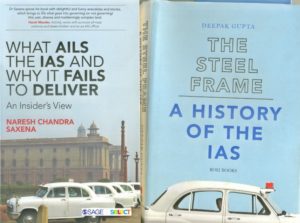

The Steel Frame: A History of the IAS by Deepak Gupta. Roli Books, 2019, New Delhi, pp. 354, Rs. 695. ISBN: 978-81-938608-4-7

What ails the IAS and Why it fails to deliver by Naresh Chandra Saxena. Sage, 2019, New Delhi, pp. 245, Rs. 595. ISBN: 978-93-532-8648-4 (PB)

Gupta (IAS 1974) as chairman of the Union Public Service Commission made a signal contribution by building up its archives. Drawing upon that repository, he has written a history of the Indian Administrative Service, calling it, “The Steel Frame,” which was how Lloyd George described the Imperial (later Indian) Civil Service. After all, the Indian administrator was envisaged as the imperial civil servant’s avatar!

Gupta splits his account into nine chapters: the historical context; Indianization; transition from the ICS to the IAS; the District Officer’s role and experiences; character of the ICS and the IAS; IAS transformed; the examination scheme; training the civil servant; reinventing the IAS. There is a good bibliography along with ten appendices, the last two being autobiographical. His target audience is IAS aspirants: “The idea of public service itself has got devalued. We must restore it as a predominant aspiration…This study will be both useful and interesting, not only for those who have been in the services, but also those aspiring to join.” The historical account is punctuated with references to his family, whose members occupied top government posts: father in the Imperial Police, uncles in the ICS and the IFS, two brothers in the IAS. As we read, the impression grows that it is more the history of the ICS than of the IAS. Though chronologically unavoidable, was it necessary to trace so laboriously every step on the way from the East India Company’s covenanted civil service till the first entrance examination in 1855? As the IAS is still evolving after the Kothari Commission’s drastic changes, any survey that concentrates on the post-1980s is of interest. There is too much of the past and not enough of the present.

Gupta unearths quite a few nuggets of information. Clive, as C-in-C of the East India Company’s forces, urged its Directors to be aware of “The evil…of the military…attempt to be independent of (civil) authority.” The Court of Directors’ letter of 21 July 1786 prescribed that in coordination meetings the senior-most civil servant—whatever his rank—would preside. Often the police have jibbed against it, even avoiding meetings convened by district magistrates during the Siddhartha Ray regime in West Bengal. Gupta points out that Pakistan abandoned the principle, “with dramatic consequences for the contrasting development of democracy and the nature of the State in the two countries.” The plain fact remains that rulers favour the weapon-wielding uniformed force over the magistrate, which encourages the police to distance themselves from supervision by civil authorities who, to save themselves from embarrassment, have stopped inspecting police stations.

Another nugget is the Government of India (GOI)’s minute of July 1907 to the Islington Commission on a uniform legal code being essential for ensuring justice in public administration since, from inception, “the young Civilian is in part a lawyer and in part a judge.” A grasp over laws and the development of a discriminating intelligence that knows when to use discretion, remain the foundation of an IAS officer’s personality. Gupta provides the interesting information that Rajendra Prasad was obsessed with sitting for the ICS but was prevented, and that Nehru did not “disfavour the idea of joining the ICS…there was a glamour about it.” N.C. Saxena tells us how the ICS was prized: in 1935 an ICS secretary to GOI earned Rs.6, 666 whereas his counterpart in the USA got half as much! That was revised drastically downwards after 1947.

The major change in recent times is that servicemen’s children are not interested in joining. Gupta writes, “The increasing decline in the authority of the servicemen as political domination through the instruments of control and patronage increased over the service and its members also served as a dis-incentive.” The upper middle-class background of the ICS and the IAS has been replaced by diverse economic and social strata. Liberal education has been largely replaced by candidates from technical, management and medical backgrounds. A civil services survey of 2010 finds that the core motive is getting a prime job providing security, social status and prestige. Add to this the opportunity for extending patronage and making money (through dowry and otherwise), for which many officers have been indicted in recent years. This is why candidates reappear repeatedly, investing significant labour, time and finances.

