Yudhishthira’s Questions and Bhishma’s Answers

Suganthy Krishnamachari

The Book Review, Feb. 2024

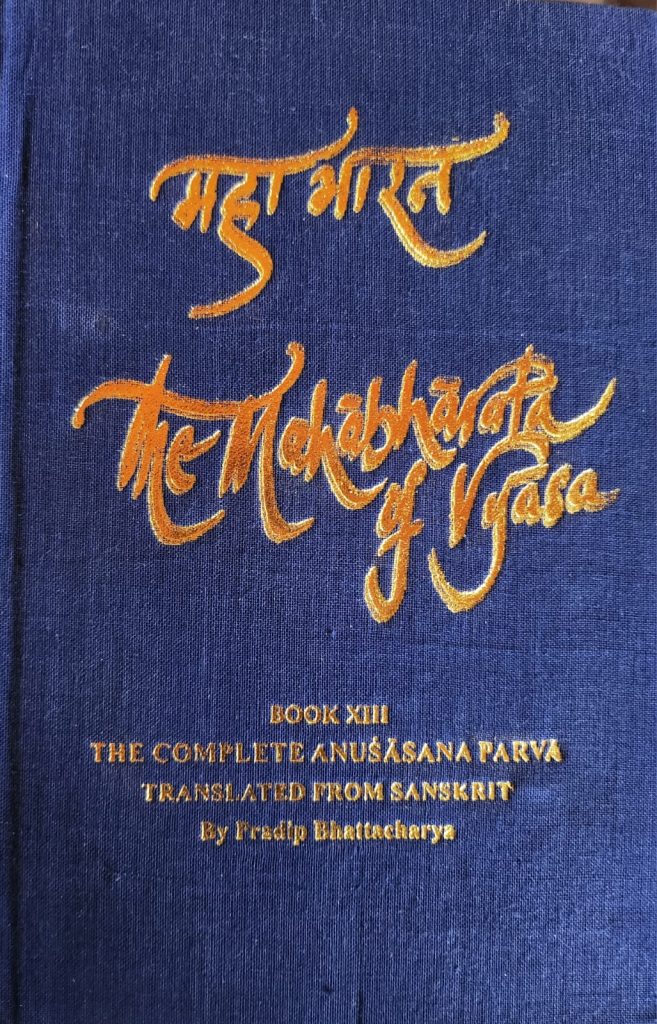

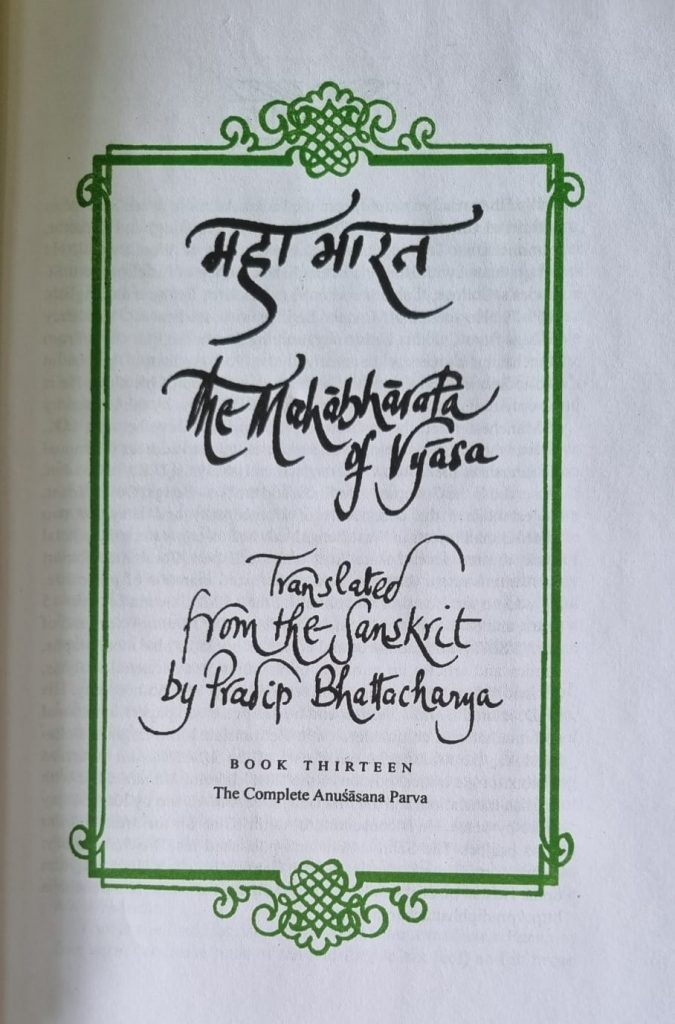

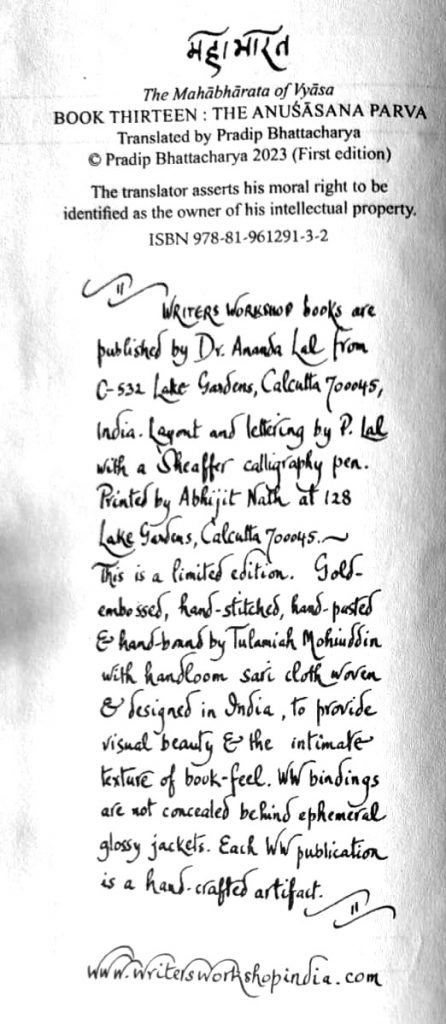

THE MAHABHARATA OF VYASA: THE ANUSĀSANA PARVA | (VOLUME 13) By Veda Vyasa.

Translated from the original Sanskrit by Pradip Bhattacharya. Writers Workshop, 2023, pp. 1256, Rs. 3000.00

The Mahabharata of Vyasa: The Anusāsana Parva, translated by Pradip Bhattacharya deals with Yudhishthira’s questions to Bhishma and the latter’s answers. It also has Uma’s questions to Shiva and his answers to her.

Bhishma is not perfect, is a flawed character himself. When Chitrangada, son of Shantanu by Satyavati died, his brother Vichitravirya ascends the throne. Bhishma does not want the family line to end. He could well have approached a royal family for a bride for the young king. But instead, he abducts three princesses as brides for his brother. It is ironic, therefore, that in the Anusāsana Parva, he tells Yudhishthira that swayamvara is an excellent form of marriage for Kshatriyas, and condemns marriage following abduction (rakshasa type of marriage) as adharma. And yet, he stopped the swayamvara of the three princesses and abducted them. In the Anusāsana Parva, he talks of the respect that we must show to wife, mother, elder sister and so on. How then does one explain his inaction when Draupadi was being disrobed? The Anusāsana Parva shows us what a bundle of contradictions Bhishma was.

These are among the many verses Bhattacharya quotes, before translating them. The reader will find this highlighting of important shlokas in Bhishma’s discourse useful. It makes the book a ready reckoner for those looking for specific topics in the Anusāsana Parva.

In Section 122, Verse 28, Bhishma says that if someone grants freedom from fear to all beings, then he is granted freedom from fear of all beings. Here Bhattacharya quotes the verse:

abhayam sarvabhutebhyo yo dadati dayapara

abhayam tasya bhutani dadatity anushushruma.

