KRISHNA AGAINST THE KURU-PAANDAVS

THE APOCRYPHAL DANDI PARVA OF THE MAHABHARATA

Introduction

The core story of the Mahabharata is well-known: how Krishna helps the five Paandav brothers (three Parths and the twin Maadreyas), sons-and-stepsons of his paternal aunt Pritha-Kunti, win the kingdom of Hastinapur with their seven armies from the eleven armies of Duryodhan and his ninety-nine brothers on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. However, little known is the tale of the sons of Dhritarashtra and Pandu, allied with Jaraasandh of Magadh and Shishupal of Chedi, jointly opposing Krishna and the Yaadavs in battle. It is this tale that formed the matter of Paandav Gaurav (1900), a five-act play in Bengali by Girish Chandra Ghosh, the founder of Bengali theatre, that was a runaway hit on the Calcutta stage. What was his source?

The version of the Mahabharata that we know is what Vaishampaayan recited to Raja Janamejay at Taxila at the bidding of his guru Krishna Dvaipaayan Vyas during intervals of the holocaust of snakes the king had organised to avenge his father Parikshit’s assassination by Takshak naga. Heard there by the bard Ugrashravas Sauti, it was recited by him to Rishi Shaunak and his group of ascetics in the ashram at Naimish forest during intervals of their twelve-year-long yajna. Besides this version, there is another by another of Vyas’ pupils, Jaimini, of which only a few parvas are extant. From his Ashvamedha Parva Girish Ghosh took the very unusual story of Queen Jvaalaa and wrote a successful play on her named Janaa (1894).

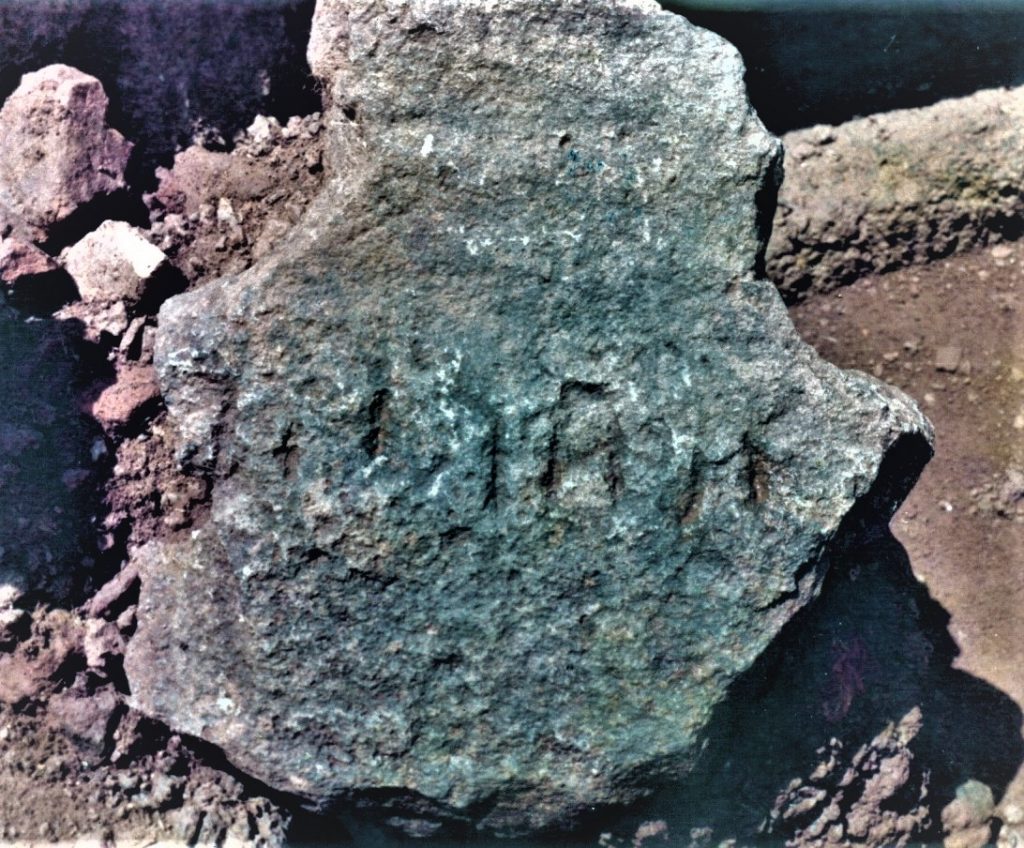

Moreover, there is an apocryphal text entitled Mahabharata: Dandi Parva attributed to Krishna Dvaipaayan Vyas narrating, inter alia, the startling story of how the Paandavs and the Kauravs jointly opposed Krishna in battle, which provided Girish Ghosh the material for his play. This rare Sanskrit text was translated into Bengali by Pandit Kaliprasanna Vidyaratna and published in 1900 (reprinted in 1987 by Nabapatra Prakashan, Calcutta). Dinesh Chandra Sen states in his Bangabhasha O Sahitya (pp. 424, 427) that he found a translation in Bengali poetry by Rajaram Datta, containing 1500 verses, the manuscript of which written by Ramprasad Dey is dated to 1809 CE. However, the introduction states that it was composed by (or at the behest of) Nrisimha Das son of Ramkanai Das in the “poyar” metre of 14 letters after studying the Brihat Kurma Purana. This Purana consists of four samhitas: Brahmi, Bhagavati, Sauri and Vaishnavi, of which the Brahmi Samhita is also known as the Kurma Purana. Besides the story of Raja Dandi and Urvashi, it contains the curious tale of Shrivatsa narrated by Krishna to Yudhishthira to console him during the forest-exile. Apparently, Girish Ghosh’s source was a poetic composition called “Dandi Parva” (1870) by Umakanta Chattopadhyay in which the narrator is Shukadeva Goswami, Vyas’s son. Prior to that Rohininandan Sarkar’s “Dandiparva by Maharshi Vedavyasa” had come out in 1885 and in 1886 Prankrishna Ghosh had written “Dandi-charit-ba- Urvashir-Abhishap” (Dandi’s Deeds or Urvashi’s Curse).

What distinguishes this work from the Mahabharata is the excessive overlay of Vaishnava bhakti and unnecessary excursions into didactic peroration at the slightest opportunity, indicating its composition in late medieval times. Further, the stereotype of women as foolish, incapable of taking sound decisions by themselves without the guidance of father, husband or son is repeated often, except in the case of Rukmini, possibly because she is Krishna’s consort.

Parikshit’s Birth and Curse

Rishi Shaunak exhorts the wandering rhapsode Sauti, praising him for his Vaishnava-bhakti, to narrate the story of Bhagwan to enable the audience to achieve salvation in the context of the impending dreadful Kali Yuga and enquires why Raja Parikshit, born into the blessed Paandav family, committed sin.

Sauti then narrates that in his earlier birth Parikshit was a Gandharva named Vidyadhar who used to sing daily in Indra’s celestial court and, waxing proud of his melodious voice, his intellect was overcast by pride. In the season of spring youthful Vidyadhar was overcome with desire for his young wife. Drunk with liquor, both entered the Nandan garden, whose enchanting environs aggravated his loss of self-control and he began singing lewd songs loudly. This disturbed the blessed rishi Parvat who was seated there speaking to his disciples on salvation. Parvat, approaching the Gandharva, requested him to be restrained and not disturb the peace. Vidyadhar insolently told him that this garden was suitable for enjoyment by him and his companions, servitors of Lord Indra, not for ascetics. If they felt disturbed, they should leave the place. Parvat again warned him that being drunk he was misbehaving, but Vidyadhar boasted he was accountable only to Indra and did not care about anyone else’s anger. Urged by his disciples to discipline the arrogant singer, Parvat cursed Vidyadhar that as punishment for the insult he would take human birth and be consumed by a Brahman’s curse. Overwhelmed with depression and terror, Vidyadhar begged to be spared human birth, that most miserable of all existences. His women also pleaded with the sage for mercy, but Parvat was adamant on cleansing Svarga of the pollution caused by Vidyadhar’s ill-conduct. However, he told him that he would be born in the supremely pure and renowned Paandav family and regain his station after his sins had been burnt away. Indra did not intervene. Thus Vidyadhar was reborn as Parikshit. Yudhishthir gave him this name because he was born when the Paandav dynasty was almost extinguished. Unlike the Mahabharata, which knows of no previous birth of Parikshit, here there is no reference to his being still-born and the resurrection by Krishna.

