Neera Misra, Rajesh Lal ed.: Indraprastha Revisited, B.R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi, 2017, pp. 264

The Draupadi Dream Trust founded and chaired by Smt. Neera Misra of Kampilya—Panchali’s birthplace—organized the first Indraprastha Festival in November 2016 to highlight the need for recovering and showcasing evidence of this millennia old city. Besides a performance of the Indonesian “Wayang Kulit” depicting how Indraprastha was built according to the legend in Bali, an international conference was held covering a variety of topics centred on Indraprastha. 23 of these papers have been published in this large format volume along with a host of sketches and plates that make it an important book for anyone interested in the heritage of ancient India.

There are several papers by eminent archaeologists led by their doyen Dr B.B. Lal who was the first to locate and excavate both Hastinapur (in Meerut district) and Indraprastha (in Purana Quila) 60 years back. Unfortunately, since then only desultory digging has taken place. So far nothing earlier than Painted Grey Ware pottery (around 1000 BCE) has been found at sites associated with the Mahabharata. It is puzzling why there is no reference to Dr. Gauri Lad’s thesis on the archaeology of the Mahabharata for which the renowned Dr. H.D. Sankali was the guide.

However, J.N. Ravi’s extremely valuable study of Balarama’s pilgrimage along the Sarasvati reveals the links that would have existed between Harappan culture along this river (e.g. Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana dated around 3000 to 2000 BCE), Hastinapur on the Yamuna and Indraprastha on the Ganga. That is why it is puzzling why no excavation has been carried out at Kurukshetra, the site of the bloodiest of all carnages where eleven armies were decimated. Surely some metal artefacts ought to turn up if there is any historical basis to the “itihasa”. Ravi’s paper unaccountably omits the tirthas named after the Vriddhakanya (old woman) who could attained Swarga only after marrying and the Kanya who went to heaven remaining a virgin throughout. The latter half of his paper is an excursion in Euhemerism with Yayati’s sons migrating to become Danaans, the Irish (Danavas), Avestans (Daityas), only missing out on linking Ila with Elam in ancient Iran! Acharya Chatursen had presented a far more evocative picture in his great Hindi novel, Vayam Rakshamah.

“Archaeo-astronomy” is a new term coined by those dating the Mahabharata war by using astronomical data from the text. This book exposes the mutually contradictory dates arrived at. Narhari Achar fixes it in 3067 BCE, along with precise dates for Draupadi’s birth, marriage and the lacquer house episode. As the editors have not provided the bibliography for his paper, the references cannot be verified. A.K. Bhatnagar decides upon 14 October 1793 BCE for the start of the war, besides fixing dates for Varanavat, Krishna’s embassy, the deaths of Bhishma, Drona, Karna and Duryodhan. Besides interpreting the same data differently, Koenraad Elst favours post-1900 BCE because the Sarasvati “must have” (?) dried up around that time and as S.R. Rao dates Dwarka to 1700-1500 BCE. They are all unaware of Dr. Sita Nath Pradhan’s research finding that the war occurred in 1150 BCE. Clearly, no firm date upon which twelve good people and true agree can emerge!

A.D. Mathur draws only upon the Shanti Parva for the principles of governance instead of linking it to what is found elsewhere, e.g. the Machiavellian advice Kunika tenders to Dhritarashtra for getting rid of the Pandavas, or the questions Narada puts to Yudhishthira at Indraprastha. Come Carpentier skips all over the immense span of comparative mythology, compares Indraprastha to Angkor and can come to no conclusion about the historicity of the city. In asserting the existence of copper weapons for the war he is mistaken as no such weapons have been found in any site of that antiquity in this region. Shashi Tiwari’s account of Kaliyuga dynasties with reference to Indraprastha is disappointing as it merely paraphrases Pargiter’s research instead of looking at the different findings of Sita Nath Pradhan in his Chronology of Ancient India (1927) and Kunwar Lal Jain’s Chronology of India in the Puranas (1993). She even mis-attributes a list of puranas to the Mahabharata. She assigns the last date for them to 7th century AD whereas the Bhavishya Purana includes references to the British, the Brahmavaivarta Purana is of the 16th century and the Linga and Shiva Puranas are 10th to 11th century. The most flagrant error is her assertion that Yudhishthira’s line ruled in Indraprastha whereas it is Arjuna’s dynasty that ruled in Hastinapura while Krishna’s great grandson Vajra (and his descendants?) ruled in Indraprastha. What the Kurukshetra War achieved was the establishment of the hegemony of the Yadavas in the heartland of Northern India. The bloodline of Puru/Kuru died with celibate Bhishma. Actually, even Kuru is not a Bharata by blood because King Bharata disinherited all his sons, adopted the Brahmin Bharadvaja re-naming him Vitatha and put him on the throne. It is this Brahmin’s lineage that ends with Bhishma.