It was Bhattacharya’s reproduction of the original verse that caught this reviewer’s eye and helped make the connection to Vibhishana Saranagati. In Valmiki Ramayana, when Vibhishana arrives at Rama’s camp, Rama says:

sakrd eva prapannaya tavasmi iti ca yacate

abhayam sarva bhutebhyo dadami etad vratam mama

If a person surrenders to Rama just once, then he will ensure protection from all beings for that person, promises Rama. This Ramayana verse is often quoted in Visishtadvaita as proof of the efficacy of surrender. The idea is expanded

in the Anusāsana Parva, where all beings grant freedom from fear to a practitioner of ahimsa. The verbatim quoting of verses, even while providing translations, makes Bhattacharya’s book useful for researchers, looking for cross-references.

Bhishma has some practical advice for Yudhishthira about the need to care for tanks, which present-day rulers and administrators would do well to read, for in the modern world water bodies are being increasingly lost to urbanization.

Apart from Bhishma’s talk on dharmic practices, there is also some science in the Anusāsana Parva. In Section 110, verse 17, Bhishma warns against seeing the rising or setting sun or the midday sun directly. Never look at the sun in an eclipse or its reflection in water, he warns. Science tells us that looking at the sun directly harms the eyes. And even during an eclipse, one has to view the sun only through eclipse glasses or a telescope fitted with a special purpose solar filter. Seeing the sun’s reflection in water or snow can cause photokeratitis, when reflective UV rays result in

blindness.

Anusāsana Parva gives some interesting names of Vishnu, which one does not find in the Vishnu Sahasranamam. Here are a few: Yugantakaraa: Yuga-ender; Shiva pujya: adored by Shiva; Bhutabhavya bhavesha: past, present and future; Samkrta: piercer; Sambhava: source; Brihaduktha: loudly lauded; Jvaradipathi: lord of fever. The Anusāsana Parva also gives 1008 names of Shiva.

In Section 119 Bhishma lays down what we know as the golden rule: do unto others as you would want them to do unto you.

Bhattacharya’s translation is in verse form, and therein lies its appeal. As GK Chesterton said, ‘… The soul never speaks until it speaks in poetry…In our daily conversation, we do not speak; we only talk.’ Reading Bhattacharya’s translation is like listening to Vyasa speak to you through English verses, with Sanskrit verses interwoven into his narrative.

Bhattacharya often gives a Sanskrit name or epithet and then gives its meaning in English alongside. But the

flow of the translation is never impeded because of this bilingual presentation. This kind of presentation, in fact,

gives us an idea of the richness of Sanskrit. While agni means fire, it isn’t the only Sanskrit word for fire. And it helps when Bhattacharya writes—pavaka: bright agni; chitrabhanu: variedly radiant agni; vibhavasu: resplendent agni; hutashana: oblation eater agni. Had he just used fire instead, the translation would have been bland. In some cases, he retains original Sanskrit words like maha, for example, which finds a place in the Oxford dictionary. So, we have maha fortunate, maha energetic, maha souled, maha mighty (section 2, verse 9). No qualifying English adjective or modifying English adverb is used. And one must admit that ‘maha fortunate’ and ‘maha energetic’ read better than ‘very fortunate’ or ‘very energetic’. Sometimes the translator retains Sanskrit words and adds some suffixes as he does with puja, namaskar and pranam. In these cases he adds an ‘ed’ at the end of each word (example puja-ed, pranam-ed), and this sounds rather odd. And horribler than the horriblest (Section 148, Verse 49) can do with some rephrasing.

Bhattacharya’s is a monumental work, splendid and impressive, and would be a great addition to any library.

Suganthy Krishnamachari is a Chennai-based freelance journalist, and has written articles on history, temple architecture, literature, mathematics and music. Her English translation of RaKi Rangarajan’s Naan Krishnadevaraya, and Sujatha’s Nylon Kayiru were both published by Westland Publishers.