The watershed in the changing nature of the IAS was Indira Gandhi when she called for a “committed bureaucracy” loyal to her in person. In Rajiv Gandhi’s time, writes Madhav Godbole (who resigned as Home Secretary), civil servants were treated like politicians’ office peons. Subsequent regimes saw businessmen, astrologers, godmen calling the shots. Narasimha Rao granted extensions to retiring Secretaries: “…the rapid downhill journey continued.” The key word describing the civil servant in demand became, “pliable”. This was Indira Gandhi’s criterion for selecting the Director of the National Academy of Administration to replace P.S. Appu, which the UPA government followed too. Gupta pulls no punches in dealing with the scandalous coal block case, pointing out the dubious role of the Prime Minister’s Office and the abandonment of the principle of ministerial responsibility. Against this lies the resignation of Krishnamachari as Finance Minister in the Mundhra case in Nehru’s time. The Finance Secretary, H.M. Patel ICS, also had to resign but then became Morarji Desai’s Finance Minister and Charan Singh’s Home Minister! The swift whittling away of public accountability, the inaction on the reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General, the weakening of the Central Vigilance Commission, the Election Commission, the CBI, all show how ineffective the civil services have become by the ruling party’s cunning use of the carrot-and-stick policy. Moreover, unlike the ICS, today the IAS “is divided by caste, class, age, educational background, state of origin, and increasingly by careerism.” The greatest challenge “is to find its own esprit de corps” which is impossible without a shared sense of purpose and values. Therefore, the recruitment system has to be changed, as also the induction training. Is the IAS officer’s greatest enemy his senior colleague? In the ICS camaraderie existed possibly because of the small numbers.

With Gupta belonging to the Bihar cadre, it is surprising to find no reference to the sterling example set by P. S. Appu, the Chief Secretary during Karpoori Thakur’s time. He was the architect of land reforms in India and an expert on poverty studies. N.C. Saxena notes in his book how, when Thakur asked him to become the CS, he not only wrote to him pointing out that there were others senior to him, but also, when Thakur insisted, put forward several conditions regarding how he and his colleagues would discharge their duties. Finding that the conditions were not met, he left and joined a junior post in GOI. Finally, he resigned from the IAS in protest against the GOI not dismissing a culpable IAS trainee.

Saxena’s book is in eleven chapters, with headline-grabbing headings: tussle for power; officers in headlines; bureaucracy (read, ‘IAS’) responsible for sedimentary development; is the IAS good at designing programmes; is the IAS fair to marginalized groups; the strange case of Bihar; corruption in the IAS; is civil society a substitute for the IAS or just trouble-shooters; IAS unmasked.

Turning to his book from Gupta’s is a refreshing contrast as he writes pithily, hitting hard, punctuating it with wry humour. Because of his style, his criticisms and suggestions never sound like pontification. It is a measure of the type of person Saxena is that he has chosen our student Harsh Mander (who resigned from the IAS after the Gujarat riots) to write the Foreword. Harsh Mander recalls how, led by Saxena, in the LBSNAA (1993-96) the faculty encouraged recruits “to reflect, question, dissent; to imbibe the values of the Constitution and of public service.” For doing exactly this during Appu’s directorship in the early 1980s some of my senior colleagues and I were transferred by GOI.

Saxena puts his finger right on the spot. It is not that officers are not hard-working and honest. “But people are more interested in the outcomes…rather than in their personal qualities.” The officers’ fixation with financial outlays and expenditure neglects the crucial issue of what the funds are meant to achieve. Despite his strenuous efforts, Saxena could not get Vajpayee as the PM to understand this (he simply shut his eyes during a presentation!) and was shifted out. In UP the chief minister was quite frank, explaining that he would lose votes by legislating land rights for women. Lalu Prasad Yadav in Bihar held up funds released by GOI so as to foster a rule of inequity and exploitation, actively assisted by Mukund Prasad, the chief secretary who was, however, personally honest. Here, subscribing to the politician’s objectives superseded serving the people.

Saxena’s book is peppered with many an interesting tale illustrating the ups-and-downs of the Minister-IAS interaction. Each is retold with a light touch which rams the lesson home all the more soundly. In the early days, seniors would groom and protect juniors, while lately it is “each for oneself”. There is the astonishing account of Saxena as secretary Planning Commission giving the Orissa chief minister Giridhar Gamang an extra Rs. 50 crore to change the anti-tribal law about minor forest produce!

Saxena confesses that despite his many initiatives in land reforms, forestry, minorities commission, rural development, there was no sustained improvement and he was punished as well. Seeking answers, he ponders, “Stand-alone bureaucratic initiatives have little lasting value unless supported by strong political ownership.” The 1972 Task Force on land reforms under P.S. Appu had pinpointed lack of political will as the key factor in failure. As examples of both coalescing, Saxena cites my trainee Parameswaran Iyer’s achievements with the Swacch Bharat Mission, Bihar’s turn-about under Nitish Kumar as CM, Chhattisgarh delivering subsidized rice to the poor, Madhya Pradesh tripling wheat production in a decade. Saxena poses ten questions to his critics (pp.7-8) which will make most officers squirm. One of these is about serving in backward areas. I was much criticised for getting new recruits posted as block development officers—just for three months—in 1975. 30 years later there was the same criticism when I got them posted as subdivisional officers in tribal areas in West Bengal.