Parikshit was anointed Crown-Prince by Krishna himself and imparted advice regarding governance by Dhaumya, the family priest of the Paandavs, and Naarad. The sage Kanva advised regarding discarding desire and keeping good company. Sage Lompad advised on moksha-dharma. Vibhanda described the horrors of hundreds of hells and the nature of the Brahman. Krishaashva discoursed on the four classes, the four stages of life and the primacy of domestic life in sustaining the rest. Sage Deval spoke on the dharma of donating, celebrating ahimsa as the supreme dharma and on abstaining from liquor and indulgence in coition, as these were sources of delusion.

Despite all this, after ruling well for years, because of the rishi’s curse Parikshit went to hunt in a forest where the ascetic Shamik lived. Causing havoc among animals, he shot a deer which fled. Giving chase, Parikshit got exhausted, parched and sought for water from the monk who was observing a vow of silence, seated in ascesis. Distracted by hunger and thirst, enraged at the silence, Parikshit insulted the monk by draping a dead snake round his neck. Shamik’s son Shringi infuriated by this cursed that the culprit would die of snake-bite within a week. Shamik rebuked his son for cursing the raja and despatched a disciple to warn the king.

Overwhelmed, Parikshit went to the banks of the Bhagirathi and pleaded with sages to rescue him. Vyas also arrived and told him that instead of punishment, cleansing the character was more important. As he himself did not have the time, he deputed his son Shuka for the purpose. (This setting copies that of the Bhaagavat Purana and there are echoes of the Pururavas-Urvashi myth in the tale.) Parikshit begged the sage to tell the tale of why Bhagwan Vaasudev (Krishna) had opposed his favourite Paandavs in battle. Then Shuka recounted the holy tale of Raja Dandi to him.

Urvashi cursed by Durvasa

Once, after spending a thousand years in ascesis, the rishi Durvasa began roaming the world to satisfy his senses but was not satisfied. Then he proceeded to the abode of the immortals and was delighted to see its unique splendour. Seated alongside the devas in their court named Sudharma, he passed much time. To entertain him, Indra summoned the loveliest of apsaras Urvashi and bade her delight the sage with her dance. Urvashi, repelled by the body-odour, matted hair and dirty appearance, doubted his capacity to appreciate her skills. Durvasa immediately made out from her facial expression what she was thinking and roared aloud that sin must never be tolerated. Hence, as she had thought he was beastly, she would fall from Svarga to earth and be born as a mare to expiate her sin. Urvashi and all the devas begged the sage to set a limit to her suffering, whereupon warning her never to be proud again, he said that on earth she would live in the kingdom of Raja Dandi of Avanti and return when the curse was spent. Remaining a mare during the day, she would become a divinely lovely woman at night.

Thus Urvashi descended as a mare in a lovely wood in the wonderful kingdom of Avanti (in Central India) where everyone was good, festivals were held and no dangers existed. Raja Dandi was an excellent ruler, touring everywhere to supervise his subjects’ welfare. Once, when in distress because of her state the mare was running hither and thither, scaring the animals, Dandi arrived to hunt. He came upon the splendid mare in the company of some deer and ordered his troops to capture her. Leaving them all behind, Urvashi sped off deep into the forest. Pursuing her, Dandi was exhausted. Out of pity Urvashi spoke to him, enquiring who he was. Dandi was enchanted and declared his identity. Urvashi recalled Durvasa’s prophecy and lamented her state. By this time the sun had set and, losing the form of a mare, Urvashi became a captivating woman, stunning Dandi. She explained the entire matter to him. Dandi begged her to become his and assured to keep her hidden from all eyes. Urvashi agreed on condition that he vowed never to abandon her. Dandi promised immediately. Spending the night with her, Dandi took her back in the form of a mare to his capital and kept her in a secret place away from all eyes. Day and night he spent with her, neglecting all duties. Dandi was obsessed with the mare who became his sole concern, grooming and feeding her with his own hands all day long. Subjects and ministers had no access to him. At night when she became an enchanting woman, Dandi would devote himself to pleasing her as best as he could, regardless of his diminishing fame. His intelligence waned, his spirit dulled. Devi Lakshmi decided to abandon him and he became incapable of protecting his kingdom. The subjects began to suffer from sickness, untimely death and various sorrows, afflicted by robbers. Teenage widows and beggars began to abound.

The splendour of Svarga waned as well. Indra felt the absence of Urvashi acutely and was apprehensive of her having to face great suffering. Therefore, he summoned the celestial rishi Naarad and requested his intervention. Naarad assured him that the time was near for Urvashi’s curse to be lifted. Eager to have darshan of Shri Hari (Krishna), he proceeded to that very unholy place, earth. Naarad went to Dwarka, that city of unrivalled splendour because of Shri Hari’s presence and waited at the entrance for permission to enter, having due regard to royal protocol. Already aware of his impending arrival, Shri Hari had sent a guard to usher in the sage to where he was seated with Devi Rukmini. Crossing the apartments of 16,000 women, Naarad arrived where Shri Hari was seated. Greeting all the children, the aged and the women, Naarad found that wherever he looked in the inner apartments he saw Shri Hari present. Bewildered, when he willed to see Shri Hari at one spot, he found him seated before him with all his women, welcoming him. Having embraced him, Shri Hari enquired after his welfare, whereupon Naarad begged him to remove the curse from Urvashi and left.

Shri Hari despatched an envoy to Raja Dandi with this message: “O ruler of Avanti! The magical mare you have obtained and enjoyed in secret for so long, despatch it forthwith to me in Dwarka city. Do not do otherwise!” Hearing this, the king flared up with rage and shouted, “Get out! I do not know your master. If you tarry even a moment here, mighty Dandi’s deadly rod will split your body into pieces like Indra’s vajra or Shiva’s trident.” The envoy left immediately and reported everything to his master.

Krishna mused for a while that nothing of significance ought to be done in a hurry. So he summoned his intimate companion Uddhav and asked him to proceed to the city of Avanti. Crossing many lands, Uddhav reached Avanti soon and called on Dandi. Uddhav urged him not to dispute with Krishna who was the supreme divinity and to hand over the splendid mare to avert disaster. Dandi felt dizzy, bewildered, unable to decide what to do. Then to deceive Uddhav he said, “Why should I unnecessarily quarrel with Vaasudev to whom I pay tribute? If I had the mare I would definitely have handed it over. Someone has mistakenly informed you that I have found a mare. I am lucky that hearing that news you have set foot in my kingdom. If you do not believe me, please visit my palace and see for yourself.” Laughing, Uddhav said that he was not deceived by the king’s lies and that Dandi was only inviting misfortune thereby. “Alas, O king! Your intelligence is lost because of a petty thing,” said Uddhav taking leave.

Deeply disturbed, Dandi began to lament. Seeing his distracted condition, his queen urged him to concentrate on saving himself. Dandi argued that keeping his word to the mare was more sacred than obeying Krishna. Further, it was destiny that had made his mind thus obsessed, so there was no way out for him but to flee for saving his life as Krishna was sure to launch an attack after hearing of his refusal from the envoy.

Ardently embracing and kissing the mare, he exited the city in secret on her back, all alone. He roamed one land after another, from town to town, village to village like a madman, without any goal in mind. Gradually he came to his senses and decided he needed to seek for some way out of the predicament. First he approached the sea and prayed to it, but the sea declined as its glory was all Vaasudev’s doing and he could not protect Dandi against the Lord.

Then, one after another, Dandi approached Krishna’s foes: Shishupal lord of Chedi and mighty Jaraasandh of Magadh from whom Krishna had fled to Dwarka. Both turned him down, one because of Krishna’s invincible discus and as he was kin, the other as he considered it beneath his dignity to fight such a petty person.

Depressed and disappointed, Dandi decided not to approach any human being as men were incapable of protecting. Therefore, he presented himself before the lord of mountains, Himgiri and sought refuge with him. Acknowledging his right to be granted refuge, the Himalayas expressed its inability to protect him against the omnipotent one and advised him to seek shelter with Shri Krishna immediately.

His intelligence overcast, Dandi rejected the advice as venomous and abusing the lord of mountains proceeded to meet Duryodhan who said that he neither wished nor was able to oppose invincible Krishna. He advised Dandi to hand over the mare to Krishna and be free from danger.

Dandi then considered approaching the supremely righteous Yudhishthir who was celebrated as the support of the helpless. “But being an intimate of Krishna’s, if he asked Dandi to surrender the mare, what then? So long as he was alive, he could not give up the mare. It did not befit a man to break his given word.” He was unable to decide what to do and kept lamenting.

