Jaiminiya Mahabharata.

The Lost Mahabharata of Jaimini

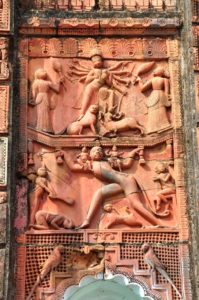

Hanuman rescuing Rama-Lakshmana. Terrocotta panel in Narayanpur in Bankura District

Vyasa had five disciples: Vaishampayana, Jaimini, Paila, Sumantu and his own son, Shuka. In the Adi Parva, section 63 of the Mahabharata, Vaishampayana tells Janamejaya about his guru:-

“He compiled the Vedas.

And was called Vyasa, the Compiler.

Next he taught the four Vedas

And the fifth Veda, the Mahabharata, – 93To Sumantu, Jaimini, Paila,

His own son Shuka, and to me,

His disciple Vaishampayana. – 94And the Bharata Samhita

He published through them

Each separately….[1]

So, Vyasa had these five compose their individual versions. Only the one recited in his presence by Vaishampayana at Janamejaya’s snake sacrifice is extant in full as transmitted by Ugrashrava Sauti to Shaunaka and his sages in the Naimisa forest during intervals of their sacrificial rite. Of Jaimini’s version, only hisAshvamedha Parva exists in full where it is he who recites it to Janamejaya. The legend is that Vyasa rejected all the other compositions. According to Shridhara’s Marathi Pandavapratapa (17th century), Vyasa condemned Jaimini for introducing his own material. [2] This parva is of great significance because when Akbar commissioned Razmnama (Book of War, 1584, the Persian translation of the Mahabharata), for the Book of the Horse Sacrifice he chose Jaimini’s version over his guru Vyasa’s as is evident from the illustrations. We do not know if he made similar choices for the other parvas because his copy has not been studied, being locked away, inaccessible, in the Jaipur Palace museum.

Indications exist in Jaimini’s text that other parvas, preceding and succeeding this fourteenth one, existed. At the end (Section 68, slokas 14-15) Jaimini says,

“O lord of the people, I have narrated fourteen parvas. Now, O king, listen to the parva named Ashramavasa.”

Further, in Section 36, slokas 84-85.5, Suta (not “Sauti” who transmits Vaishampayana’s recital) addresses an audience of ascetics, presumably identical to Shaunaka and his community of sages in Naimisharanya:-

“Suta said, “O bulls among ascetics, I have described to you all that Jaimini had told the son of Pareekshit.”

The way in which the name of Janamejaya’s father is spelt (Pareekshit instead of Parikshit) provides a clue to Jaimini’s period, as this spelling occurs first in the Bhagavata Purana. It means, “to look around,” while the Vyasa version means, “remnant (of a ruined family).”[3] Unfortunately, those other parvas are yet to be found.

The manner in which Jaimini’s Sahasramukharavanacaritam begins, with Janamejaya’s queries following the return of Sita and her sons to Rama, indicates that it is a sequel to Jaimini’s Ashvamedha Parva account of Lava and Kusha’s battle with Rama.

During research for editing the first English translation of the Jaiminiya Ashvamedha Parva, [4] exciting information was received from Professor Satya Chaitanya, visiting faculty at the XLRI Jamshedpur, that Government Oriental Manuscripts Library and Research Centre of the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology had palm-leaf manuscripts in Grantha script ascribed to the lost Jaimini Bharata.

Of 15 manuscripts 2 that were complete, viz. Sahasramukharavanacaritram (The Thousand-Faced-Ravana’s Deeds), and Mairavanacaritam (The Dark Ravana’s Deeds) were critically edited and published with a sloka-by-sloka English translation in free verse by S.K. Sen and myself. Neither has been published previously. The Lava-Kusa manuscript was not included, though complete, as the episode was included in S.K. Sen’s translation of Jaimini’s Ashvamedha Parva.

The Enigma of Jaimini

Jaimini is the celebrated author of the Purva Mimamsa and also of the Jaimini Bharata, fragments of which are turning up. Mairavanacaritam appears to be an independent work included in the Jaimini Bharata not claiming connection with any of the parvas. On the other hand, Sahasramukharavanacaritram or Sitavijaya claims to be a part of the Ashramavasa Parva of the Jaiminiya Mahabharata.

