Meena Arora Nayak: Evil in the Mahabharata, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 355, Rs. 650/-

Meena Arora Nayak: Evil in the Mahabharata, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 355, Rs. 650/-

Lately one has noticed a trend among American scholars of arguing that ancient Indian texts instead of celebrating the primacy of Dharma as the foundation of a meaningful life are actually subversive. Beginning with Emily Hudson’s Disorienting Dharma in 2013, it has been followed up by Naama Shalom’s Re-ending the Mahabharata: The rejection of Dharma in the Sanskrit epic in 2017, and in 2018 by Wendy Doniger’s Against Dharma and the book under review. One is reminded of Lytton Strachey’s debunking of Eminent Victorians by highlighting their warts.

“Where there is Dharma, there is victory,” so says the Mahabharata (henceforth, MB). Nayak, professor of English in the USA and a novelist, has marshalled a long litany of accusations to prove that MB “calls all in doubt.” Her thesis is best stated in the words of Karna (which strangely she does not quote):-

“Those who know dharma

Have always proclaimed

That dharma protects those

Who cherish dharma.

I have always cherished dharma

As best as I could.

It has harmed me.

It forsakes its bhaktas.

It protects no one.” –VIII.90.88 (The P. Lal translation)

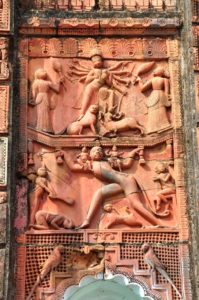

What she chooses to overlook is Krishna’s comprehensive demolition of Karna’s claim in the very next section. Of course, she sees Krishna and the semi-divine Pandavas as metaphors created by Brahmins to absolve people from accountability for immoral acts. She sees “dharmayuddha” as a dangerous paradigm for the ends justifying the means. She claims that the (MB) has been used to exploit women and “the others” by deifying characters exemplifying unrighteous conduct; that people never realise that the Gita tradition and the narrative do not tally. She begins by making much of the long discredited Aryan invasion hypothesis propounded by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1920s. She splits this into three waves: Old (pre-5th century BCE); Middle (5th century BCE to 100 CE) and New (post 1st century CE). To this she adds a euhemeristic interpretation of the Devas being these Aryans who split from the Ahura-mazda worshippers, invaded India, demonised the indigenous people and “usurped” the wealth of these Asuras, Nagas and Rakshasas, i.e. the “others”, the Nagas being targeted as devotees of Buddha (there is no such reference in the MB). The original inhabitants were the “dasyus”, later called Asuras and assigned the Shudra caste. In that process she makes some astonishing claims such as, “the atheistic, amoral Vedic system” (despite all the hymns lauding multiple deities); the epic was first “2,400 verses” (actually 24,000); eating beef was “considered reprehensible” (the MB celebrates Rantideva for his sacrifices of cattle so huge that the river running red with their bloody skins was named Charmanavati); there is little evidence of moksha-dharma (it is as large as the raja-dharma portion of the Shanti Parva); the Aryans moved “westward from the Indus Valley…(to) Kashmir” (the geography is puzzling); “myth is empirical truth”; The first Kaurava to fall is “Bhima”.

She asserts that the Vedic ethical “rita” (she has just called the Vedas amoral) was replaced by a theistic, “desire-oriented concept of purushartha” in the MB and that dharma “subverts” the cosmic rita to “a wholly earthly scheme.” By extolling sacrifices, the MB “promote(d) violence against the ‘other’…resurrected evil practices that the system had already expunged.” This in the face of constant exhortations to pursue righteous conduct, as it leads to Svarga, and non-attachment leading to moksha. She refers to M.N.Dutt (1934) while the bibliography has “P.N.Dutt”. There are Sanskrit spelling mistakes: “Shanti” with both vowels elongated instead of only the first; “daivya” where “daiva” is meant; “mahatamaya” instead of “mahatmya”, “vasva” instead of “vasava”; “asidharavrata” is not “fine-edged as an arrow” but “sharp as a swordblade”. Despite being a professor of English she uses peculiar words like “egoity”, “capsuled”, “intestine feuds”, “slayed”. What happened to the editors of OUP (India)?