***

The Tale of Shrivatsa

“This is what happens,” said Shuka, “when the planets are unfavourable. Because of that Raja Shrivatsa had to live among the lowly born with his wife like an orphan.” Parikshit then begged him to narrate this tale of Shrivatsa that was unknown to him. Shuka told him that during the period of exile in the forest, Yudhishthira was deeply depressed. That is when Krishna came to him and narrated the story of Shrivatsa to console him. First, at Parikshit’s request, after narrating the lineage of Parikshit, starting from Daksha Prajaapati’s 50 daughters from 13 of whom rishi Kashyap produced humans and others, Shuka narrated the deeds of the Paandavs in brief till the forest-exile.

Shri Krishna told Yudhishthir that in the past noble Citrarath was installed as emperor of the earth. Shrivatsa was his only son, a store of all qualities. He was a king during whose rule the happiness of subjects was boundless. Constantly all of them sincerely prayed for the king’s long life and welfare. His chief queen was Citrasen’s daughter Cinta, unrivalled in devotion to her husband and in beauty.

Once in the abode of the gods Lakshmi Devi said to Shanaishcar, “Look, I am the chief in the universe because everyone in the three worlds desires me. Can you say that even by mistake someone takes your name? Your sight, even your shadow, is the cause of all types of misfortune in the world.” Shani was enraged at Lakshmi’s words and said, “If I am not supreme among all and more honoured than you, then why should the three worlds shiver fearing me? You will be a laughing stock by claiming you are the best.”

To settle the dispute, both appeared before Raja Shrivatsa as he was preparing to bathe. Startled and wonder-struck, he greeted them humbly and enquired why they had come. Shani explained the entire matter. Bewildered, the king kept silent for a while. Begging time for a day, he requested them to appear in the court the next day when he would present an answer to the best of his abilities. Blessing him, the gods left.

Thinking and consulting all day long with his ministers and others, Shrivatsa decided not to say anything. In the court two seats were placed: one of gold, another of silver. The golden one was kept to the right of the royal throne and the silver seat to its left. The two gods entered and Lakshmi promptly sat on the golden seat, while Shani sat on the silver one. After a while, Shani asked the king to indicate who was the superior of the two. Softly and humbly Shrivatsa said that how could he as a mere human decide about gods. They themselves had decided their relative greatness. Enraged, biting his lips and red eyes Shani declared that as he had ruined Raja Nala, so would he deprive Shrivatsa of kingdom, happiness and wife. Lakshmi was delighted and left, blessing the king.

Day after day, month after month passed as Shani kept searching for a misstep on Shrivatsa’s part. Once, after bathing the king sat on the throne while the washed off water had not been wiped away. Suddenly a black dog appeared and lapped up that water. The shastras state that water washed off the body if fallen on the ground must immediately be removed, never touched. Moreover if polluted creatures like dogs touch it, the bathed person becomes unclean and loses prosperity. Therefore, the instant Shani spotted this flaw, he saw the right moment had arrived and gleefully entered the king’s body.

By and by the kingdom was overshadowed by ill omens: sudden outbreaks of fire, meteor showers, cloud-less lightning strikes and bloody rainfall at some places; somewhere drought, elsewhere floods. Blights of locusts, insects, rats, birds destroyed crops. By Shani’s wrath, Raja Shrivatsa’s prosperity gradually dwindled away. Wailing and lamentation arose everywhere as lawlessness prevailed. Subjects rebelled against the king. Finding no way out, at the dead of night Shrivatsa fled the land with his wife on foot. Covering a long distance, Shrivatsa and his queen arrived at an enchanting wood whose beauty enraptured them. There they saw a fisherman and, suffering from hunger and thirst, begged him for a single fish. Seeing their divine appearance, the fisherman was stunned. Considering them as divinities in disguise, he gave them some fine fish and pranam-ing them left.

Shrivatsa asked his wife not to spurn the fish begged for as this was their only means of sustenance at present. He told her to roast them for eating. After all, he said, in the past the royal rishi Vishvamitra had begged dog-meat from an untouchable to satisfy his hunger. The queen immediately lit a fire by rubbing dry sticks together and roasted the fish. Sadly she went to wash off the burnt parts in the lake, but when she dipped them in the water, they swam away! As she related the misfortune to the king and he burst out laughing, a skyey voice was heard, “Maharaj! Publicly you demeaned me by giving me an inferior seat in front of everyone and enhanced Lakshmi’s glory by giving her a golden seat. Where is she now? O Shrivatsa! As a judge you had displayed bias and now you suffer its just consequences.” Saying this, invisible Shani vanished.

Amazed, the raja told his beloved wife that it was because of his ill fortune that the roasted fish had swum away and she should not weep, for she was not at fault. Shani was not content having deprived him of kingdom and prosperity and making him a forest-dweller. Shrivatsa pledged that as long as he lived he would never abandon the way of dharma and resort to evil. Plucking fruit from trees and with water from the stream they assuaged their hunger and thirst. With grass and creepers they made a hut at the base of a tree and rested therein. Thus they passed the days.

Finding that fruits were becoming scarce, Raja Shrivatsa left that wood and went to a small village nearby where many woodcutters lived. Impressed by his demeanour, they gave him shelter and honoured his wife. Daily he would go into the forest with them to collect wood and thus eked out a livelihood. The river Kaushiki flowed by that village and once a merchant arrived carrying his goods on a barge which suddenly came to a stop. Shanideva, assuming the form of an old Jain mendicant approached him and said, “Sir, by astrology I am aware of the cause of your boat stopping. When you left home, your wife was busy arranging puja of the nine planets. As you left ignoring that, this crisis has occurred. No worries, however! I will give you the way out. In this village of woodcutters there is a chaste wife. If she touches your boat, it will immediately move as before.”

The merchant went to the village and stated his predicament. The woodcutters agreed and sent their wives to touch the boat. Queen Cinta went too. One by one the women touched the boat but it did not move. Finally when Queen Cinta touched it, it immediately began to flow with the current. Amazed, the wicked merchant thought that such a woman was rare indeed and having her with him would be best. He dragged Cinta aboard his boat. Chinta wailed aloud to no avail. The merchant’s boat vanished along the Kaushiki.

Meanwhile Shrivatsa had returned to his hut and on hearing the entire matter fell senseless. Regaining his senses after a while he ran out of the hut like a madman to the riverbank and without stopping to eat, or drink, or rest, proceeded southwards. Crossing many places, towns, habitations, hills, woods and wildernesses the king reached a splendid grove. As he rested under a huge tree, suddenly the immortal cow Surabhi arrived there and, surprised to see a human being, asked him who he was. Shrivatsa told her everything. Reassuring him, Surabhi asked him to stay in her ashram there as by divine foresight she knew that soon his queen and his lost royal glory would be restored to him.

Shrivatsa obediently stayed there. From the mud from the froth of the milk falling on the ground as Surabhi’s calf Nandini suckled her mother he began making clay bricks. Because of that divine milk the brick turned into gold. Amazed, the king devoted himself to making more and more bricks daily.

One day when he was standing on the bank of the Kaushiki musing on his state a trading vessel arrived. Seeing it, Shrivatsa decided that by taking all the gold bricks elsewhere he could earn a lot by selling them and also seek out his queen. The cunning merchant immediately agreed to his proposal and took Shrivatsa with him on the vessel. After a while the vessel reached the sea and the merchant decided to take all the gold for himself. So he threw Shrivatsa into the sea. It was this same trader who had abducted Cinta and kept her in a room in the vessel. Hearing Shrivatsa outcries, she flung a plank into the waters. Floating on that plank, Shrivatsa landed in the town of Sautipur where a garland-maker named Rambhaabati lived. In rags Shrivatsa arrived at her home and said that while sailing his ship had sunk and he begged shelter from her. Rambhaabati said, “Oh, on seeing you I am reminded of my dead nephew! My heart brims over with affection for you. I will look after you as best as I can. You stay with me.” Shrivatsa, keeping his identity secret, stayed in her home.

Baahudev, the ruler of Sautipur, had only one daughter, fifteen year old Bhadraa who used to pray to Devi Bhagavati daily wanting Shrivatsa for her husband. The day he arrived in that town, Bhagavati appeared before her and said that the one she had been desiring as husband had reached that kingdom and was living in the garland-maker’s home. In a bridegroom-choice ceremony she could garland him herself. The ceremony was announced and Shrivatsa wanting to witness it stood under a tall kadamba tree at one end of the palace. Stunning all assembled royal suitors, the princess garlanded this poorly clad stranger. Raja Baahudev in shame retreated indoors and all the invitees stormed out. The queen could not abandon her daughter and arranged for her and the son-in-law to stay in a building. The king appointed Shrivatsa as tax-collector on the banks of the river from all craft sailing by.