The link with Vyasa is visible as both these manuscripts have Sita and Hanuman using mantra-infused grass to consume the demons. In Vyasa’s Udyoga Parva (94. 27-30) Nara demolishes the army of Dambhodbhava by launching ishikabhir, blades of grass. Again, in the Shanti Parva (330. 48) Narayna takes an ishika, transforms it into an axe with a mantra and flings it at Rudra. Jaimini seems to have taken this concept from his guru.

Further, the invocation to Jaimini’s Ashvamedha Parva repeats Vyasa’s with a significant difference: he adds his guru’s name in the introductory namaskar:

narayanam namaskrrtya naram caiva narottamam /

devim sarasvatim vyasam tato jayam udirayet //

Vyasa is said to have assigned him the Sama Veda. In the Markandeya Purana (c. 250- 550 CE), Jaimini is the interlocutor. According to Monier-Williams, Kautsais his other name. [5] However, in the Mahabharata, Sauti tells Saunaka that in Janamejaya’s snake-sacrifice, “The learned old Brahmin Kautsa became the udgatri; Jaimini the brahmana.” [6] In Yaska’s Nirukta Kautsa is a commentator questioning the meaning of Vedic mantras and his arguments are presented in Jaimini’s Mimamsa Sutra (4th to 2nd century BC). [7]

Bulcke [8] dates Jaimini’s Ashvamedha Parva to the period after the composition of the Bhagavata Purana (8th-10th century CE), which Jaimini mentions. It was translated into Kannada [9] in the 13th century. Its Kusa-Lava episode is very similar to that in the Padma Purana’s Patalakhanda (c. 10th century CE). There were different “Jaiminis” writing under the same name, as with Vyasa, creating different texts across the centuries following the time-honoured tradition of the guru-shishya parampara. [10] The author of Mairavanacaritam and Sitavijaya (if they are the same person) would be one such “Jaimini.”

The concluding chapter of Mairavana provides a clue towards the probable time of its composition. There is a reference to the “six syllable mantra” in sloka 6 of chapter 20. This is ram ramaya nama? found in the Ramarahasya Upanishad,which is possibly of the 17th century. In it, Hanuman instructs Sanaka and other sages on how to worship Rama. Again, the paean to Hanuman (sloka 24 of chapter 18) as adept in the Vedas and its limbs and the shastras is paralleled by Tulsidas (1532-1623) in his Vinayapatrika, where he calls Hanuman vedavedantavid. [11] His Ramacharitmanas contains the Ahiravana tale. There is also a Sitopanishadcelebrating Sita as Shakti but, unfortunately, its period cannot be determined. [12]

The language of Mairavana and Sitavijaya is quite pedestrian, strangely devoid ofalankaras and rasas. The flamboyant poetry characterizing the Ashvamedha is entirely missing. Though one does come across the usual similes like, “burnt like trees in a forest fire,” or bathed in blood “looking like an Ashoka tree in full bloom,” or “arrows raining like rain from clouds,” the Ashvamedha’s striking use of metaphors and rhetoric is absent. The unexpected juxtaposition of opposites, the conceits, which the Jaimini of the Ashvamedha merrily uses, appears to be unknown to the Jaimini of Mairavana and Sitavijaya. Consider this from the Ashvamedha Parva:

Nandi could not seize Garuda as an angry elephant cannot seize cotton-wool in a courtyard (21.32); or,

…armour destroyed, Sita’s son stood on the battle-field like the newly-sloughed king of serpents (34.6); or,

Rama’s glowing iron arrows were as useless as a poor man’s desires in a miser’s home (36.58).

Mairavanacarita and Sitavijaya are bereft of such interesting conceits. The only common feature is the use of hyperbole, especially in battle. The Jaimini of the Ashvamedha exaggerates outrageously. However, in Mairavana and Sitavijayapeople do not grow on trees, horses do not turn into mares and tigresses, and no rakshasi has eight-mile-long breasts, which she uses as weapons in battle! The Ashvamedha effectively uses all the nine rasas. In Sitavijaya and Mairavana, only vira and bhayanaka with a sprinkling of raudra are seen, with adbhuta ruling. In Mairavana, Hanuman increases and decreases his body at will, creates an impregnable fort with his tail, Brahma constructs an amazing defence for Mairavana’s palace, Mairavana shape-shifts continually in battle, like Mahisasura fighting Durga. In Sitavijaya, Ravana has a thousand heads and two thousand arms, his brothers have hundreds of heads, eyes, bellies and hands, the diseases fight a terrific battle, Hanuman is given five heads, grass columns turn into blazing missiles, and so on.

