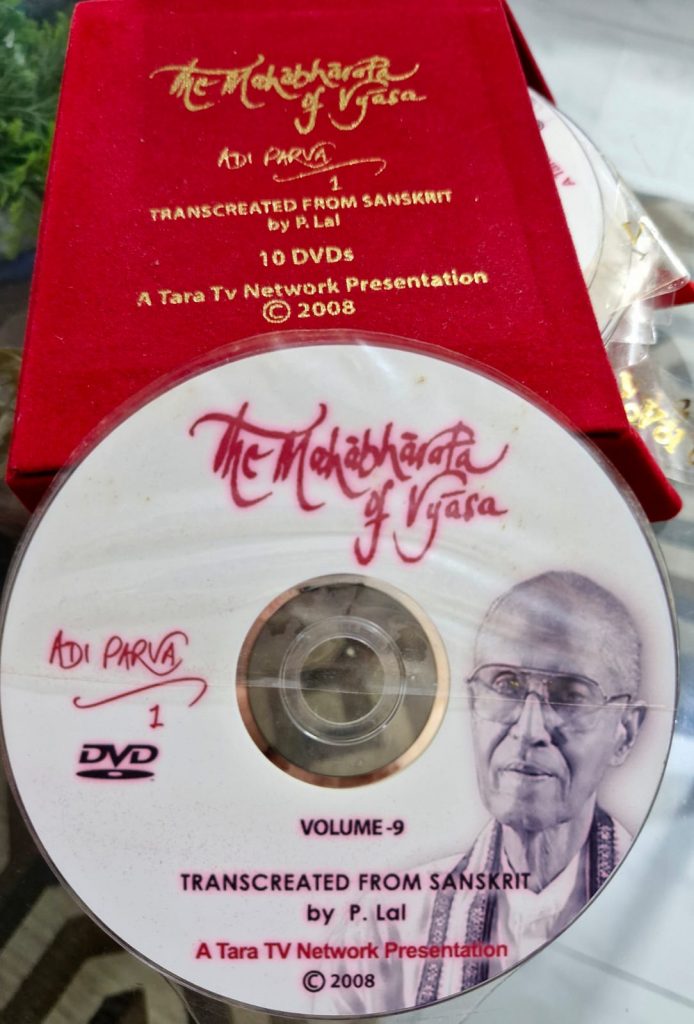

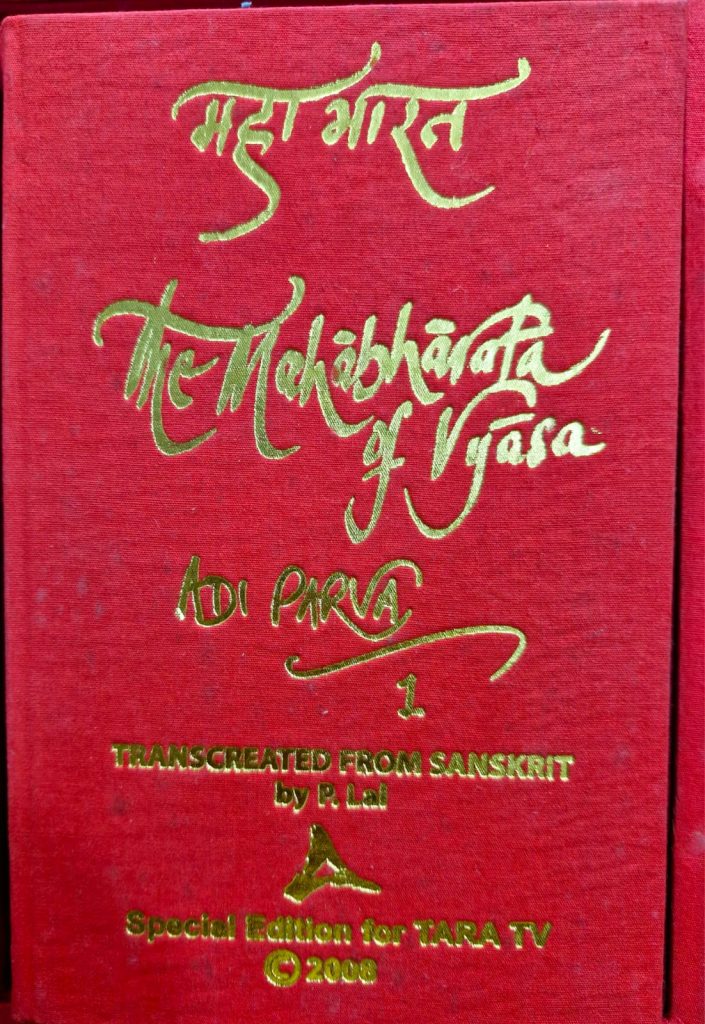

P. Lal: The Mahabharata of Vyasa, Adi Parva-1, transcreated from Sanskrit, Tara TV, 10 DVDs + printed volume.

The 50th anniversary of Writers Workshop was celebrated in Kolkata in early 2009 with the Governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi releasing the first instalment of Tara TV’s production of Padma Sri and Nehru Fellow Professor P. Lal’s recitation of his Mahabharata transcreation. These ten DVDs are unique. There are no other recordings of Vyasa’s monumental work in English, verse-by-verse. The packaging in a red box with the title embossed in gold in P. Lal’s signature calligraphy is a connoisseur’s delight. The discs carry an excellent photograph of the transcreator and are complemented by the printed text in a hardbound, gold-embossed edition.

The epic journey of the Lal transcreation began towards the end of 1968 taking the form of monthly fascicules. From 2005 he published extensively revised editions, each parva in a single volume. Now 16 ½ of the 18 parvas are in print, except for the Mokshadharma part of the Shanti and the Anushasana—the only modern English version to have gone that far.[i] Only K.M. Ganguli and M.N Dutt had complete prose translations in the late 1890s, but both omitted portions of the text. This is the only transcreation that incorporates what the Bhandarkar Critical Edition has omitted, and is also the only one to follow faithfully the original’s verse and prose formats (all others are only in prose). That is where Prof. Lal’s poetic genius lends a unique flavour to this version. Those who have read his monthly fascicules will be mistaken if they give this recording a miss. The spoken introduction is a new and brilliant overview of the key issues in the Mahabharata, unique as much for its insights as its style. The Professor is, after