The period of Shani’s evil-eye is twelve years. As this passed, Shrivatsa’s depression ebbed and he found the world delightful again. On a summer noon Shrivatsa was seated on the river-bank when a merchant craft arrived and he recognised the wicked trader who had thrown him into the sea. He seized the ship and had all the gold bricks retrieved, imprisoning the merchant. Hearing this, the king arrived at the spot and found Shrivatsa’s appearance totally changed. He was glowing with beauty and health as Shani’s influence had passed. Shrivatsa declared his identity and past history. Baahudev immediately rescued Cinta from the ship and sentenced the trader to jail for his crimes.

Goddess Lakshmi appeared in the firmament and addressed Baahudev: “O king! Fortunately lovely Bhadraa has been born to you and you have obtained Raja Shrivatsa as son-in-law and been able to have darshan of me. Now go and pass the time happily with daughter and son-in-law.” Saying this, the goddess vanished. Shanaishcar appeared before Shrivatsa and said, “Raja, overcome by anger I have inflicted much suffering upon you. Do not bewail recalling all that. This is the way of the world. Be that as it may, I am granting you a boon that whosoever listens full of bhakti to this holy tale of yours, that person will never suffer from my evil eye.” Shani vanished saying this. All rejoiced and after a while Shrivatsa returned to his kingdom with the permission of Baahudev. By the grace of Lakshmi drought, famine and epidemics all disappeared from his kingdom.

Krishna told Yudhishthir that joy and sorrow were cyclical phenomena in life and like Shrivatsa he should be patient, bear happiness and grief staying on the path of dharma. In time surely the sun of happiness would rise and flood his heart with the waters of joy.

Suta told the group of ascetics that this holy tale of Shrivatsa had first been related to Vishnu by Devi Lakshmi. The Lord of Vaikuntha had recounted it to Indra, he to thousand-headed Ananta and the great sage Durvasa. From Ananta it was spread in the netherworld and by Durvasa among humankind. At the end of Dvapar Yuga, Krishna narrated it to Janamejay’s great grand-uncle Yudhishthir.

***

Parikshit lamented before Shuka that he had dearly hoped to listen to the salvific Bharata Samhita that cleansed all sins, but that was not to be and he was doomed to perdition. Shuka assured him that having heard even parts of Vyas’ Bharata he would gain all the benefits of listening to all of it, as Vyas had declared to him. Rishi Kapil reassured him too and declared that in future his son Janamejay would also be purified of his sins of Brahmin-hatred and incomplete snake-sacrifice by listening to the entire Bharata Samhita from Vaishampaayan at the behest of Vyas.

Shukadeva resumed the tale of Dandi. The Avanti ruler was bewildered. Seeing him weeping and lamenting like a child, not knowing what to do the mare spoke to him in human speech, “Master, why weep thus? It is women who weep and lament in danger. Control yourself and think what should be done. It is not proper for the intelligent to waste time in vain. I had warned you earlier but blinded by arrogance you did not pay heed. Now you will definitely have to suffer the consequences of your actions. O Raja! My state is like yours. I will never be able to live without you, nor do I wish to. It is not possible to bear the suffering of this sinful mortal world. Alas, what misery has the maha-ascetic, wrathful Durvasa wrought upon me! He pitied me not—orphaned, helpless and weak. A dweller of Svarga I have to suffer torture in the mortal world. What need have I to live? Therefore, raja, see where the Bhagirathi flows fast! Let us surrender our lives to her and put an end to all suffering. I see no alternative to this. By the grace of this heavenly river so many great sinners have attained supreme salvation.”

***

The Tale of Harisharma

The mare then recounted to Dandi a marvel she had witnessed once when returning from the abode of the moon in the morning, passing over the river Mandakini. She saw a hawk carrying a baby bird in its beak. The chick fell from its beak into the sacred river and at once was transformed into a divine form who was taken by envoys of Vishnu on a celestial aircraft to Vaikuntha. Therefore, the mare urged, the two of them should also put an end to their suffering and attain salvation in the same manner, although committing suicide was a grave sin and she might have to undergo unbearable pain like the Brahman Harisharma.

Dandi begged the mare to recount what had happened to Harisharma. The mare said that in the past a Brahman Dvijahari used to live in the town of Karnaat. He tried his best to educate his son Harisharma but the boy got addicted to wickedness and after his parents’ death lived by robbing others. Inevitably the king of Karnaat exiled him. Roaming many lands Harisharma became thin and weak from suffering. Unable to bear this any further, he committed suicide by leaping into a pond. Because of that sin he had to live on a silk-cotton tree for a long time as a Brahman-demon. Therefore, said the mare, they might also suffer a fate like Harisharma, but was determined to die as no other way was visible.

***

Agreeing to her proposal, Dandi prayed to Ganga and with his beloved mare stepped into the river. Both of them bathed in its waters and wishing to die stepped into the river up to their necks. Both banks of the river got crowded with curious onlookers. In the firmament celestial beings gathered to watch. At that time Vaasudev’s beloved sister, Arjun’s beloved wife, Subhadraa fatefully arrived to bathe. Moved to compassion by the sight, she enquired from Dandi and, having heard everything, without hesitation said, “O Raja! Discard all fear! Even at the cost of my life I will save you. Abandon your decision to commit suicide and come with me. I am of your opposing side, Vaasudev’s sister, Subhadraa by name. You might not trust me, being of your opponent’s camp, but recall the example of Vibhishan. Just belonging to the enemy’s camp does not make one untrustworthy and worthless.”

Hearing this, Dandi’s heart was soothed somewhat. Giving up the decision to die he followed Subhadraa who brought them with all respect to her home and provided shelter. For his protection she approached Dhananjay. Hearing everything Parth was thunderstruck and, smarting like one whipped, full of rage said excitedly, “What is this terrible deed you have done! Maha-mighty Shri Krishna to punish Dandi, having consulted me, has despatched hundreds of messengers to every land, town, village to seek him out. Know that I too am one of them. Shame on so independent a wife as you! Go, do not hope for any favour from me!”

Silently Subhadraa left and went to Vrikodar and humbly recounting everything begged him to say whether the Avanti king would be given refuge or not. Bheem said, “Do you not know that Vaasudev is like our very soul? Therefore, only after telling us should you have offered shelter to Dandi. You belong to a weak sex, unaware of consequences. That is why in this case you have displayed independence and acted wrongly. Woman’s duty is to act after taking the husband’s permission, or in his absence that of father or son. Be that as it may, breaking a promise is counted as a grievous sin. I do not wish to incur that great sin. My nature is to keep my promise. That is why Shri Krishna loves me so much. Therefore, he will surely love me for this work too. Therefore, Raja Dandi hereby receives refuge. Be at peace and return to your quarters! I am warning you never to behave in future in this foolish, rash manner. Inform Arjun of my words.”

Summoning Dandi, mighty Bheemsen addressed him respectfully: “O king, I trust you are well? I am meeting you after a long while. Be that as it may, regarding this as your own home stay here without any doubt.” Reassured by Vrikodar’s words, Dandi replied humbly, “Great Sir! It is not novel, surprising or astonishing that generous-hearted mahatmas like you should behave frankly like close relatives. I pray to God that people may face such intimacy in birth after birth and gain such holy company. Interacting with sadhus like you is a prime happiness of this world. Therefore, today I have obtained incomparable store of happiness.”

At such time Yudhishthir’s messenger arrived and with joined palms submitted to Bheem, “O valiant one, it is the Lord’s command to be present before him at once!” Mighty Bheem arose immediately and reassuring the Avanti Raja and asking him to remain there went to Yudhishthir. He saw the loving mother Kunti seated with her four sons like the Mother of the Vedas with Rig, Sama, Yajur and Atharva, or Shanti Devi herself with Dharma, Artha, Kama and Moksha. Maha-intelligent Vrikodar appeared among them like Ananda (bliss) embodied. In the Kuru clan the five brothers and Kunti were like the five senses and Prakriti. The five brothers were separate merely in body but one in heart, mind and soul. Having greeted them and being greeted in return, Bheemsen sat and awaited Yudhishthir’s commands, knowing that it must be about Raja Dandi.