A major difference between the Ashvamedha and these two manuscripts concerns variety. The Ashvamedha has many side stories, tales within tales, e.g. Agni and Svaha, Uddalaka and Chandi, Malini and Yama, Chandrahasa, Bakadalbhya, the golden mongoose, the quarrelling Brahmins, Babhruvahana’s exploits, etc. Almost all the sections contain different narratives. The battle sequences, the mainstay of all the three texts, are singularly dissimilar. Those in Sitavijaya are monotonous. The characters change, but the sequence of events is more or less the same in all, except the last battle in which Sita slays Sahasramukharavana with a grass-missile. Hanuman also uses mantra-infused blazing grass against Mairavana, but ineffectually. Here the descriptions of battles read more like the report of a war correspondent than literature. We miss the exuberance and creativity of theAshvamedha’s Jaimini.

Besides the heroic, the other ruling sentiment of the Ashvamedha is Vaishnava bhakti. All the protagonists worship Krishna even as they fight him, their bhakti masked by the animus they display outwardly as they wish to receive death as his grace. The battlefield is their temple where they worship their deity with weapons. Krishna is worsted by them because the essence of the concept of bhakti is that the deity must be overcome by the intensity of the bhakta’s bhakti.

In Mairavana and Sitavijaya there is little bhakti. While the former is dedicated to the glory of Rama and the latter to Krishna, there is but a single paean to Rama at the beginning of the former and at its end. The latter has paeans to Hanuman and to Sita’s wondrous form towards the end. How can an author, so immersed in Vaishnava bhakti in one work, be almost completely bereft of it and extol Hanuman and Shakti in the two others?

An underlying current of Shaivism runs through the Sahasramukharavanacaritam. The crisis it deals with is precipitated by two insults: the first is by the Trinity to Anasuya; the second is to Shiva’s avatar Durvasa at Mandhata’s yagya. The latter parallels the insult to Shiva at Daksa’s sacrifice, which is destroyed by Virabhadra and Kali, routing all the sages and devas. The names of Durvasa’s sons, who rout the devas, are among the thousand names of Shiva in Section 284 of the Mokshadharma Parva of the Mahabharata. The presence of Shiva in Vyasa’s Mahabharata is quite significant, though understated. Therefore, Jaimini is not blazing an altogether new trail here. The dreadful destructiveness of Durvasa’s sons is of a piece with other demons originating from Shiva such as Andhaka, Bhasmasura and Jalandhara. Here Hanuman is a product of Shiva’s sperm and has five faces like him. However, the heads of lion, horse and boar represent avatars of Vishnu and his mount Garuda. This is, therefore, a Hari-Hara image, a fusion of Vishnu and Shiva. Parallel to the pair of Virabhadra and Kali, we have here the pair of Hanuman and the shadow-Sita.

There is a feature that indicates the somewhat casual attitude of the author of these two works. The names of the characters take different forms at different places. Matangi becomes Sita, Ustramukha becomes Osthamukha, Vakranasa becomes Vakranetra, and so on. This is a defect noticed in both the texts. The sincerity with which the Ashvamedha was created is missing in these. However, these could be copyists’ errors.

The Ashvamedha Parva is characterised by flamboyance of description, be it of a road, of a palace, or of nature. Consider the rhetoric of the passage in which Vrishaketu describes a lake to Bhima (4.11-14):

“…the enjoyment the elephants are getting from these waters is like the pleasure the lustful men get from making love to women. The life-giving water is tinted deep red with the vermilion falling from the temples of these elephants. Since the temples of the elephants are now bereft of charity, the bees have now forsaken them and entered the clump of lotus plants. There is no loyalty among the mean. Picking up the lotus-stalks, the swans are generously offering them to the bees, like those who know the principle of equity among beings. The fish are leaping in the lake as poor people do on getting riches…”

There are many such instances throughout the text.

In Mairavana, there are only two descriptions: one of Ayodhya (section 1) and the other of a forest in Lanka (section 10, verses 2-6), of which the latter is the better one:-

“Having gone up to thirty yojanas,

a maha-forest was

afar, filled with bears, lions, tigers and

other animals and birds,

Narikela, panasa, amra,

patala, tinduka,

kapittha, jambunipa, jambira,

also nimbaka.