Nayak takes flagrant liberties with the text, possibly presuming that the general reader will accept her assertions as facts. The snake sacrifice is “diabolic” because it is “necrophilic” (coitus with corpses of snakes?). In the Uttanka story he is said to create fire from the “horse’s nostrils” whereas smoke issues on blowing into its anus. She turns the moon and soma into the “lunar earth goddess slandered as Nirrti”, whereas it is always a male deity. In the myth of Garuda she interprets the slavery of Vinata as the time the Aryans took to replace indigenous female deities by their solar male gods, although her slavery is to her co-wife Kadru, not to any male. She has Gandhari abort herself by hitting her belly “with an iron rod” which is nowhere in the text.. Nayak invents this to link up with the iron bolt causing the destruction of the Yadavas and, more far-fetched, as “a reversal of Eliade’s sacred pole symbolism” of consecration. She misquotes the Vana Parva where Markandeya does not tell Yudhishthira in the first person that he will create a new yuga, but that Kalki will do so. There is no use of the first person singular in the passage at all. When Brihaspati rapes his sister-in-law Mamata, he does not curse her but the son in her womb to be born blind.

The logic followed is also flawed: following dharma means doing good; the idea of goodness leads to attachment (why?) i.e. ignorance and therefore to evil! Since nishkama karma has liberation as the goal, it injures those in relationships, which is adharma! She ought to have paid attention to the story of how Shuka attains moksha. She asserts that by linking detached action with accomplishing wealth and pleasure “an ethical trap” was created. A person was encouraged to enjoy worldly life while karmic life condemned it. The only solution is to cease to act, or to follow desireless action, both being impossible.

Nayak makes an excellent point that while the ethics envisage pursuit of four-fold “purushartha” (dharma, artha, kama, moksha), morality is left to the individual and is situational. It is more “apad-dharma” being practised—when anything is justifiable for saving one’s life and property—than a Hegelian adherence to a superordinate goodness. However, her definition of morality as “what is done” as opposed to ethics which is “what ought to be done” is questionable. Further, she holds, the MB hardly follows the tenets of the Gita, which, along with the didactic Shanti and Anushasana Parvas, were interpolations. The concept of Karma she finds realized not in the Pandavas but in the Kauravas, and that the former are held accountable, condemned to suffer after the war while Duryodhana goes to Svarga. The Pandavas are morally depraved, killing cousins “for wealth on sanctimonious grounds”. So Duryodhana’s attempts to murder them and cheat them of their inheritance are above board. Nayak finds that the MB has deepened the differences between traditional beliefs leading to creation of “morally corrupt customary laws” and “societal inequities”. Further, with no evidence she asserts that the Shaivic elements (Shiva’s presence is quite significant) are “all later interpolations”. Arjuna’s acts in Khandava forest are heinous, being purposeless violence, while Ashvatthama’s nocturnal massacre of sleepers is avenging his father and fighting for victory. In his condemnation Nayak sees Vaishnava condemnation of Shaivism, and the epic’s bias justifying violence by Krishna and his followers as necessary. To her, Shishupala is another Shaiva and Shiva’s collaboration with Krishna and Arjuna is an interpolation, for which no evidence is advanced. Arjuna’s release of the Brahmashiras to counter Ashvatthama’s makes him culpable as “it reeks of abuse of power” reflecting “how Vaishnavas behaved whenever they gained advantage.”

Nayak even misreads the epic as when claiming that Bhishma refuses to let Karna fight being jealous that he may turn out to be the greater warrior. The reason is very clearly stated by Bhishma from his bed of arrows to Karna. Karna, she claims, was only paying Draupadi back for humiliating him although he brought down the mark in her svayamvara. Actually, he never shot the arrows, nor does Draupadi ever insult Duryodhana as “the blind son of a blind father”. Krishna’s violence in response to Shishupala’s abuses “is shocking; no mythical justification…excuses it.” Duryodhana, she finds, has no free will to change his karma and, therefore, no matter what he does he is condemned as evil! That flies in the face of his deliberate machinations from adolescence to destroy his cousins. For Nayak, despite his adharmas, he is distinguished by “secularity” and “purusharthic dharma” in pursuing dharma, wealth and pleasure. But where is his pursuit of dharma and secularism seen? Duryodhana, she asserts, is portrayed as “a warrior supreme” but never Arjuna. Duryodhana is “aghast” at Yudhishthira staking Draupadi. Bhasa portrays the true nobility of Duryodhana not the Brahmin-redacted MB. Is all this not special pleading? Finally, “Krishna not only makes the victory of dharma imperfect, he also makes the dharmakshetra an adharmakshetra.” In teaching society how to act the MB tradition fails because its “exemplars of dharma…are deeply deficient dharma heroes.”