Kunti said to Vrikodar, “Before taking action, whether good or bad, one must examine its pros and cons. Without such examination one should not take any decision suddenly—even if good—whereby in future one might repent or suffer remorse. You have not done well by granting refuge to Dandi. Subhadraa is a woman and giving a promise at a woman’s word without considering does not befit a man. It is well known that woman’s intelligence causes chaos. It is true that to protect refugees is Kshatriya dharma. It is true indeed that keeping a promise is the supreme dharma of every person. However, it is also supreme dharma to act upon all this after due consideration. Specially, one who is an intimate friend and support, always a well-wisher, ever our refuge and the only salvation, who is dearer than the soul itself, to maintain loving relationship with him is the supreme dharma. Such is Shri Krishna for us. How often you have advised others in similar fashion. Then today why did you act contrary to that? Are you deluded as sometimes even rishis are? That is why I am giving you advice. Therefore, I advise you to discard Dandi, or surrender the mare to Krishna. Otherwise there will be great destruction, there is no doubt. You are highly intelligent, so do not engage in dispute with one’s own. It is well known that Lanka’s ruler Dashaanan was destroyed with his clan by quarrelling with his intimate well-wisher Vibhishan. I pray to God that because of your error we do not fall in similar danger.”

Maha-intelligent Vrikodar replied in sweet words to his mother, bowing his head to her advice, but begged her to hear why he had granted refuge to Dandi lest, like the guru of the celestials, she face embarrassment on speaking without knowing the reasons. “The shastras prescribe,” said he, “that a promise must be kept; not to do so is death. Even imperilling one’s own life another must be helped. None as pure and wise as Shri Krishna exists and he would never consent to my abandoning a refugee. Moreover, he is dearer to us than life itself and so are we to him. People truly say that between the Paandavs and Yaadavs there is no difference. Therefore, when he is willing to even give up his life for us, then it is not strange that he should give up a mere mare for us. I also believe that Subhadraa is supremely blessed and much loved by Krishna. Definitely her word will be honoured. Considering all this, whether I can grant shelter to Dandi without waiting for you all or not, you command.”

The son of Dharma said, “Brother, what you said is true. However, in view of the type of relationship we have with Vaasudev, by not give up the mare the Avanti Raja seems to have acted against us—this is what we should realise. So far as I know, no error or delusion exists in the lord of Yadus definitely. In such conditions, it is impossible to consider King Dandi as wholly free from fault.”

Maha-intelligent Vrikodar said, “Dharmaraj! Well, I accept that by acting against Vaasudev the Avanti king has also acted against us, for between Vaasudev and Paandavs there is no distinction. But it should also be considered that when Dandi took refuge with us he also took refuge with Vaasudev. To forgive the offender is the true expiation of his sin. Should he again come to seek shelter, he is fit to be forgiven a hundred times. This is the quality of the best of men like Shri Krishna and his view too. To tell you that is unnecessary. Considering everything from the beginning to the end in this manner, I have granted Dandi refuge.”

Dharmaraj said, “Brother, you have done well. But consider whether before granting refuge to Dandi was it not proper to seek his opinion in person or by sending someone to Shri Krishna when he is capable of comprehending everything about us? At least we should have been consulted. One should act thinking through the consequences. You are intelligent, wise, aware of policy and know the shastras. To say more to you is needless.”

In the meantime Shri Krishna and Rukmini’s son Kama-deva (Pradyumna) arrived as commanded by his father. He looked just as enchanting as his father, winning all hearts. Delighted, Kunti stood up and embraced Madan, shedding tears. Anxiously she enquired after the welfare of her sole relatives, specially Vaasudev. The Paandavs also enquired similarly after greeting him warmly. Responded appropriately, Rukmini’s son down.

Yudhishthir then said to him, “Despite being aware that between Vaasudev and us there is no distinction, Dandi the ruler of Avanti has taken refuge with us and blessed Subhadraa knowing everything has given him her word of protection. Although all this has occurred without our knowledge, it is duty to protect the refugee. Therefore, we have not stopped Vrikodar in this matter. Moreover, we know that even if we commit a thousand offences knowingly, Paandav-loving Bhagwan lord of Yaadavs will surely pardon us. Considering all this, we have decided to go to Dwarka in person to tell Shri Krishna. It is good that you have arrived at that very juncture. Now act as you consider proper.”

Rukmini’s son replied addressing Kunti, “Today I have not come as a close relative or friend. Today a great burden has been laid upon me which I did not wish to carry here, but I have had to. I have been unable to bring anything dear to you, as my mother did not agree, although father had given many things for each of you. I do not have permission to tarry even a moment. Hear the reason why. By acting illegally, Dandi, Avanti’s raja, has offended my father Vaasudev. Father is firmly pledged to punish him properly, which you are not unaware of. All of you have also agreed to this. Despite that the middle Paandav gave his word to protect the Avanti lord—is this proper policy, rightful, sanctioned by dharma or even logical? Be that as it may, if you wish so much to protect Dandi, then at least on the basis of intimate relations, at first even through a messenger this should somehow have been intimated to my father. Lord of Yaadavs Vaasudev would surely have forgiven Raja Avanti because of the sincere relationship, friendship and heartfelt love that exist with you even if you had violated its norms. To behave knowingly otherwise harms the friendship, that is not unknown to you. Be that as it may, all this is irrelevant now. My father Vaasudev’s core message is this: he has declared war against you, therefore get prepared for battle quickly. The moment I return to Dwarka the Yaadav army will attack you like a stormy sea undoubtedly. We have tried to plead with him in many ways, but in Vaasudev’s view breaking a pledge is maha-sin. Thus both sides are committed to honour their promises. There is no easy way out but war. Therefore, now do as you consider proper.”

Having said this, Rukmini’s son Kamadeva did not wait for a reply. He stood up at once and left the hall to return immediately to Dwarka as ordered by his father, not even waiting to take formal leave. Seeing him leave like a stranger, Kunti and the Paandavs became depressed like a lotus at the onset of winter, just as they had bloomed joyously at his sun-like arrival. None uttered a word for some time, unable to decide what should be done, staring at each other’s faces in dismay.

Unable to remain still, Paandav-mother Kunti rose and rushed after Madan who had anticipated that she would not stay still (since women act without thinking of consequences) and was walking away very slowly. So Kunti had no difficulty in stepping forward and lovingly catching hold of Rukmini’s son firmly with both her hands. How indescribable is the might of divine maya which encircles and binds all creation! None can escape it. As bhakti’s devoted slave, Krishna’s son Kama-deva honoured elders sincerely, full of bhakti for the Paandav-mother like a worshipped devi. Therefore he was unable to extricate himself from her embrace and could not advance even a step. Kunti’s tears drenched his breast. Then Kunti broke her silence and said, “Dear one, without telling me where are you going? Has Vaasudev told you to behave in this way without bhakti and affection? Or is that the advice of your cruel-hearted mother? No, that cannot be! Perhaps you are behaving thus overcome by childish, whimsical inclinations. However, you will not be able to leave now; I will not let go of you by any means. At this instant I am despatching my chief envoy to Vaasudev. You stay here! My messenger will tell Krishna that I myself have granted shelter to the Avanti ruler. Or, right now I will go myself with family to Dwarka and see with whom Vaasudev will fight. Should conflict arise finally, you will have to help us. Look, whenever any type of danger has occurred, Bhagwan Vaasudev at once helps us. It is he whom we call upon when fallen into danger and beg him alone to save us from calamity. Between him and you there is no difference. Therefore, in the danger besetting us it is you who will have to be our support. Besides you in this world there is no friend in danger we can turn to.”

Rukmini’s son Kama-deva replied to her politely in sweet speech, “Devi, your wish will bear fruit; your heart’s desire will be fulfilled I have no doubt. Vaasudev himself will be your support. That Shri Krishna is the support and friend of Paandavs is well-known in the three worlds, therefore why are you disturbed and anxious? People’s minds get distracted in danger—is your state also like that? Or are you putting me to a test? Devi, just as water never becomes fire and fire never turns into water, so God does never cause harm to anyone. Have you forgotten that? Has it ever been seen or heard that Vaasudev has anywhere caused harm of any type to anyone? Even if he causes harm it is transformed into a great favour. Whatever he does is for welfare. Those who arefortunately able to become aware of the true form of God Krishna, it is they who are capable of comprehending all this. What more shall I say? Attend to what I say in brief.

“Mother Rukmini-devi had said to my father that everyone in the three worlds believed that he would even destroy himself but never go against the Paandavs. Paandav-destruction was absolutely impossible for him. Therefore he must reveal to her what his intentions were behind declaring war against them, for the consequences of all his acts were always for welfare. If he did not do so, she would not permit Kama-deva to go to the Paandavs. Smiling, father Vaasudev told my mother that he could never keep anything secret from her for she was his second heart. She had correctly surmised that whatever he did was for the good of people. The battle he had announced was for bringing about the future welfare of the Paandavs. He said, ‘For accomplishing a task there were two ways: one by force; the other by strategy. Of these the second path is superior and adopted by the intelligent, whereas the first is beastly and the way of beasts of prey. In future the Paandavs would have to accomplish many grave tasks like killing terrible foes and seizing kingdoms. By displaying one’s own prowess in public, enemies can be overawed and the desired goal attained. With the mare as excuse, joining with the devas I will of my own accord be defeated by the Paandavs in battle. Thereby the Paandav’s unique worldwide glory will be established. Their enemies will not be capable of rising up against them suddenly. Many foes will accept their overlordship out of fear, without battle. Just hearing the name of the rakshasa Dashaanan many would accept his mastery on their own. It is not necessary to strike with the vajra; merely on hearing its crack people in the three worlds shudder. O auspicious lady! For accomplishing the task I have adopted such a strategy and it is for this reason that I have declared war. Do not worry!’