Filled with different trees it was like

Nandana.

Entering the forest, they saw a lake

of two yojanas,

Adorned with red and white lilies, crimson

and blue lotuses,

thousand-petalled lotuses and hundred-

petalled water-lilies,

All filled with cackling, teeming with

intoxicated bees,

the lake appeared like a sea adorned with

leaves all around.”

In Sitavijaya, there is only one description, that of the palace that Vishvakarma built for Ravana (8.33-41):

“In width a lakh yojanas, double that

in length, a fifty-

yojana high excellent wall adorning it,

With four ornamented towers, four gates,

maha-roads, adorned with

ten million palaces each with a

hundred horned doors.

On four sides four lakh maha-markets stood

adorning. The maha-

royal road was provided with countless

large seats.

Five thousand yojanas long was the king’s

palace, furnished

with an unfathomable moat impassable

for enemies,

Many sataghns and equipped with

all weaponry.

On four sides, placing Sudharma and the

other halls with care,

In the centre an immaculate

assembly hall

endued with wondrous attributes, with

a hundred gardens

filled with flags and garlands of pennants,

With qualities superior to the world

of devas, abounding

in markets and shops, mixed herds of maha-

elephants like

the Meru and Mandara mountains,

Inhabited by divine horses swift

as thought, adorned

with lotus lakes full of swans and cranes,

Better than the Trinity’s abodes,

radiant as

newly arisen Bhanu.”

The qualitative difference between the excerpts is obvious. How can a poet capable of describing so beautifully in the first instance hardly use his talent in two of his own works? So is it with the dialogues. In the Ashvamedha there is profusion and variety. Dialogue is used to establish characters and situations effectively. In Mairavana and Sitavijaya there is only martial talk and the occasional paean. These two texts cannot stand beside the poetic elegance and expanse of the Ashvamedha Parva. It is unlikely, therefore, that their author is the same, although they might belong to the same “Jaimini” school.

Is their Author the Same?

Were Mairavana and Sitavijaya composed by the same author? The language and the style seem similar. As in Mairavana Rama and Laksmana are abducted when asleep, so, too, in Sitavijaya are Bharata and Shatrughna. In both, mantra-infused grass is used as a missile and the supernatural prowess of Hanuman is celebrated.

However, an interesting difference in the colophons of these two works raises a doubt. The colophons in Mairavana mention Shri Jaiminibharata without stating the parva concerned. The colophons of Sitavijaya ascribe it to the Asramavasa Parva of the Jaiminiya Mahabharata. Would the same author composing two stories use different names in the colophons denoting the principal work of which these are parts?

It is pertinent to recall that Vyasa first composed the Bharata of 24,000 slokas, without the fringe episodes:-

“Originally the Bharata, without the fringe episodes, consisted of twenty four thousand slokas: this, to the learned, is the real epic.” [13]

caturvimsatisahasrim cakre bharatasamhitam /

upakhyanair vina tavad bharatam procyate budhaih // [14]

Is Mairavanacarita part of Jaimini’s version of the Bharata? But, then, is it not a fringe episode?

Parallels and Variations

Our tribes have analogous versions of both the stories Jaimini relates. [15] Writing on the Mundas of Chhotanagpur, K.S. Singh notes that they believe the vanaraswere forest dwelling tribes who wore part of their dhoti trailing loose as a tail, as the Mundas and Savaras still do on their dancing ground. [16] The episodes also occur in Ramayana retellings and plays in South East Asian countries. However, there is no mention of these two stories in the Rama tales of Sri Lanka, Tibet, Khotan, Mongolia, China, Japan and Vietnam (Champa).

Sahasramukharavanacaritam or Sitavijaya

The Agarias, an ironsmith tribe of Madhya Pradesh, have a tale in which Sita tells Rama about a thousand headed Ravana in Patala. He pulls out from his foot the arrow Rama shoots at him and despatches it to kill the sender. Rama falls. Sita, frightened, goes to Lohripur and asks Logundi Raja to send Agyasur and Lohasur with half an earthen pot of charcoal. By its smoke, she turns black. Carrying the pot in one hand and a sword in the other, she cuts off Ravana’s heads. Agyasur and Lohasur lick up the blood. [17] Thereafter, according to a tale in Braja literature, Sita becomes Kali-mai (mother Kali) in Calcutta. [18] The Marathi Shatamukharavana Vadha (19th century) by Amritrao Oak also narrates the killing of this demon. [19]

