Devdutt Pattanaik: Jaya, Penguin, 350 pages, Rs. 499/-.

How shall vibrant shoots of the future come forth unless we go to our roots? That is why Janamejaya, king of Hastinapura, requests Vyasa, his ancestor, to tell him about his lineage. Retellings of Indian mythology have been many but for the first time we have a medical doctor ministering to the spirit by evoking archetypal memories through his retellings. Of his work, the most significant is this attempt to re-tell the Mahabharata in a new way.

How shall vibrant shoots of the future come forth unless we go to our roots? That is why Janamejaya, king of Hastinapura, requests Vyasa, his ancestor, to tell him about his lineage. Retellings of Indian mythology have been many but for the first time we have a medical doctor ministering to the spirit by evoking archetypal memories through his retellings. Of his work, the most significant is this attempt to re-tell the Mahabharata in a new way.

A.K. Ramanujam spoke of 300 Ramayanas—and was taken off the Delhi University syllabus for it. There are possibly as many Mahabharatas; each of our languages with its own version, besides the Indonesian and Malayan. Retellings of it are legion, from 12-year old Samhita Arni’s to economist Bibek Deb Roy’s, but none includes glimpses of regional variations like this one which, hopefully, will not attract the ire of fundamentalists. For instance, for the horse-sacrifice; Pattanaik—like Akbar in1592 for the Razm Nama and the Bengali and Assamese Mahabharatas—follows the composition of Vyasa’s pupil Jaimini. Sensitively split into 18 chapters like the original, with a prologue and an epilogue, each has a bulleted addendum in a grey box—management manual style—providing insights, commentary and additional information. Lest the “maha”-ness of the work put off the modern reader, the style is kept simple, unpretentious and focused on communicating the significant events clearly (though calling Shiva “the great hermit” is awkward, as is “the father of the planet Mercury is the planet Jupiter”). Fine sketches by the author (assisted by his chauffer), and an attractive, reader-friendly layout enliven the read. His interpretation of the difference between “vijaya” and “jaya” is meaningful indeed: the former connotes victory over others; the latter is spiritual conquest of oneself.

A few omissions detract from the retelling’s dramatic effect, e.g. Keechak chasing Draupadi into Virat’s court and kicking her before Yudhishthir and Bhim. More important is the absence of the overarching themes that are so crucial to Vyas’ weltanschauung: Time, Desire and its fruits, the eidetic image of the cosmic tree that occurs in the Shanti Parva and the Gita. And what about the Bharata-Savitri, that unforgettable anguished cry with which Vyasa ends his great epic, asking a question which remains as pertinent today as millennia ago: “From dharma flow wealth and pleasure. Then why is dharma not practised?”

While making this very commendable effort to reach the world’s longest epic to today’s reader whose attention span is so short, misleading distortions of fact could have been avoided. Vyas’ Shakuntala is not Kalidas’ love-smitten teenager who promptly succumbs to Dushyant’s blandishments, as Pattanaik retells. She first gets him to promise that their son will inherit the throne. For the story of Chitrangada Pattanaik abandons Vyas for Rabindranath. There are departures from the original without any indication of the source for such a different account, e.g. the gods, instead of Shantanu as in Vyas, decree that Bhishma will be able to choose the time of his death. And when was he ever engaged to marry the Kashi king’s sister? It is Pandu, not Kunti, who speaks of women in olden times being promiscuous yet blameless and it is he who worships Indra for a son. Kunti never invokes any god on her own after the fiasco with Surya. All her sons are called “Partha”, not just Arjuna.

Satyavati does not elect to retire to the forest; it is Vyas who asks her to do so as “the green years of the earth are gone/do not be a witness to the suicide of your race.” How is Nanda the brother of Vasudev’s wife Rohini? It is not Balarama’s plough but his pestle (musala) that possibly became Vishnu’s club. Krishna has no role in Dhritarashtra’s giving Khandavprastha to the Pandavas. It is before and not after the burning of the forest that Agni gives Krishna and Arjuna their weapons and chariot, obtaining them from Varuna, which they use in the massacre.

The bard who listens to Vaishampayan’s recital of Vyas’s composition at the snake-sacrifice is not Romaharshan but his son Ugrashrava Sauti, who narrates it to Shaunak (not “Shonak”) and other sages. Shuk narrates it to Parikshit not “as he lay dying”, but while he ekes out the days till he is fated to die.

Bhim’s marriage with Hidimba occurs immediately after the Pandavs escape the house-of-lac, not after the killing of the ogre Bak as Pattanaik has it. Kunti is not uncomfortable with the Hidimba-Bhim marriage; actually, she welcomes it so that the friendless Pandavs obtain allies.

As precedents for Draupadi’s polyandrous marriage Yudhishthira cites Varkshi and Jatila, not Vidula. The Pandavs are not sent to Varanavata at Vidura’s instance to create a safe distance between the cousins, nor does he visit the inflammable dwelling. It is Dhritarashtra who insists the Pandavs go there to celebrate the festival of Shiv. Yudhishthira does not stake Draupadi on his own but only when Shakuni suggests it. The Brihannala-Uttara episode is not just burlesque but anticipates Arjuna’s refusal to fight and Krishna’s exhortations. If Abhimanyu married Balaram’s daughter Vatsala, then what happened to their progeny who and not still-born Parikshit should have been the successor? Parikshit’s revival occurs after the Pandavs return with the treasure of Marutta to perform the horse-sacrifice, not before it.