One reason Saxena does not mention for why initiatives flounder is that in the IAS nothing succeeds like the successor. Rarely does an officer build upon his predecessor’s initiatives. History must be made anew! S.B. Agnihotri (1980, Orissa) explained to me: “You are all like the Rajputs, each fighting the battle alone. Unless you band together, change will never happen.” Saxena calls it, “the absence of collective will,” and as examples cites the 1988 Forest Policy and the 1999 Sanitation Policy. Very rarely has the IAS stood together as a community. Once was when all the 1980 batch trainees wrote to GOI against accepting P.S. Appu’s resignation. This is all the more unique as they had not been confirmed in service. It is this “nexus of good” that another of my trainees, Anil Swarup, former Education Secretary GOI, has been advocating since retirement. Saxena presents short accounts of officers who have stood up for public service at great cost to themselves: Durga Shakti Nagpal, H.C. Gupta, P.S. Appu, S.R. Sankaran, Armstrong Pame, Ashok Khemka, Arun Bhatia, Harsh Mander. The omission of Aruna Roy, architect of the Right to Information, is surprising as is that of K.B. Saxena, B.D. Sharma and A.R. Bandopadhyaya.

It is a conundrum that the areas of social welfare—health, education, pollution—are not only the least well-funded, but also have the largest number of field-level vacancies next to the police. While politicians cry themselves hoarse over benefits not reaching the deprived, they never provide staff to deliver the benefits. ‘Garibi Hatao’ has become the slogan for anyone in power to siphon off government funds into their pockets. Officers quickly take jobs with business houses without any cooling-off period (e.g. the former HRD Secretary of GOI presented the case of the non-existent JIO University to be recognised as an institute of eminence; Kingfisher Airlines’ board had many retired IAS officers). They also join political parties, casting doubts on their impartiality while in service (e.g. K.J. Alphons and P.L. Punia who is not of the 1970 batch as he states, but 1971). He could have included Yashwant Sinha,[1] who was Karpoori Thakur’s principal secretary.

Corruption “is a low-risk and high-reward activity’ writes Saxena and lists six suggestions on how to reduce corruption—all sound, well known, but never pursued in the absence of political will and accountability. Legislatures never examine whether objectives have been achieved, nor pursue omissions pointed out by the C&AG. Legislators do not educate constituents about rights that new laws provide. Businessmen get elected for advance knowledge of new laws that will affect them. However much an IAS secretary may advise a minister, if that is ignored, there is nothing he can do. He can, at best, refuse to carry out the orders and be transferred. What makes Saxena special is that in such cases he highlighted the matter in the press, disregarding the consequences. Interestingly, Saxena finds neither Manmohan Singh nor Montek Ahluwalia much concerned about the disadvantaged. “It was only Sonia Gandhi who tried to temper hard market fundamentalism with compassion and equity, and this I believe was her most valuable and least acknowledge contribution to Indian public life.”

Much of what is wrong with governance had been highlighted in the Shah Commission Report (1978), e.g. “civil servants felt that they had to show loyalty to the party in power in order to advance their careers.” The UPA government suppressed it. The Modi government conferred the Bharat Ratna on one specifically indicted by it. A wealth of valuable insights is found in books by P.S. Appu,[2] M.N. Buch,[3] and N. Vittal,[4] which neither Gupta nor Saxena draw upon. Nor do they refer to the brutal findings of the N.N. Vohra Committee (1993) regarding the noxious nexus between business, mafia, police, civil services and even the judiciary. Parliament merely “took note” of it; the Supreme Court asked for an action-taken report and forgot about it; so did civil society.

Finally, Saxena points out, “a dilapidated civil service has been a key factor in Africa’s economic decline. Conversely, a strong civil service is one of several reasons” why East Asian countries have done so well. “Kleptocracy,” exploiting national resources for personal benefit, is what plagues India. The IAS can still deliver if it is “more outcome oriented and accountable for results.”

Published in the Oct-Nov 2019 issue of BIBLIO

[1] Relentless—an autobiography, Bloomsbury, 2019.

[2] The Appu Papers; Crisis of Convergence, introductions by J.M. Lyngdoh, A.R. Bandopadhyaya, Sahitya Samsad, Kolkata, 2007, 2008.

[3] When the Harvest Moon is Blue, Haranand, New Delhi, 2010.

[4] The Red Tape Guerrilla, Vikas, New Delhi, 1996.