As dharma is ambiguous the characters are guided not by universal ideals but by their relationships. Universal good being fought for would be dharmayuddha—but that is not so. In this, Nayak overlooks the very reason for the war having been structured to relieve the earth sinking under the burden of oppressive rulers. She argues it is a war against a previous form of dharma by the new Vaishnavism. She asserts that by epic times animal sacrifice was seen as adharmic vide ahimsa paramo dharma. The repeated emphasis placed on this implies the existence of widespread violence and leads to sanction of himsa as “good violence”! Violence being approved in emergencies, the idea of goodness was in flux then as now. She posits a clash between the ethics of Kshatriya conduct justifying lying and morality whereby such action is immoral and lands one in Naraka. Arjuna fails to resolve his moral dilemma: he will not kill Drona, hesitates to kill Bhishma and grieves for Abhimanyu, failing to sunder his relationships of self. He does gain freedom from doubt and the victory of unequivocal dharma. Unquestioning practice of inherited traditions like varnashrama led to varna-based dharmayuddhas against peoples beyond the vedic fold named by Bhishma and Karna. Nayak confuses race with caste in asserting that the concept of ‘the other’ was based on people’s birth, whereas it is clearly those following non-Vedic practices. She even says, “Hitler’s words almost mirror Arjuna’s warning about deterioration of Aryanism” from miscegenation (p. 292) and equates Nazis with twice-born Hindus perpetrating violence upon lower castes. Sectarian violence based upon religion is another facet of Nayak’s dharmayuddha e.g. Vaishnavism vs. Shavism and Shramanic traditions.

Nayak finds that the MB proves that claim to ownership can cause dharmayuddha (cf. Kunti’s advice to her sons via Krishna). The question of who is the legitimate ruler of Hastinapura remains unresolved, hence the Pandava claim to dharmayuddha is negated. Further, for the Pandavas the end justifies the means: “just the fact that the Pandavas destroy the peace and happiness of an entire land proves that their yuddha is an adharmayuddha.” (p. 309). Bhishma’s advice to Yudhishthira never to forgive an enemy plunges people into a cycle of endless wars, almost wiping out a race or community: “The whole MB war is a series of so many blood feuds that it reduces the ideology of a dharma war to gratuitous war-mongering.” The code of conduct in war laid down by Bhishma is constantly violated. Nayak quotes Cicero in “Pro Milone”: silent enim lēgēs inter arma— silent is law during war. What Kautilya recommends is what both Kauravas and Pandavas practise. Nayak’s presentation of this is very interesting, specially breaking the enemy by ruining his reputation (constantly condemning Duryodhana as wicked) and spreading rumours about one’s own power e.g. Pandavas being born of gods, Krishna’s divinity.

Finally, Nayak points out that the MB is an allegory of the yuddha of the self, destroying the baser impulses for self-realization. It is the only MB tradition that succeeds. Opponents disguise themselves as goodness, hence the need of deceit to destroy them. Preserve the Higher Self by destroying the baser self. The violence is figurative. War is a metaphor acting “as a catalytic goad to elicit deep questioning about moral and immoral behaviour.” In that case, is it a parallel “Pilgrim’s Progress”? Duryodana is evil because he knows only his social self, has no internal life. Only after winning the internal war should the external war be undertaken, otherwise it will have an evil causality injurious to self and others. The victories will be those of the lower self. Conflict with desire is yuddha.

The greatest tragedy, according to Nayak, is that when clear guidance is needed the MB tradition supplies ambiguities leading to confusion but no clear answers. However, its internal war is relevant today to lead everyman to victory over the lower self. Actually it convolutes the path. Thus, “the dharmayuddha of the Mahabhrata fails in its practicability…The only tradition the Mahabharata actually institutes is one that makes enquiry customary.” As Dharma is subtle, only the consequence of conduct reveals whether it is right or wrong and this is often different from the expectations of the agents. Not only are their intentions unrealized but the ideologies are also not uniform or absolute. Incomplete executions of good and evil action create paradoxes. The MB provides not answers but ways of contextualizing enquiry according to place, time and circumstance.

Nayak plots the evolving thought through the example of Vritra, an evil power withholding waters in the Rig Veda, but in the MB a Brahmin whose murder is condemned. Nahusha asks gods why they did not stop Indra from cruel and vicious deeds. He even says Vedic hymns are not authentic. Nothing was sacrosanct during the melting pot situation when social changes were occurring. There was conflict between old Vedic dharma and the new Krishna-ized dharma. The Purusharthic goals of artha and kama are misused for selfish gain because dharma’s parameters were flexible. Misogyny is disguised as wisdom when Bhishma denounces women as sunk in tamas who stupefy men, objectifying them as to be blamed for men’s immorality.

The MB calls itself “collyrium” which is the wisdom of questioning what is right and wrong, eradicating the ignorance of narrow-mindedness. It created a tradition of fluid enquiry to question evils in every era. Its becoming a Shastra stopped its evolution. Nayak argues the necessity “to re-examine the text as a chronicle of its time…not binding traditions but metaphors of enquiry into the changeable human condition.”