all, at his best delivering a lecture. It is spiced with inimitable touches of punning sarcasm (“The battle of Kurukshetra— call it genocide, parricide, gurucide, suicide— whatever; such brotherly butchery!” Or, “The fathering of Yudhishthira by Vidura is one of the best kept open secrets”). One turns to the accompanying volume to savour the rich feast of insights, only to find it missing.

Vyasa begins, Prof. Lal points out, with an amazingly pompous claim to have all the answers: “What is here may be elsewhere; what is not here is nowhere else.” All scriptures and shastras were weighed against it and Mahabharata tipped the scale, “heavier than all the respected heavies. As it had more “bhaara” it was known as Bhaarata.” But another meaning of the word the prince of transcreators overlooks is “war” (cf. Bhasa’s Karnabhara). Akbar knew this. When he commissioned the Persian adaptation in 1582, he named it Razm Nama, the Book of War.

Perhaps because of such multiple layers of meaning Vyasa insisted that Ganesha understand each word before writing it down. “For what is the point of listening without understanding and assimilating? The language enshrines ideas and values; the style is only the tool. What matters is the meaning.” Should we chase money or the meaning of money (artha); lust or love (kama); ritual or spirituality (dharma); escape from life or transcend it (moksha)? For Prof. Lal, Vyasa’s one message is: transform yourself—transform money into the meaning of money; lust into love; ritual into spiritual; escape into transcendence. But, as Krishna-Narayana (divinity in humanity), tells Arjuna-Nara (humanity in divinity), “You are free to choose.” Why does pacifist Arjuna turn militarist? Why does Yudhishthira not refuse to lie? Why does Bhima hit below the belt? Why does Arjuna kill Bhishma and Karna unfairly? Why does Nara take the ignoble way to victory?

