The parable of the Kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree, narrated by Sri Ramakrishna.[1]

আয়ে মন বেড়াতে যাবি

কালী কল্পতরুতলে গিয়া

চারি ফল কুড়ায়ে খাবি—রামপ্রসাদ সেন

“Come my mind to go a-roaming.

Going to Kālī the Wish-Fulfilling-Tree

Pick up and eat four fruits.”—Ramaprasad Sen (mid-18th century, West Bengal)

Into a room full of children at play walks the proverbial uncle, back from the city, who, of course, knows better. Laughing at their preoccupation with make-believe games, he asks them to lift up their eyes and go out to the massive banyan tree, which will grant them whatever they wish—the real stuff! The children do not believe him and remain busy with their toys. The uncle shrugs and leaves. And then they rush out, stand under the branches of this huge tree that cover the sky and ask for what all children crave: toys and sweets. In a flash they get what they want, but along with an unexpected bonus: the built-in opposite of what they wished for. With toys they get boredom; with sweets tummy-ache. Sure that something has gone wrong with their wishing, the children ask for bigger toys and sweeter sweets. The tree grants them their wishes and along with them bigger boredom and bigger tummy-ache. Time passes. They are now young men and women and their wishes change, for they know more. They ask for wealth, power, fame, sexual pleasure—and they get these, but also cupidity, insomnia, anxiety, and frustration/disease. Time passes. The wishers are now old and gather in three groups under the all-encompassing branches. The first group exclaims, “All this is an illusion!” Fools, they have learnt nothing. The second group says, “We are wiser and will wish better next time.” Greater fools, they have learnt less than nothing. The third group, disgusted with everything, decides to cop out and asks for death. They are the most foolish of all. The tree grants them their desire and, with it, its opposite: rebirth, under the same tree. For, where can one be born, or reborn, but within this cosmos!

All this while one child has been unable to move out of the room. Being lame, he was pushed down in the scramble and when he dragged himself to the window, he was transfixed watching his friends make their wishes, get them with their built-in opposites and suffer, yet compulsively continue to make more wishes. Riveted by this utterly engrossing lila of desire and its fruits, a profound swell of compassion welled up in the heart of this lame child, reaching out to his companions. In that process, he forgot to wish for anything for himself. In that moment of spontaneous compassion for others, he sliced through the roots of the cosmic tree with the sword of non-attachment, of nishkama karma. He is the liberated one, the mukta purusha.

In Anti-Memoirs Andre Malraux writes that in Varanasi an Indian suddenly came up to him and said, “Mr. Malraux Sahib, would you like to listen to a story?” Taken aback, Malraux muttered that he was going to an official meeting. “But this is a very good story,” was the insistent reply. Malraux, perforce, agreed and here is the story he heard:

Narada, the itinerant divine sage roaming the three worlds, sowing seeds of discord and inveterate experimenter, goes up to Vishnu and demands that Maya be explained to him. Vishnu is silent. Narada is not one to be denied. He insists so persistently that the god has to answer him. “Maya cannot be explained, it has to be experienced,” he says. “If you can’t explain what you create, then I won’t believe in you,” retorts the never-say-die sage. Quickly deserting his serpent couch—for the fate of gods in whom humans do not believe is shrouded in uncertainty–Vishnu beckons him to follow. Walking together, they reach a desert where Vishnu sits down under a tree and exclaims, “I am so tired, Narada! Take this lota and get me some water from that oasis. When you return I will explain Maya to you.” Eager to plumb the mystery, Narada speeds off to the oasis and finds a well there beside a hut. He calls out, and a lovely girl opens the door. Looking into her eyes, Narada is reminded of the compelling eyes of Vishnu. She invites him in and disappears indoors. Her parents come out and greet the guest, requesting him to rest and eat after his journey through the burning sands before he returns with the lota of water. Thinking of the lovely girl, Narada agrees. Night falls, and they urge him to leave in the cool morning. Awakening in the morning, Narada looks out and sees the girl bathing beside the well. He forgets about the lota of water. He stays on. The parents offer him their daughter’s hand in marriage. Narada accepts, and settles down here. Children arrive; the parents-in-law die; Narada inherits the property. 12 years go by. Suddenly the floods arrive–floods in the desert! —His house is washed away. His wife is swept away. Reaching out to clutch her, he loses hold of his children who disappear in the waters. Narada is submerged in the floods and loses consciousness. Narada awakens, his head pillowed in someone’s lap. Opening his eyes he gazes into the eyes of Vishnu, seated at the desert’s edge under that same tree, those eyes that remind him of his wife’s. “Narada,” asks Vishnu, “where is the lota of water?” Narada asked, “You mean, all that happened to me did not happen to me?” Vishnu smiled his enigmatic smile. [2]

