APPROACHING ADI-KAVI VALMIKI[i]

Pradip Bhattacharya

The Department of Comparative Literature of Jadavpur University founded by the litterateur Buddhadeb Bose in 1956 was the first such in India. It has now embarked upon an ambitious project: a series of research publications in four categories, viz. Texts, Contexts, Methods; Indian and Asian Contexts; Literature and Other Knowledge Systems; and Lecture Series. The overpriced slim volume under review belongs to the last category. From the editors’ Introduction it seems that Goldman did not deliver this lecture but sent it as a written contribution. This is a pity, because documented interaction with an audience would have made it a far more significant publication. This extremely well-written “lecture” is not much more than an introduction for beginners, albeit a very competent one, to Valmiki’s work and hardly falls under the rubric of “research”.

The Ramayana (R) presents specific hurdles before the modern reader: it depicts a civilization of circa the first millennium BCE far removed from us; its language is ancient Sanskrit, which is not easily accessible. Further, Sanskrit did not have a principal script universally used. The R has spawned widely varying versions in almost all languages and different scripts of South and Southeast Asia “from Afghanistan to Bali” and is depicted in varied media. Surprisingly, Goldman makes no reference to the Belgian priest Camille Bulcke’s encyclopaedic Hindi study of these variations.[ii]

Adopting the linguist Kenneth Pike’s terms emic (subjective) and etic (objective), Goldman identifies two types of group-approaches to the R. In the former, fall variations in Indian languages and media. The latter is consists of scholarly studies in various disciplines world-wide, including translations in non-Indian languages.

Goldman asserts that the presumption of a single divinely inspired composer disseminating his composition through twin rhapsodes who recited it in toto before the public is a myth. The text would have undergone changes on the lips of differing bards and redacteurs owing to lapses in memory and improvisations responding to the changing audience and place. We can witness this phenomenon today in the “Pandavani” folk retellings of the Mahabharata (M) in Central India. Those Ramayana rhapsodes were given the collective name, “Valmiki”. Thus, like many Western Mahabharata scholars who dismiss Vyasa as a myth, Goldman denies the existence of Valmiki.

Further, he denies the possibility of so bulky a work being transmitted orally from Afghanistan to Bali without being reduced to writing, as evinced by innumerable manuscripts in circulation through South and Southeast Asia from about the end of the first millennium CE. Errors and changes occurred while copying a manuscript into different scripts. Thus, between the Northern and the Southern Indian script recensions only about one third are identical. Moreover, within each recension there are regional variations depending on the script in which the copies have been made.

A very important clarification Goldman provides is that the Baroda critical edition of “India’s National Epic” does not represent the original, but seeks to present an archetype constructed out of the best manuscripts that would be nearest to the period of the oldest available manuscripts. The abundance of textual variants poses a major problem in trying to assess the poem’s original form. Goldman hazards a guess that the R was produced around 500-100 BCE, while its oldest manuscripts go back only to the 12th or 13th centuries CE. So we have over 1700 years of no written record of the R. Therefore, “the etic reconstruction of the Ramayana’s genetic history is naturally going to be at odds with its emic receptive history of the work.” While to scholars it is a bardic poem orally performed and transmitted, to its audience it is the work of a single composer, the first poet (adi–kavi), who was a contemporary of Rama in mythical times. An avatar of Vishnu, he descended on earth to destroy demonic oppressors of sages and establish a golden age lasting millennia. Thus, according to the emic view, “it is a chapter of divine history rendered in a new form, that of poetry.” Raising the stimulating question, is the R “a poetic history or a historical poem”, Goldman leaves it hanging in the air. It would have been very interesting to study the reactions of the audience, had this been a live lecture.

Looking into the nature of the R vis-à-vis the M, Goldman notes that the former is far more poetic and emotional than the latter. The predominant emotion of the R is “karuna rasa”, pathos, whereas for the M a new emotion was added by the critic Anandavardhana (c. 9th century CE), “shanta rasa”, worldly-detachment or serenity. Earlier, the poet Bhavabhuti (c. 8th century CE), had asserted that “karuna” is the only rasa. However, in his last work Alf Hiltebeitel has argued very persuasively that the M’s rasa is “adbhuta-wonder”. Where the R holds up a mirror for rulers and families, the M portrays the incredibly complex ramifications of dharma in society and the individual.