The clue lies right in front, as in the best detective stories, and we fail to see it. Prof. Lal points to the first word in the opening invocation: “Narayana” who is Krishna, the crux of the Mahabharata, without whom it is Shakespeare’s Hamlet without the prince of Denmark. It is all about “wonder-working war” in which Krishna, the omniscient hero, is present but will not fight. Narayana knows the best route to travel, but will not drive until we, Nara, tell him where to take us. Yet, the first Arabic summary of the epic by Abu-Saleh in 1026 AD is astonishingly innocent of this presence. Is Krishna’s role in the war a later interpolation?

After the war Vidura, having tried to console Dhritarashtra with the story of the man in the well (that became the biblical “Barlaam and Josaphat”) teaches Yudhishthira a lesson when he wishes to commit suicide by suggesting that he first find out what is common to river, tree, earth and woman. Slice a river and it flows on, fertilising the land; cut a branch and new shoots sprout; plough the land and it produces food; exploit a woman and she gives progeny and ensures the continuity of civilization—all without blame or revenge. Physical suffering is transformed into fruitful creativity. “Learn! Vyasa urges. Learn from my life how to live as a human being should, otherwise calamity awaits you and all around you. Utthishtha, stand up, wake up, learn and charaiveti, keep moving. No regret, no blame, only transformation of pain and suffering into creativity and progress.” Yet, at the end why does Vyasa shout with arms uplifted, “From dharma come wealth and pleasure. Why, is dharma not practised?” Hastinapura is entrusted to Yuyutsu, begotten by Dhritarashtra on a maid, as the regent; Indraprastha is left to the Yadava Vajra, Krishna’s great grandson.

The entire epic is a flashback a century since the war. Janamejaya wants to know about his family tree, its roots, shoots and fruits, whether sweet or bitter. How else can he know himself—for he is the latest leaf on that tree. And so his ancestor Vyasa narrates his story which is also the history, itihasa, of a country, the chronicle of one family, a symbolic universal drama of mankind slowly evolving through dissension and war to self-knowledge and peace— hopefully.

Dictated to Ganesha and recited to Janamejaya, that oral and aural experience is sought to be conveyed to an English-knowing audience, keeping the Indian flavour intact. Aficionados of Vyasa will be grateful to Tara TV for this signal contribution. The advantage is that the ear catches what the eye has missed in print. In section 63, verse 102 the translation erroneously has Kunti emerging from a yajna-fire having misread” jajne” (“beget”; Surya and Kunti beget Karna) for “yajne” (“from yajna”). Prof. Lal’s is the only English version that sensitively shifts from verse to prose and vice-versa, following the complete “vulgate” shloka-by-shloka. The disks cover the introduction (memorable for Dhritarashtra’s plangent lament), the list of contents, the chapters on Paushya, Puloma, Astika (including the archetypal churning of the ocean, the wondrous story of Garuda and the snake sacrifice), the partial incarnations (including Vyasa’s birth and the war summarised). It cuts off abruptly at verse 21 of section 66 of the Sambhava parva. A bookmark would have been helpful to mark the page where a disk ends instead of having to hunt through the 264 pages every time. Do not look for colophons, chapter headings, annotations, glossaries, list of contents. The rhapsode does not need them.

We thrill to the evocative verses describing Creation transcreated with biblical resonance:

“At first, there was no light,

no radiance, only darkness;

then was born the egg of Brahma,

exhaustless and mighty seed of life…

from which flow being and non-being.”

Or savour the lovely description of Meru, evoking profound archetypal memories within us:

“There is a mountain called Meru,

a flaming heap

of splendour.

Sunlight falls on it

and scatters

at the summit.

It is golden: it glitters:

It cannot be measured:…

Mind cannot

conceive of it.”

Pradip Bhattacharya, International HRD Fellow (Manchester), retired as Additional Chief Secretary, West Bengal. His PhD is on the Mahabharata.

[i] My translations of the Mokshadharma part of the Shanti Parva and the complete Anushasana Parva have been published by Writers Workshop.