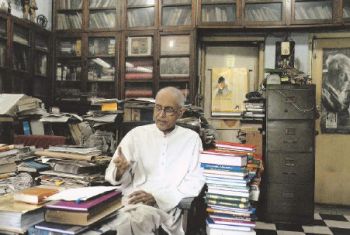

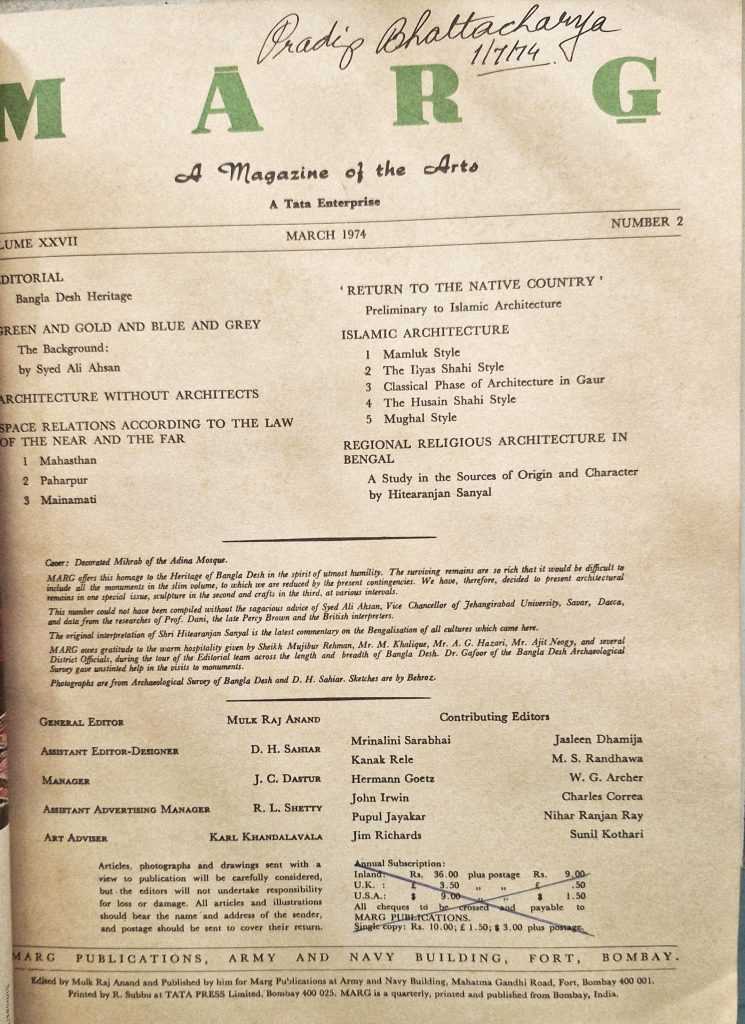

On the evening of 14 April 1972 I met the renowned novelist Dr. Mulk Raj Anand in the bungalow of the District Magistrate, Malda, Mr. S.P. De IAS (1959 batch). I was then Assistant Magistrate and Assistant Collector on training. Anand was accompanied by Miss Dolly Sahiyar, photographer of MARG magazine and Sri Ajit Neogi, President Bangla Academy of Rajshahi. MARG was publishing a feature on Muslim architecture of Bangladesh. I was asked to guide them around the historical monuments.