The Drop of Honey

After the Kurukshetra holocaust, when the blind Dhritarashtra bewails the unjustified misery thrust upon him and turns to Vidura for consolation, this son of Vyasa and a maidservant narrates a gripping parable that provides yet another clue to understanding our existential situation[3]:

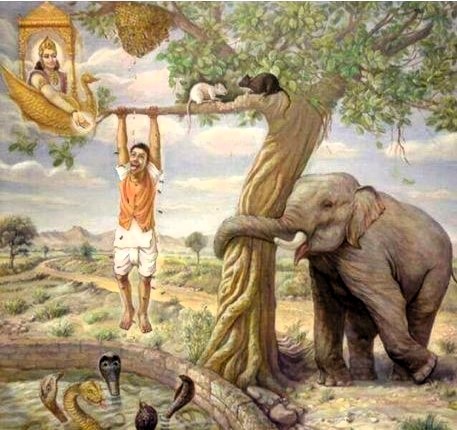

Take a certain Brahmin who loses himself in a dense jungle filled with wild beasts. Lions and tigers, elephants and bears…Yelling and trumpeting and roaring…a dismal scene to frighten even the god of death, Yama. The Brahmin is terror-stricken. He horripilates. His mind is a bundle of fears. He begins to run, helter-skelter; he looks right and left, hoping to find someone who will save him. But the fierce beasts—they are everywhere—the jungle echoes with their weird roaring—wherever he goes, they are there, ahead of him.

Suddenly he notices that the fearful forest is swathed in a massive net. In front of him, with open arms, is a horrendous-looking female. Also, five-headed snakes hiss at him—tall snakes, their hill-huge bodies slithering up to the sky.

In the middle of the forest is a well covered with grass and intertwining creepers. He falls in that well and dangles there, clutched by a creeper, like a jackfruit ripe for plucking. He hangs there, feet up, head down.

Horror upon horror! In the bottom of the well he sees a monstrous snake. On the edge of the well is a huge black elephant with six heads and twelve feet hovering at the well’s mouth. And, buzzing in and out of the clutch of creepers, are giant, repulsive bees surrounding a honeycomb. They are trying to sip the deliciously sweet honey, the honey all creatures love, the honey whose real taste only children know.

The honey drips out of the comb, and the honey drops fall on the hanging Brahmin’s tongue. Helpless he dangles, relishing the honey drops. The more the drops fall, the greater his pleasure. But his thirst is not quenched. More! Still more! ‘I am alive!’ he says, ‘I am enjoying life!’

Even as he says this, black and white rats are gnawing the roots of the creeper. Fears encircle him. Fear of the carnivores, fear of the fierce female, fear of the monstrous snake, fear of the giant elephant, fear of the rat-devoured creeper about to snap, fear of the large buzzing bees…In that flux and flow of fear he dangles, hanging on to hope, craving the honey, surviving in the jungle of samsara.

The jungle is the universe; the dark area around the well is an individual life span. The wild beasts are diseases. The fierce female is decay. The well is the material world. The huge snake at the bottom of the well is Kala, all-consuming time, the ultimate and unquestioned annihilator. The clutch of the creeper from which the man dangles is the self-preserving life-instinct found in all creatures. The six-headed elephant trampling the tree at the well’s mouth is the Year—six faces, six seasons; twelve feet, twelve months. The rats nibbling at the creeper are day and night gnawing at the life span of all creatures. The bees are desires. The drops of honey are pleasures that come from desires indulged. They are the rasa of Kama, the juice of the senses in which all men drown.