There are Tamil two tales relating to the hundred headed and thousand-headed Ravanas, Sadamuka Ravanan Kathai, Sahasramuka Ravanan Kathai, that do not not occur in Kamban. [20] In Telegu there is a similar Shatakantha tale, which occurs in Assamese, Oriya and Bengali Ramayanas too. [21] In the Uttarakandaof Ramamohan Bandopadhyaya’s Ramayana (1838), the tale is retold along the lines of Chandi’s killing of the demons Shumbha-Nishumbha.[22]

In Sanskrit the Adbhut Ramayana [23] and Ramadasa’s Ananda Ramayana [24] (both c.15th century) relate how Sita kills the hundred and thousand headed demons. Rama Brahmananda’s Tattvasangraha Ramayana (17th century) has five-headed Hanuman helping eighteen-handed Sita to kill the hundred-headed demon. [25]

Jaimini’s version, running to fifty chapters, is very different. The interlocutor is Janamejaya and the narrator is Jaimini. However, in slokas 10-11 of the first chapter, the last verse of the second and slokas 30-31 of chapter 50 at the very end, there is someone else, nameless, who is narrating what Jamini told Janamejaya. This would be a suta, a wandering rhapsode. He is never named here.

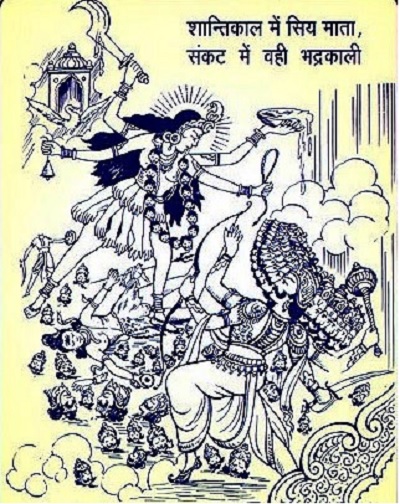

Jaimini alone provides the cause for the birth of the thousand-headed demon along with his brothers, with hundred heads, hundred bellies, hundred tongues and hundred eyes, viz. the insult to Anasuya by the Trinity and to Durvasa in Mandhata’s sacrifice. Bharata and Shatrughna are abducted and married off (without any demur) to the demon’s daughters. In the battle the devas, monkeys, rakshasas, kshatriya kings with their armies, Rama and even the Trinity fall. That is when Sita takes the field, bestowing five heads on Hanuman with which he devours the demonic army. With fiery grass columns she despatches the thousand-headed demon. Rama is not terrified of her, as her form is not horrifying, though wondrous. After being paeaned at length, Sita joins Rama and all return to their abodes. The demon’s city is divided between Citradhvaja and Citraratha, the sons of Bharata and Shatrughna who are not mentioned in any Ramayana. There is no mention of Bharata and Shatrughna being accompanied by their new wives when the four brothers meet their mothers back home.

What is of great interest is that here Sita does not abandon Rama and her sons to disappear into the bowels of the earth. All kings condemn the washerman (there is only this cryptic mention) and praise Sita, whom Rama embraces. Brahma gives him a span of eleven thousand years to rule, as in Valmiki.

Janamejaya is eager to know what further deeds Rama did after the return to Ayodhya. Jaimini responds by telling Janamejaya that what he has been narrating so far is (part of) the story renowned as Ashramavasa Parva beginning from the victory of Sita till the death of King Dhritarashtra. The closing benediction dedicates the work to Krishna.

Mairavanacaritam

The tale is completed in twenty chapters. Jaimini’s creation is quite distinct from other versions. It is not an episode composed by Valmiki, but by Jaimini and is narrated by Agastya to Rama to celebrate a wondrous nocturnal deed of Hanuman. He rescued Rama and Laksmana who were overcome by an enchanted sleep and abducted by Mairavana to the nether world.

In Jaimini it is not Laksmana but Rama who, enraged with Shurpanakhi’s amorous advances, cuts off her nose as Ravana informs Mairavana. Indeed, in the entire story, neither brother has any role to play, being asleep throughout.

