, possibly in a Pune stud farm. What one misses is a picture of the memorial to the most famous horse in Indian history, Rana Pratap’s Chetak. The printing is excellent and easy on the eyes with hardly any typographical errors. However, in the bibliography on p. 297 the reference to her book “On Hinduism” is printed as pp.473-74 of instead of pp. 473-87 and in note 29 on p. 263 “Hyksos” is misspelt as “Hyskos”. There is also an unsubstantiated claim that at Fort Chunar tales are told about a “Gun Major” which is a British variant of the name Janamejaya (p. 60).

Pradip Bhattacharya retired as Additional Chief Secretary, West Bengal and specialises in comparative mythology.