“When father stopped speaking, my mother’s delight was boundless. She loves and honours you even more than me. Her affection and bhakti are genuine, sincere. Therefore, be assured. Your sons will be world-conquerors undoubtedly. Vaasudev is God himself, as you know. So remember that God never causes misfortune.”

Reassuring Kunti thus, Krishna’s son Madan then left. Kunti was unable to stop him. Pursuing him as best as she could, finally she stood at one place, waiting till Rukmini’s son vanished out of sight, gazing fixedly like a statue, as if seeing him even when he was beyond sight. Such was her love for Vaasudev and his kith and kin. Later, distracted, like one mad and helpless, she approached the royal road and then came to her senses. Then slowly she turned towards her residence and gradually, like rain-laden clouds, walked musing, “Madan’s words are true indeed. God never does what is bad; whatever he does is for good.”

The lord of Yadus having appointed his son Madan for the aforesaid task as messenger immediately proclaimed hostilities. On receiving his orders the three-worlds-conquering Narayani Army left for battle at once. Shaamba, Aniruddha, Gada, Shaaran, Saatyaki, Haardikya, Akrur and other Yadu warriors are renowned maha-heroes on earth of unrivalled might. Each left with his troops equipped for battle. The earth filled with horses, elephants, chariots and infantry. The sky was filled with pennants, banners, crowns, plumes and the quarters resounded with neighing, trumpeting, roars, shouts and the clattering of chariots. All apprehended that untimely dissolution was impending.

On Mount Kailas deva-of-devas Pike-wielder Shiva could not remain still any more. That deva-of-devas Vaasudev, upon whose feet he meditated in his heart day and night, he had commanded. Therefore, he too arrived to fight against the Paandavs. His hand held the three-worlds-shattering great pike, accompanied by innumerable spirits, ghosts and demi-gods. Their appearance was very terrifying, highly virulent by nature. Some had faces of horses, elephants, tigers, lions, cows, deer, leopards, with one mouth, many mouths, one foot, two feet, three feet, four feet and more. Some were cripples, some dwarfs, some sick, some lame, some naked, some pot-bellied, some with sunken bellies.

Thereafter lotus-born Brahma with prayer-beads and Shachi’s husband the lord of devas with Jayanta, the clouds Samvartta, Aavartta etc. with their mighty, huge attendants arrived there. Lord of waters Varuna with thousands of rivers, lakes and seas arrived. Powerful, heroic lord of Yakshas Kuber arrived with variously dressed, triple-headed hordes of Yakshas. Dharmaraj Yama himself on his buffalo mount with Mrityu-Death, Kaal-Time and other followers came. With him were two chief warriors, terrible Jvar-fever and Maha-Jvar along with the general of all, Maha-Mrityu. Rakshasa raja Vibhishan and leader of apes Hanuman also arrived at the city of Yadus surrounded by innumerable troops. Whichever maha-warrior there was in the three worlds, everyone arrived in the city of Dwarka the moment they received the command of Krishna the lord of Dwarka to fight with the Paandavs.

Seeing the assembled warriors, the heart of Krishna the supreme strategist brimmed over with happiness. He thought to himself, “Today the supremacy and total victory of my most beloved Paandavs will be established in the three worlds, for today all the heroes of the three-worlds will be defeated by them.” Musing thus he arrived for battle near the place where the Paandavs were, the quarters and the sky echoing with the dreadful tumult of the troops. Without wasting an instant he messaged the Paandavs, “I have arrived with troops. Either hand Dandi over, or prepare for war. Other than these alternatives, I see no way for your welfare.”

Kama-deva while leaving had prohibited Kunti from revealing to others the secret he had conveyed to her. Therefore, without saying anything to her sons Kunti entered her chamber. Dharma’s son Yudhishthir, knowing that battle was inevitable, addressing his maha-heroic four brothers said, “What should be done now?” Kiriti (Arjun) said, “Nothing is to be done. Vaasudev will act.” Vrikodar said, “It is battle that is definitely duty. Where dharma is, victory is —if this be true then the always-devoted-to-dharma Paandavs will definitely be victorious. This I believe without any doubt. My mind is made up to fight.” Nakul and Sahadev said nothing, remaining silent. Again Yudhishthir said to Bheemsen, “Brother Bheem, you have no allies, no wealth, no troops and no general too. How will you fight? Particularly, battling Krishna on whose side are all the devas and heroes of the three worlds! Even if they were not, there is no loss, for by himself he is the devas and heroes of the three worlds. It is not as if you do not know that.”

Laughing, Vrikodar said, “I do not expect any other ally or wealth. With dharma alone as ally and wealth I will fight alone.” Then Dhananjay said politely, “If war is the settled decision then in my opinion Duryodhan’s help should be sought.” Noble Nakul opposing these unwelcome words of Arjun said, “That can never be. He is our constant foe. Suicide is preferable to praying for help from him.” Then Sahadev said, “The person who can fight with Shri Krishna, it is not impossible for him to take Duryodhan’s help. That type of person is also capable of suicide. In brief, I do not like any of your ideas. I will not fight, will not be on any side. I will only sit beside mother Kunti.”

As the brothers argued thus Yudhishthir said, “At this time disputing is not proper. Calm down! Let me ask mother. Whatever she permits we will do.” Saying this, Yudhishthir went to the mother and reporting everything said, “Mother, those who have found so wise a mother as you and as their supreme well-wisher, what worry can they have? Now you decide what we should do.”

Kunti said, “Just as agnates should be regarded as born foes, so too sometimes they should be considered as the best friends. Therefore, send an envoy to Duryodhan asking for his help. In danger even poison is amrita, and again amrita can become poison.”

Dharmaraj Yudhishthir heeding the mother’s advice and command immediately sent an envoy to Duryodhan. Hearing the entire matter from the envoy Dhritarashtra’s son asked the advice of Beeshm and others in the court. First wicked and cunning Shakuni said, “Fortunately the right time has come. Opposing Krishna the Paandavs will have to perish. Therefore, joining Krishna’s side you should destroy the enemy. What is more delightful and lucky than the enemy being destroyed by the hand of another?”

Hearing this rage flooded Vidur’s heart. Angrily he said, “Though washed a hundred times the blackness of coal is not removed. A snake can never disgorge nectar, only venom. You too are the same. Habitually you are wicked and you have spoken as is your nature. Your advice is not at all just or logical. The Paandavs are brothers and agnates. To take their side in danger is duty by all means, specially in such circumstances. If you do not help, that is your matter. But we have to tender proper and just advice. That is why I am saying this: it is protecting the refugee that is the dharma of Kshatriyas.”

Vidur’s words touched Duryodhan’s heart. He felt that helping the Paandavs was the best option and, ordering the troops to prepare, he himself made ready with Beeshm and other Kuru heroes. Soon Duryodhan set out for battle with a four-fold army. The ten directions echoed with the sound of drums, resounding with the trumpeting of elephant columns, the neighing of cavalry and the shouts of troops. His tributary chiefs also rushed to join him. The Paandavs too got ready for battle and left to face the Yaadav army. Hidimba’s son the maha-hero Ghatotcach began to accompany them like a mobile mountain. It seemed as if five lions were exiting a mountain cave with their only cub; or that Brahma, Vishnu, Rudra, Ganesh and Surya the five gods had descended upon earth from heaven with mighty Karttikeya.

Kurukshetra, sacred in the three worlds, was designated as the field of battle. Soon armies of both sides arrived at that holy place, terrifying the world with their tumult, the ten directions flashing with the reflections from their weapons, the earth shuddering from the weight of their steps, the quarters filled with the sound of their shouts. That gods, demons, gandharvas and others would fight with men, such an unprecedented, unheard of event none had ever dreamt or thought of even by mistake. Therefore, with all the heroes of the three worlds being gathered there a novel, marvellous scene was observed on the field of Kurukshetra.