There is an important paper by Chahan and Pachauri on the role NGOs and citizens can play in preserving and promoting our cultural heritage. This deserves wide dissemination for implementation. Renu Khanna contributes an architect’s vision with pictures on showcasing Indraprastha as a tourist destination. She refers to having studied “the detailed English illustration of the Mahabharata” which does not exist. The editors should have corrected this to “translation” and provided the reference.

Swapna Liddle’s paper is a valuable presentation of how local builders introduced traditional Hindu motifs even while constructing Muslim edifices, e.g. the Kirtimukha, the lotus and the water pot but did not adopt the true arch till 1280 (cf. Balban’s tomb). She shows a picture of the invocation to Vishvakarma and the name of the Hindu architect inscribed on the Qutub Minar. Unfortunately these fascinating aspects are not highlighted in the ASI plaques, although these provide excellent instances of communal harmony. Sudha Satyawadi contributes an illuminating paper on art and architecture in the Janapada period while Arundhati Dasgupta summarises how modern art depicts the Mahabharata. Rupali Yadav describes the dice-game scene in a mural of the Chattar Mahal of Kota Palace, Rajasthan. Unfortunately, the plate only shows the full mural with no enlargement showing the detail of Duryodhana consulting an astrologer. The editors should have ensured this.

Somnath Chakraverty writes on the ethnography of the epic. He draws upon B.S. Upadhyaya and H.D. Sankalia without citing the references and asserts that names of nagas are drawn from Assyrian kings and therefore they came from that region. Without citing any evidence he asserts that the Yadavas were from Western Asia and Iran. He also says that “there are enormous evidences” from Indus towns of serpent worship, again without supporting reference. It is disconcerting to find him claiming that rock art at Bhimbetka and elsewhere records “mass genocide and battle” that is replicated throughout India. While he states that these belong at least to the Gupta period if not earlier, actually rock art is dated much earlier (10,000 BCE at Bhimbetka).

Major General G.D. Bakshi’s paper on the geo-politics of that time is a superb analysis showing that the autocratic royalty banded together to crush the nascent “democratic” (actually oligarchic) government of the Yadavas. Krishna kept the Yadavas out of the war so that when the field was swept clear, they could take over Indraprastha under Krishna’s great grandson Vajra. Kritavarma’s son and the Bhoja women were given Marttikavat (unknown) while Satyaki’s son was settled on the banks of the Sarasvati, both nearby. K.T.S. Sarao’s very interesting paper describes little known data from Buddhist sources regarding Indraprastha, e.g. that Buddha’s razor and needle were deposited there and its ruler was Dhananjaya Koravya of the Yudhitthila gotra.

Several of the contributors make the common error—not expected from Indologists—of asserting that initially the Mahabharata consisted of only 8,800 verses. This is the number of riddling, knotty slokas Vyasa composed to gain time to compose more while Ganesh scratched his head trying to understand them. The “Jaya” version was 24,000 slokas without ancillary tales, which Vyasa expanded to several lakhs of which one lakh verses were recited to Janamejaya by Vaishampayana in his guru’s presence during the snake-sacrifice in Takshasila.

Neera Misra’s paper presents an overview of the archaeological and other data on the subject, most of which has been featured in individual papers. Hers is a fervent plea for opening up the Purana Quila site for displaying the excavations which ought to be taken further and making it a tourist destination. The editors should have added a line or two about each contributor instead of merely providing their e-mail addresses. The large number of colour plates and sketches of archaeological finds, maps and paintings make this volume a collector’s item. Hopefully the publication will stimulate excavations in key sites mentioned in the Mahabharata and lead to the setting up of a Mahabharata tourist circuit.

Pradip Bhattacharya

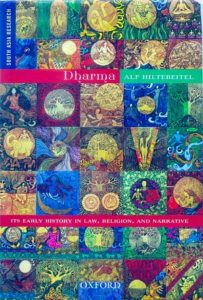

Alf Hiltebeitel: Dharma: Its early history in law, religion and narrative

Alf Hiltebeitel: Dharma: Its early history in law, religion and narrative