The story of Mahi (earth) or Mai (collyrium or black in Tamil) Ravana is a celebration of Hanuman’s prowess and intelligence. It was far more popular than tales about multiple-headed demons other than Ravana. Besides Sanskrit, it exists in Gujarati, Marathi, Malayalam, Kannada, Tamil, Nepali, Bengali, Oriya, Assamese, Hindi, Thai, Lao, Khmer, Malay and Burmese and has many tribal variations. It is not surprising that some manuscripts are entitled Hanumadvijaya, the victory of Hanuman. [26]

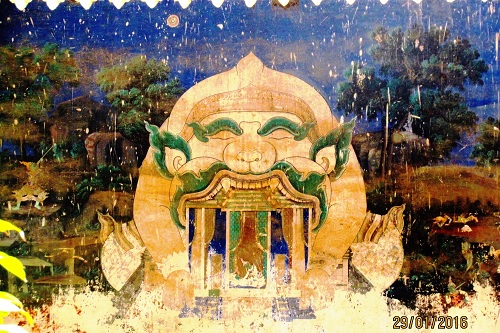

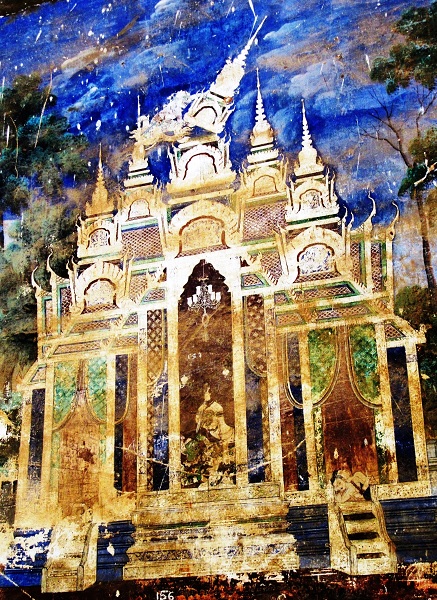

In Cambodia, on the walls of the Silver Pagoda in Phnom Penh, extending for 642 metres, reaching a height of 3.65 metres, frescoes of scenes from the Ramayana were painted during 1903-04 by a team of 49 artists led by Oknha Tep Nimith Theak. [27] Among these is a huge fresco depicting Mairavana’s abduction of Rama and the rescue by Hanuman.

|

Many films have been made about the story since 1922 in Marathi, Tamil, Hindi and Telegu. [28] Not a single film, however, has been made about Sita and the Thousand-Headed Ravana. In the recent television serial on Star Plus channel, Siya ke Ram (2016), however, this incident features as episode 256. [29] In Sanskrit, Advaita’s Ramalingamrita (dated 1608) and Ramadasa’s Ananda Ramayana recount how Ahirava?a and Mahiravana take Rama-Laksmana to the netherworld and how Hanuman kills them with the help of his son Makaradhvaja and a Naga’s daughter in love with Rama. [30] The matter of Jaimini’s Mairavanacaritam is virtually the same, except that:-

The bard states that this narrative was not related by rishi Valmiki, who considered that the bringing of the medicinal herbs by Hanuman was heroic enough, but was narrated by Jaimini. The final benedictory verses state that the Ramayana or the Mahabharata must be in every village, otherwise an expiatory vow must be observed. Hanuman’s twelve names are given as the mantra for success. One would have expected the Hanumannatakam [31] or Mahanatakam to narrate these wondrous exploits of Hanuman alongside Sita and his rescue of Rama and Laksmana. Strangely enough, they do not feature in this Sanskrit play whose author is supposed to be none other than Hanuman himself. Abridged version of K.K.Handique Memorial Lecture delivered by the author at The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, on 4th August 2017 All images photographed by the Author References [1] P. Lal: The Mahabharata of Vyasa: The Complete Adi Parva, Writers Workshop, Calcutta, 2005, (the last two lines have been amended by me to make it a faithful translation). |

K.K. Handique Memorial Lecture at the Asiatic Society

On 4th August 2017 at 4pm Dr Pradip Bhattacharya will be delivering the K.K. Handique Memorial Lecture at the Asiatic Society, Calcutta. He will speak on his Critical Edition of 2 palm-leaf mss in Grantha script from the lost Jaiminiya Mahabharata.

On 4th August 2017 at 4pm Dr Pradip Bhattacharya will be delivering the K.K. Handique Memorial Lecture at the Asiatic Society, Calcutta. He will speak on his Critical Edition of 2 palm-leaf mss in Grantha script from the lost Jaiminiya Mahabharata.