The account of Parikshit’s resuscitation is disappointingly drab, particularly where the original is so inspiring. Krishna performs an act-of-truth, “If have I turned away from battle; if truth and dharma are ever firm in me; if I am ever devoted to truth and Brahmins; if I have never I quarrelled with my sakha Arjuna; then, by the power of these truths, may Abhimanyu’s dead son live!” Krishna’s miraculously saving the Pandavas from the hungry Durvasa and his disciples occurs after the magical cooking vessel is given by Surya to them, not before as retold. After Ulupi resurrects the dead Arjun, there is no question of his not recognizing her. He thanks her for purifying him of the sin of killing Bhishma by devious means and sends her with Chitrangada and Babhruvahan to Hastinapur for the ashvamedha ceremony after which Yudhishthir loads his nephew with wealth.

Lakshman does not chop off Surpanakha’s breasts, but her nose. It is not Indra but Vishnu who humbles Garuda and prevents him from devouring Sumukha. Drona does not trap Pandava warriors within the wheel formation. They find it impossible to break into it. That is why they cannot follow Abhimanyu who alone knows how to enter it. Arjuna does not slice off Bhurishrava’s arm on his own but only on Krishna insisting he intervene to save the supine Satyaki. At no stage does Krishna shout “Kill him!” about Drona, certainly not after he lays down his weapons. Arjun rushes towards Dhrishtadyumna shouting in vain that he must not kill the guru. Everyone on the battlefield condemns the beheading of meditating Drona.

Pattanaik contradicts himself by writing that Krishna stands before Uttari (sic.) and prevents the unborn child from being harmed by Ashvatthama’s missile, while later he speaks of her delivering a dead child. The Mahabharata does not know of the former incident. Pattanaik attributes Markandeya’s vision of an infant on a banyan tree leaf sucking its toe, afloat on the waters of dissolution, to Arjun. Krishna’s great grandson was Vajra, not Vajranabha, a demon whom Pradyumna killed and married his daughter Prabhavati. After Krishna’s death all the Yadavas were not settled in Mathura by Arjun. He established Vajra in Indraprastha and Satyaki’s son Yauyudhani in the plain of Sarasvati.

There are several misspellings: “Vishaparva”, “Hastinapuri”, “Adiratha”, “Yudhishtira”, “Jayadhrata”, “Uttari”, “Lakshmani”, “Arshitsena”, “Vajranabhi” are not the correct names of Vrishaparva, Hastinapura, Adhiratha, Yudhishthira, Jayadratha, Arshtisena, Uttara, Lakshmana and Vajranabha.

Pattanaik enriches the proceedings by including stories from puranas and regional sources, e.g. Abhimanyu marrying Balaram’s daughter Vatsala with Ghatotkach’s help (made into a landmark film “Maya Bazar”), Krishna’s son Samba marrying Duryodhan’s daughter Lakshmana, Arjun and Krishna confronting each other over Gaya, Arjun and Hanuman at odds. He could have mentioned the Bengali “Dandi Parba” [presented on stage as “Pandab-Bijoy” by Girishchandra Ghosh] in which the Pandavas and Kauravas jointly oppose Krishna who attacks Raja Dandi for possession of a mare that is actually the apsara Urvashi. There is a similar bhakta-vs-bhagavan episode from a regional source regarding Hanuman protecting Raja Shakunt of Kashi from Rama. Krishna reprimanding Draupadi in exile for being responsible for her misery is Pattanaik’s own concoction. However, he provides a new insight by comparing Vikarna and Yuyutsu with Kumbhakarna and Vibhishan. He includes the remarkable tale of Krishna as Mohini marrying Iravan for a night before the Pandavas sacrifice him that is not known outside south India. Sensitively, he includes the fascinating tale of Bhangashvana who experienced life as male and as female and the riveting parable of the drop of honey Vidura tells that found its way into medieval biblical lore as the tale of the man in the well in Barlaam and Joshaphat. Pattanaik concludes on a profound note, evoking the lesson that anrishamsya, non-cruelty, universal compassion, is the secret of a meaningful life.

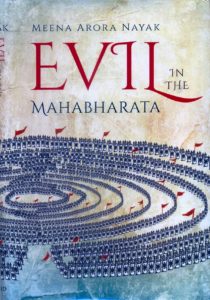

Meena Arora Nayak: Evil in the Mahabharata, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 355, Rs. 650/-

Meena Arora Nayak: Evil in the Mahabharata, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 355, Rs. 650/-

The Condensed Mahabharata of Vyasa by P. Lal, First published 1980, 3rd edn 2010 (Revised and Corrected) Price: HB Rs 600, FB Rs 400

The Condensed Mahabharata of Vyasa by P. Lal, First published 1980, 3rd edn 2010 (Revised and Corrected) Price: HB Rs 600, FB Rs 400