As the armed troops awaited the command, the Kuru patriarch Beeshm decided to despatch a messenger to Vaasudev as propriety and bounden duty demanded. When everyone approved of that, maha-minded Vidur himself presented himself before Krishna as envoy of the Paandavs. Greeted by Krishna as proper, Vidur took a seat having saluted him and said, “Bhagwan, your sport is wondrously various and baffling to people in general. Why you do anything at anytime is known to you alone and none else. Therefore, how will I make out what the result will be of this Yaadav-Paandav war? Be that as it may, to ordinary people of low intelligence like us this war does not seem to be just, appropriate and logical. Those who are always followers, seeking shelter and obedient, those very Paandavs you are embarking against. To see, hear and speak of it is disgusting. Therefore, to refrain from this war appears to be the best in every way.”

Then laughing Krishna said, “O maha-minded! It will be even as you have said. Do you not know I always favour my followers, am defeated by my bhaktas and controlled by them? Therefore, fear not! Today too I will be defeated by the Paandavs. Go quickly and proclaim hostilities!”

As Krishna was speaking thus with Vidur, Devi Kunti arrived there. Seeing her, Krishna arose and the Paandav mother lovingly grasped him by the hand. Comprehending her intention, Vaasudev said addressing her, “Devi, grant blessings that today the Paandavs gain the glory of victory and I with my army be defeated by them. Perhaps from Pradyumna you have become aware of my intention. Therefore, depart free from fear, being assured.”

Kunti said, “Child, women by nature are fickle. Even having seen and heard, because of that fickleness I am confused, anxious and distressed. What more can I say when terrible dangers can be overcome by singing and remembering your name! Specially, you are well-wisher of the Paandavs, never think or do their ill. Therefore, whatever you think is proper and good, do that.”

Saying this, in great distress Kunti left there with Vidur. Vidur having escorted her to her place went to the battlefield and conveying Vaasudev’s intentions to Beeshm and others said, “You all prepare for war. Vaasudev does not wish to make a treaty.”

As Vidur spoke thus, from the Yaadav side tumultuous roars filled all sides splitting mountain caves and the sounds of drums beaten loudly echoed. That terrible sound terrified cowards and inspired the brave, distressing peaceful well-wishers. Battle-mad elephants and horses shitting and pissing reared up trumpeting and neighing. Then momentarily the battlefield shook and echoed, the sea became tumultuous, hills moved with landslides and the sky seemed to expand.

Krishna’s son Kama understanding that this was the right time, released the unique mesmerising missile from his bow to see the fun. Instantly, all on the battlefield were stunned; eyelids drooping, bewildered. Beeshm, Dron and other heroes all were at a loss, deprived of movement, standing still at one spot like statues. No one could comprehend the reason for such a sudden mishap.

Thereafter, omniscient Shri Krishna having permitted his son to withdraw the mesmerising missile, Pradyumna did so at once. Then the opponents being able to understand waxed wild with rage and all engaged in battle together. Both sides, mortal and immortal, were equal in weaponry and vigour. First, deva-of-devas the Pike-wielder himself engaged in battle with Beeshm. Seeing lord of spirits Mahadeva fighting, his attendant hordes of varied appearances leapt into war full of pride and rage. Jahnu’s daughter Ganga, from within Mahadeva’s matted locks, with her pure glances snatched the strength of the spirit-hordes and bolstered the power of the Kuru troops to encourage her son Beeshm’s enthusiasm. Seeing that, Bhagwan Maheshvar glancing at his followers excited their energy so that they madly engaged in destroying the Kuru troops. Then the Kuru soldiers, distressed by their attacks, began to flee in all directions. Yadu-lord Shri Krishna seeing the warriors on the Paandav side bewildered and fleeing, immediately held back his own battling warriors. Then, troubled by sun-like Beeshm’s blazing onslaught, the triple-eyed conqueror of worlds grasped his terrible world-annihilating great pike.

Simultaneously, terrific duels took place between mighty Bheem and Baladev, Karn and Kama, Arjun and Skanda, Dron and Shri Krishna, Duryodhan and Indra, Shishupal and Shaamba, Dantavakra and Satyavaan and Kama’s son Aniruddha with Jaraasandh and Ghatotkach.

The deva army with great energy and battle-ferocity, in great rage with great force began to decimate the Kuru army using celestial weapons. Thick clouds of dust raised by arrows, dense darkness and blinding rays of light appearing seemed to be ending the world. The sea and the earth shook repeatedly, echoing with the roars of warriors of both sides. The clash of arrow with arrow, sword with sword, club with club, spear with spear kept growing more and more fierce. The deva army teeming with elephants, horses and chariots tinkling with thousands of bells, mighty like blue clouds, engaged in terrible battle with the armed Kuru troops. The Paandav soldiers almost mad with anger began to trouble the deva troops showering them with pikes, swords, spears, javelins and arrows with golden fletches. Yaadav soldiers began to be slain on elephant-and-horse-back and fell terrified. Soon the battlefield became filled with splintered chariots, sundered elephants, horses and warriors’ limbs.

As a fish delighted on finding fresh water leaps into its depths, so maha-hero Arjun entered into the ocean of deva troops to fight Karttikeya. He mused, “The devas entered the battlefield with troops to assist Vaasudev and are immortal. Therefore, by weapons I will return them to the place they have come from.” Thinking thus, the leonine hero Parth shot the wind-missile. Like robbers that are bound hand-and-foot by the State, the greatest hero of the three worlds Karttikeya too, being placed in his own abode by Arjun’s wind-missile, was surprised, startled and stunned. Great Skanda was so overcome with shame and dispirited that he became incapable of entering the battlefield again.

Elsewhere, seeing the battle-skill of Dronacharya, Karn, Vrikodar, Shishupal, Dantavakra, Jaraasandh and mountainous Ghatotkach there was no end to the amazement of Kamadeva, the lord of devas Indra, Shaamba, Satyavaan, Aniruddha and other heroes on the Yaadav side. None could make out when the Paandav maha-heroes strung arrows on bows, released them or drew arrows from quivers They could only see opponents falling on the battlefield, crushed, decimated.

When the dispirited Yaadav army and many heroes began to flee, then the lord of waters Varuna-deva enraged entered the war surrounded by all rivers, lakes, ponds and wells. By his mighty current, the battlefield was flooded and elephants, chariots with riders and drivers, soldiers floated helplessly. By Vaasudev’s maya soon that too was ended. A little later, the lord of waters too retreated being defeated by the Paandavs.

By Vaasudev’s maya, bewildered by his discus and the variety of his sport, almost blinded, senseless, the deva and Yaadav armies, like spellbound pythons or thunder-struck trees or entranced creatures, fell motionless, bereft of strength and spirit. Therefore, the Paandavs won victory and the Yaadav side was defeated. What is more, Bhagwan Vaasudev was defeated by Dronacharya, the deva-of-devas by Kuru-lord Bheeshm, the lord of devas Indra by Duryodhan, Varuna-deva by Nakul, Yama by Kripacharya, Vayu-the-Wind by Yudhishthir, Kama by Karn, Baladev by Bheem, Shaamba by Shishupal, Satyavaan by Dantavakra, Aniruddha by Jaraasandh, the general of devas, six-headed Karttikeya, by Dhananjay and Saatyaki by Sahadev. Similarly, other heroes on the Yaadav side were also defeated by the great heroes on the Paandav side.

What can be more shameful, disgusting, laughable and regrettable than the celestial host being defeated by humans! Thinking thus, the devas’ hearts filled with rage, hatred, jealousy and outrage all together. Like ghee-fed fire, spurned serpents and storm-tossed seas, with redoubled enthusiasm they appeared again for war. Grandsire Brahma and the lord of death Yama had been defeated by Shaalva and the Paandav Yudhishthir. Both of them again with redoubled spirit, prowess and enthusiasm rushed into battle. Again the devas by beat of drum announced war. The maha-hero, Parvati’s son youthful Kumar again with full force and enthusiasm entered the battlefield with his troops. This time the devas, determined to destroy the foe, took up their special weapons. Brahma’s rosary, Vishnu’s discus, the Pike-wielder’s pike, Karttikeya’s dart, Varuna’s noose, Indra’s vajra and the lord of death Yamaraj’s deadly staff, these seven thunderbolts assembled. By the energy and the terrible sound of these seven vajras heaven and hell were filled, the earth shook and the three worlds were terrified.