This is the way the wise interpret the wheel of life; this is way they escape the chakra of life.

Dhritarashtra, of course, misses the point Vidura is making: man, literally hanging on to life by a thread and enveloped in multitudinous fears, is yet engrossed in the drops of honey, exclaiming, “More! Still more! I am alive! I am enjoying life!” And, like the blind king, we tend to miss the point too. Ignoring the law of karma, taking that other road, we fall into the pit and rale; but inveterately, compulsively, perversely, strain every sinew to lick the honey.

The Buddha figured it forth in a characteristically pungent image:

Craving is like a creeper,

it strangles the fool.

He bounds like a monkey, from one birth to another,

looking for fruit.[4]

If heeded, the doctrine of karma becomes a powerful instrument for building character, maintaining integrity and establishing a society that functions not on matsya nyaya [the big devouring the small] that celebrates individualism, but on dharma that upholds society and the world itself.

Determination & Free will

The whole point of comprehending this doctrine lies in perceiving that the much-vexed controversy over determination and free will is resolved if seen in perspective. Let us, once again, take recourse to a story to understand this complicated issue.[5]

Two friends, Shyam and Yadu, lived in a village. Shyam was an ambitious go-getter, and Yadu a happy-go-lucky, ne’er do well. Keen to know the future, they approached a hermit who lived apart in the forest. After much persuasion, he agreed to look into the future and tell them their fates. After a year, he said, Shyam would become a king, while Yadu would die. Returning to the village, the shocked Yadu turned to prayer and began leading an exemplary life. Shyam, immediately on reaching the village, started throwing his weight about, grabbing whatever he fancied from others, threatening anyone who dared to protest, vociferously announcing that soon he would be their king.

A year passed by. Shyam sought out his friend and asked him to help pick the site for his palace. As they walked along the river bank, Shyam stumbled over something and fell. Picking himself up, he found the mouth of a jar protruding from the sand. Digging it up, he found it full of golden coins. Hearing his shouts of celebration at finding such treasure, a robber ran up and tried to snatch the jar. Yadu rushed to Shyam’s help and clutched on desperately to the robber’s leg. Unable to tackle the joint resistance of both friends, the infuriated robber stabbed Yadu on his arm and ran off.

Days passed. Yadu did not die; Shyam found himself still no king. So, they went off to the forest and hunted out the hermit. Confronting him, they demanded an explanation for the failure of his prophecy. The hermit went into meditation and then explained: the conduct of each of them had altered what was fated. Yadu’s austerity and prayers had reduced the mortal blow into a stab injury. Shyam’s tyrannical conduct had reduced the king’s crown to a jar of gold coins.

Fate, therefore, is altered by the individual’s choice of the path. Those that have eyes can see; those that have ears can hear. To develop this intuitive sense one has to dive deep, beyond the superficial sensory perception to the manas and cultivate living in that peace within, that pearl beyond price.

[1] Pradip Bhattacharya: “Desire under the Kalpataru,” Jl. of South Asian Literature, XXVIII, 1 & 2, 1993, pp.315-35 & cf. P. Lal’s Introduction to Barbara Harrison’s Learning About India (1977).

[2] P.Lal: Valedictory Address in Mahabharata Revisited (Sahitya Akademi, 1990, p.291-302–papers presented at the international seminar on the Mahabharata organized by the Sahitya Akademi in New Delhi in February 1987).

[3] P. Lal: The Mahabharata (condensed & transcreated, Vikas Publishing House, New Delhi, 1980, p. 286-7)

[4] P. Lal: The Dhammapada, op.cit. p.157.

[5] Related by Prof. Manoj Das in an address at Sri Aurobindo Bhavan, Calcutta, in 2000