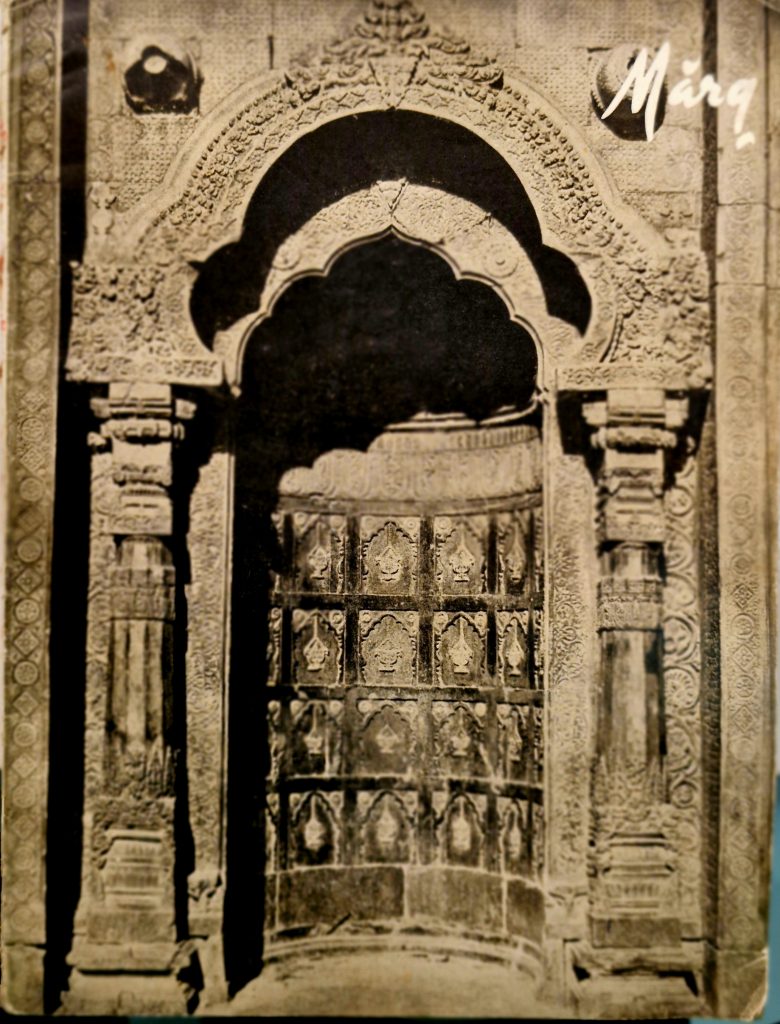

On 15th April from 630 AM I took them around Gour and Pandua for 6 hours. Dr. Anand was in shorts and a brick-red top; very fair, a prominent acquiline nose; white hair streaked with dyed brown. At Adina Masjid the fusion of Hindu and Musim art had created a new Bengali art joining swastika and Muslim petal work. Sudhir Babu pointed out that Muslim petals curved backwards while the Hindu curved inwards. No masjid sports such a vast open-air compound lined with cells typical of a Buddhist monastery. The doorway decorations have Hindu carved panels with faces of deities smashed. Every panel in Adina in the courtyard has a different design.

Then I took Dr. Anand to the Malda Museum which was in poor shape. Entering the museum he shouted aloud, “Arrey! This is a godown of images. Why haven’t you arranged the statues properly according to the timeline? Is there possibility to have another floor in the hall or more? Do you have space all around to expand?” With his 70 year old Jat physique he ran about finding out how much expansion was possible.

When he came to stand in front of a 14th century statue of four-handed Sarasvati, I asked him, “Dr. Anand, at the feet of the idol one can see a ram. How do you explain that (since her vehicle is a swan)?” He replied, “Hindu mythology has neither head nor tail. People have let their imagination run wild and conceptualised as they wished.” I said, “According to the Curator, to take humanity from animal level to the human is the sadhana of knowledge and from there to a super-being. So at the feet of the idol the ram symbolises animality. What do you think?” He promptly exclaimed, “Puranic stories are all hotch-potch. They make no sense at all.”

Then he changed track: “Under the Museums head of account the central govt. has 22 lakh rupees lying. Come to Delhi. I will get out at least a lakh and a half for this museum of yours. If you can’t manage the wherewithal for the Delhi trip I will give you that too.” Suddenly he said, “You have many statues of the same type. What is the need of keeping the same type of image of the same century? Exchange them for cash. You will get lakhs of rupees and with that make this museum attractive.” The museum had several images of barefooted Surya which was a rarity since post-Kushan times Surya is always booted.

He was going on talking non-stop. “Instead of that as your town is filthy so is its peculiar godown-like museum. Can’t you make a garden in the open area of the compound? Fixing firm netting along the boundary wall it can be turned into an enchanting garden. That will prevent Naxal attacks and stealing of flowers.”

At the dining table in the circuit house five of us were seated: Dr. Anand, Miss Sahiyar, Ajit Neogi, Sudhir Chakraborty and myself. Dr. Anand was bare-bodied now, talking incessantly. Some words were unintelligible because of his peculiar accent. Discussing politics he said in a grave voice, “Look, Mrs. Gandhi is very honest and sincere. I have taught her in our socialistic school. But she hasn’t learnt even the A,B,C of socialism. She will be ruined by that Y.B.Chavan (Finance Minister) and teams of innumerable corrupt followers. She has only 5 or 6 sincere and honest followers. They are lying hidden. And that Dange, chairman of the CPI! Is he a communist at all? He is worse than a bourgeois. But he understands politics and knows the tricks. I have respect for Prof. Hiren Mukherjee, a true gentleman, honest, noble communist. However, whatever you might say, CPI is practising “tail-ism” (tail behind the most progressive elements of the working-class movement, by reflecting in their politics only the most reactionary views of the masses). CPI(M) had also tried to do that but they don’t get any gate. None of them are communists. For them communism is a step to climb to power. The true communists are the Naxals, but adventurist ideas have spoilt them. If I were younger, I would have been their leader. And Chyavan? The other day he made away with about a crore of rupees. Look, Mrs. Indira will not be able to establish fascism in India. Democratic socialism is a nonsense. Disguised as democracy, dictatorship will prevail whose central point is Indira. But the form of that dictatorship will be Indian. Europeans like to finish-off the opposition but the nature of Indians is much softer. Indira has that nature. But whatever you might say, Indra is playing marvellously. She is batting with a firm hand. Morarji, Sanjeev Reddy, your Atulya Ghosh are overturned. They will not be able to rise up again. Bureaucracy will be ended. Only the central point of power will remain: Indira.”

Emergency had not yet been declared.