Meanwhile, as a lake is not beauteous without lotuses, the sky is dull without the moon and the serpent plain without its gem, so was the state of the city of the immortals without Urvashi for so very long. That what is Svarga’s should return there and Svarga’s beauty reside in Svarga, this was the innermost desire of the devas, devis and specially of the raja of the devas. So that this wish could be fulfilled without delay the deva-host was constantly worried, striving to accomplish that and determined to find out the means for that. Mare-turned Urvashi too unable to bear the torture of the mortal world was constantly meditating upon Devi Bhagavati’s lotus feet hoping for salvation. Cursed by the rishi, when Urvashi had tearfully pleaded with the maha-ascetic Durvasa, he had said, “In time, upon earth the moment the eight vajras assemble your curse will be lifted.” Now seeing that seven vajras had assembled, lovely Urvashi concentratedly began to dhyana of Devi Bhagavati and paean her.

As the miser is the slave of wealth, the greedy of food and the voluptuary of desire, so devas are overcome by bhakti. Devi Maheshvari always regarded Urvashi with affection. Seeing that without Urvashi the world of apsaras had become bereft of splendour, dull and sorrowful like Lakshmi-less Vaikuntha, Gayatri-less Brahman homes and dancing halls without lights, her heart was already pained with regret and she was thinking how to free her from the curse and fetch her to the celestials’ abode. In the meantime, the paeaning of the best-of-apsaras Urvashi agitated her heart even more. She also heard from her attendant Vijayaa about the defeat of the deva-host. Then unable to stay still any more, realising that this was the proper moment to accomplish the task, Devi Haimavati—creation-preservation-destruction-doer, demon-destroyer, sin-remover—immediately appeared on that dreadful battlefield to fulfil Bhagwan Vaasudev’s aim and remove Urvashi’s curse.

Descending on the battlefield in the form of the war-goddess Chandikaa, stunning and bewildering the ten directions with resounding loud laughter, she stood amidst the deva-host. Seeing her appear in the battlefield, the heart of Urvashi-turned-mare danced with delight. The seven devas mentioned above hoping to gain victory, pranam-ing at the Devi’s feet, flourishing their seven vajras stood for destroying the Paandavs.

Then the dissipator of all maya, the severer of bonds of being, the presiding deity of maya Mahamaya shaking the three worlds with her roars, raised her own sword. Upon all the eight vajras appearing simultaneously before her eyes, the curse laid upon Urvashi by the rishi was removed. Abandoning the mare’s form, assuming her own self she fell at Devi Bhagavati’s feet and with palms joined together submitted, “Mother! Restrain your rage! Having brought creation into being, it is not proper to destroy it. If along with these seven weapons of the devas your infallible sword is let loose then, let alone the Paandav army, the three worlds will sink into oblivion forever. Therefore, be pleased and withdraw this terrible form! By your grace, after so long I have achieved liberation from the rishi’s curse.”

Saying this, lovely Urvashi pranam-ing the Devi again, rose into the firmament. From the sky flowers rained down in abundance covering the battlefield. Joyous beat of drums sounded delighting the ears of all. The Devi, too, pleased, vanished from there at once.

While leaving, Urvashi addressing Raja Dandi said, “Maharaj, do not be deluded by the world’s vain maya. Thinking the evanescent world to be eternal, thinking the delight of luxury is the essence of the world, erroneously overcome by delusion being confused by maya, you have suffered so much pain, suffering and humiliation for so long. Now everything is clear. Wherever there are possessions there is danger, where there is birth there is death and where there is union there is separation. Realising this, by the yoga of knowledge, intelligence and discrimination steady the atman. Instead of feeling worry, grief or sorrow for me, fix your consciousness on the feet of the God of all, the atman of all, Shri Hari. Only then will you be happy in endless joy and attain refuge in the all-sins-removing lap of that Lord.” Saying this, when Urvashi departed the Avanti raja remained with head bowed for a time like one entranced, bewildered, startled and stunned. Controlling the mind’s movement by the power of intelligence, discrimination and knowledge, he became firm.

Seeing such an unprecedented, unthinkable and unexpected event the devas, Paandavs and Yaadavs were amazed beyond all bounds. By the grace of Bhagwan Vaasudev and his maya the war was halted. By the Yaadav-lord Krishna’s infinite maya the Paandavs won victory. The three worlds echoed with their majesty, glory and prowess. Thereafter, greeting each another pleasantly, both parties returned to their own places with their attendants.

Shuka informed Parikshit that he was actually the principal courtier of the celestial court, a Gandharva named Vidyaadhar. Like Urvashi, he was an incomparable gem of the court of the immortals. In his absence Indra the lord of devas was dull and dispirited like the dimmed moon. The time for the end of his curse had approached. Resorting to yoga he ought to abandon this temporary mortal frame and proceed to Svarga soon, particularly as destructive, sinful, invincible Kali Yuga was spreading over the world. Yet, he said, Veda Vyas had declared that while practising dharma through ascesis, abstinence or prayers bears fruit in ten years in the Satya Yuga, in one year in the Treta Yuga and in one month in the Dvapara Yuga it fructifies in just one day-and-night in the Kali Yuga. Therefore, the Kali Yuga is the best. The benefit that accrues in the Satya Yuga by taking considerable pains through dhyana, by diverse yajnas in the Treta and through varied pujas in the Dvapara is achieved in the Kali Yuga merely by chanting the name of Hari and donating without desire, visiting tirthas or even listening to their glory.

Having said this, Shukadeva left Parikshit. On the seventh day Parikshit died after being bitten by Takshaka naga and his soul flashed into the heavens. At that time Janamejay was but a child. The counsellors and the subjects installed him as raja so that the kingdom was not left ruler-less. In due course, marrying the Kashi king Suvarnavarmaa’s daughter Vapushtamaa, Raja Janamejay ruled happily.

Having narrated all this, Lomaharshana’s son Sauti took leave, offering pranam to Shaunak and the other ascetics and, meditating on Hari, left on pilgrimage to tirthas.

***

Conclusion

In his play Girish Ghosh made Bheem the main character and placed the incident at the time when the Paandavs and Duryodhan were assembling their armies for the war. It is Saatyaki who informs Krishna, much to his astonishment and rage (he is not omniscient as in the Dandi Parva), that a spy has found that in the kingdom of Matsya Yudhishthir has granted refuge to Dandi. Instead of Pradyumna it is Saatyaki who is sent to Yudhishthir as Krishna’s envoy. Bheem visits Krishna in Dwarka and begs for death at his hands in a duel, sparing his four brothers. On Krishna’s refusal, Bheem calls him “Great trickster, great cheat, extremely cunning (ati chhal, ati khal, ateeva kutil)” (Act 3, scene 5), a dialogue that became extremely popular among the public. Following advice sent secretly by Krishna, Subhadraa goes at night to a shrine of the Goddess in a dense wood where she obtains her blessing that Dandi will regain his kingdom. Arjun meets Urvashi and assures her of salvation. Seeing them together, the jealous Dandi surrenders to Krishna in Dwarka but is refused as he has not brought the mare. Balaram also joins the battle and is defeated by Bheem. Beeshm defeats Shiva, Karn defeats Indra, Yudhishthir defeats Brahma. Krishna despatches Saatyaki to advise Mahadeva to take up the trident, Brahma the water-pot, Indra the vajra, Varuna the noose, Skanda the spear, Yama his rod, while he himself takes up the discus. As they wield their weapons, Kali (Ghosh calls her Krishna’s mother Katyayani) manifests with raised sword and her yoginis. The curse is lifted with paeans to Kali. By Krishna’s grace all those killed are resurrected.

There is a Telegu myth, whose origins are not clear, about Arjun fighting Krishna which was made into a film in Telegu, Kannada and Tamil, entitled “Krishnarjuna Yuddhamu” in 1963. Here, Arjuna had boasted to Narada that none can make him fight Krishna. Gaya or Chitrasen is the Gandharva king who, is blessed by Brahma with eternal fame. While returning to his kingdom in his aircraft, he spits betel-juice. This falls into the hands of Krishna (or of rishi Gaalav) as he is offering prayers to Surya, the sun god. Infuriated, Krishna swears to kill him (or Gaalav orders Krishna to do so). Terrified, Gaya flees and is advised by Narad to seek refuge with Arjun via Subhadraa who, without ascertaining facts, grants him protection. She then persuades Arjun to protect him so that her promise is honoured. So, Arjuna wages battle with Krishna. To save the earth from dissolution, Shiva appears and stops the duel. Krishna/rishi Gaalav pardons Gaya. This tale parallels the Rama-Hanuman duel over a similar incident that was also made into films in Hindi (1957), Telegu (1975) etc. However, the Dandi Parva is unique in its focus on the eight vajras having to be flourished together for the liberation of Urvashi from her cursed state as a mare.

[Published in KALAKALPA, vol. VII, No.2, 2023, the IGNCA journal of arts]