Besides ignoring the story of Rama recounted in the M, Goldman has not noticed another structural similarity between the two mahakavyas that young Ramayana aficionado Saikat Mandal has pointed out. The Tilaka commentary on R by Nagoji Bhatta or Ramavarma (1730-1810) glosses the Uttarakanda as the “khila” (supplement) of the R just as the Harivamsha is of the M. The significance of this needs exploration.

Goldman expatiates at length on how the R records the inception of Valmiki’s composition, which is “a later addition to the fully developed work” for establishing it as the divinely inspired first poem. Its list of seven of the eight “rasas” shows it to be later than Bharata’s treatise, Natyashastra. Goldman goes on to show how the R differs from the Homeric epics in characteristics such as rapidity, being plain and direct in syntax, language and thought. He finds Valmiki hyperbolic, using rhetorical figuration aplenty, highly formulaic and repetitive, unlike Homer’s directness. The literary quality of the R is complicated, being a poem to delight while also being a chronicle. Goldman could have noted how, in all these features, the R is similar to the M and also different, as discussed at length by Sri Aurobindo in “Vyasa and Valmiki”.

Further, the R has grammatical forms that violate Panini’s rules and could be seen as poetic flaws. Its first and seventh books are of a later date, in less refined language. Goldman quotes at length from Homer and Valmiki to exemplify his arguments and to show how adept the latter is in portraying beauty in persons and in nature, including the frightful. Pursuing Abhinavagupta’s view of rasadhvani, Goldman analyses how the raw emotion of grief is sublimated by Valmiki to make karuna rasa the major aesthetic flavour of poetic composition, transmuting shoka (grief) to shloka (verse). The climax is reached in ending with Sita’s descent into the depths of the earth, leaving Rama desolate.

[i] Robert P. Goldman: Reading with the Rsi—a cross-cultural and comparative literary approach to Valmiki’s Ramayana. Orient BlackSwan, Hyderabad, 2023, pp. xvii+54, Rs.385/-

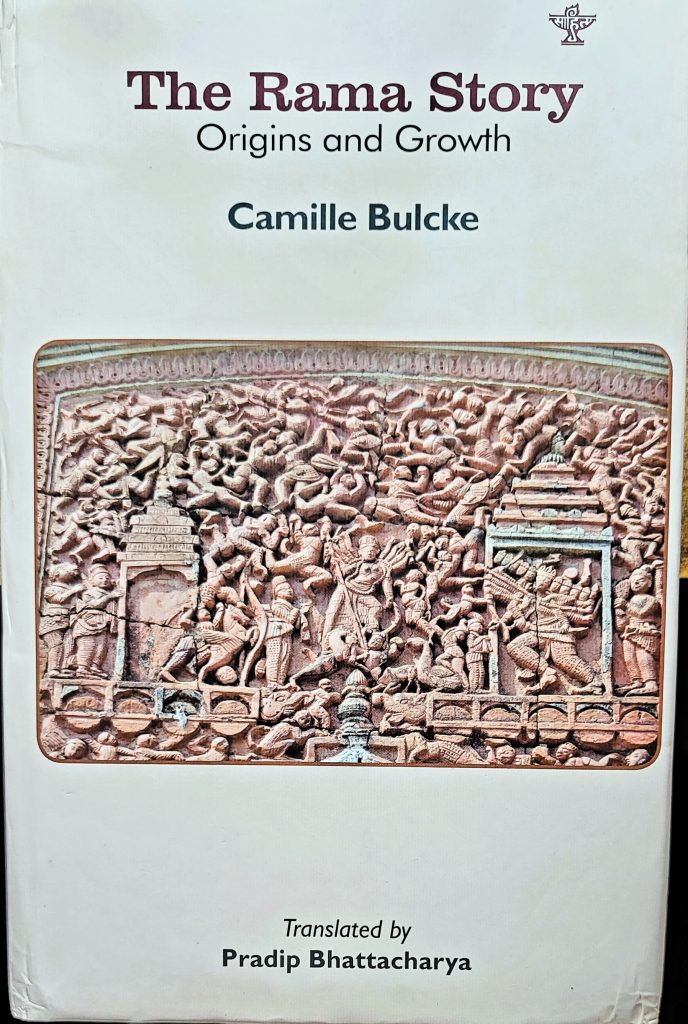

[ii] English translation The Rama Story by Pradip Bhattacharya published in 2022 by the Sahitya Akademi.