Other than the sons of Bhima, Arjuna and the Draupadeyas Vyasa does not mention names of Pandava progeny. In Jaimini’s Ashvamedha parva a new character is introduced: Bhima’s grandson Meghavarna, the son of Ghatotkacha. But there is yet another son of Ghatotkacha whose story is told in the Skanda Purana, Kumarika Khanda, chapters 59-66 by Suta Ugrashrava to Shaunaka and other sages performing a great sacrificial ritual in the forest of Naimisha. Suta narrates what he had heard from Dvaipayana (island-born) Vyasa.

Other than the sons of Bhima, Arjuna and the Draupadeyas Vyasa does not mention names of Pandava progeny. In Jaimini’s Ashvamedha parva a new character is introduced: Bhima’s grandson Meghavarna, the son of Ghatotkacha. But there is yet another son of Ghatotkacha whose story is told in the Skanda Purana, Kumarika Khanda, chapters 59-66 by Suta Ugrashrava to Shaunaka and other sages performing a great sacrificial ritual in the forest of Naimisha. Suta narrates what he had heard from Dvaipayana (island-born) Vyasa.

When the Pandavas were dwelling in Indraprastha under Vasudeva’s protection, one day Ghatotkacha arrived in the court and was welcomed with warm embraces and blessings. He informed them that since the death of his wicked maternal uncle Hidimb he was ruling the kingdom righteously and that his mother was engaged in austerities. At her urging, he had left the foothills and come to offer his respects, requesting them to engage him in some noble cause. Yudhishthira was delighted and praised Hidimba for rejecting the splendour of her husband’s royal palace for ascesis and having overcome all desire.

Turning to Krishna, Yudhishthira expressed his anxiety over finding a proper bride for Ghatotkacha. Krishna thought a little and stated that the proper spouse was waiting for him in the city of Praagjyotisha. She was the daughter of the Daitya Mura of amazing feats, intimate friend of the Daitya Naraka, both of whom Krishna had slain. After Mura fell, his valiant daughter Kamakatankata attacked Krishna and, cutting through his shower of arrows, struck Garuda’s head with her sword, felling him unconscious. When Krishna lifted the discus to slay her, the goddess Kamakhya appeared and announced that she had granted Mura’s daughter the boon of invincibility in battle and gifted her the sword, shield, spear and incomparable intelligence. Therefore, honouring her boon, Krishna ought not to fight the daanavi. The goddess made peace between Kamakatankata and Krishna. She directed the Daitya amazon that as she was to become the daughter-in-law of Krishna’s cousin Bhima, she ought to touch her future father-in-law’s feet. Krishna blessed her and asked her to continue living there, looked after honourably by Naraka’s son Bhagadatta.

Kamakatankata vowed to wed only that man who could baffle her with a riddle and defeat her in a duel. Everyone who attempted lost his life. Yudhishthira refused to permit their grandson to undertake such an enterprise, howsoever wonderful the prospective bride’s talents might be and preferred to search elsewhere. Bhima, however, insisted that the valiant must attempt the impossible, otherwise how would fame be theirs? He advised that his son proceed alone immediately to win Mura’s daughter. Arjuna supported him, pointing out that success had already been foretold by the goddess Kamakhya. Krishna approved but asked Ghatotkacha what was his own wish. He responded, “I do not boast, but I wish to assure my elders that you will not have to be ashamed of me.” With their blessings, he left. As he left Krishna told him, “When you speak to her, think of me. I will ensure your victory by making your intelligence and your prowess invincible.”

Ghatotkacha reached the outskirts of Praagjyotisha city and approached the gates of a huge palace with a thousand golden spires. From within it arose the music of flutes and veenas and thousands of maidservants could be seen scurrying about. Bhagadatta’s retainers were rushing back and forth enquiring, “What is the sister’s wish?” Approaching a maid named Karnapravarna he spoke softly to her, “Lady, where is Mura’s daughter? I come from afar to meet her.” “Mighty-armed one,” she responded, “Why do you seek the daughter of Mura? Crores of lusting men like you have met with death at her hands. Your appearance I find most amusing, like a pot and all the hair sticking up. Valiant one, I touch your feet and am at your disposal. Lusty one, stay here with me and enjoy yourself. I shall provide you three attendants with wives.” Ghatotkacha replied, “Auspicious lady, you have only proved what I have heard about all of you. But my heart does not accept your words. Once desire fastens upon a goal it is not diverted elsewhere—so what can I do? Today I shall either defeat your mistress and sport with her or, being defeated, follow the path of the other suitors. Hence, O Karnapravarna, swiftly carry my words to your mistress. May she grant audience immediately and welcome the guest.”

The night-foraging maiden ran at once to where Kamakatankata sat within the palace and said, “Devi, a youth of appearance unique in the three worlds is at your door wishing to meet you. Command what is to be done.” Kamakatankata said, “Let him come in at once! Why the delay? Perhaps finally, after so long, through divine intervention my time has come.” Hearing this, Karnapravarna returned to Ghatotkacha and said, “Lust-crazed one, without delay rush to that death-incarnate.”

Thereupon Bhima’s son entered the city like a lion striding into a mountain cave. He saw Kamakatankata reclining on a swing surrounded by doves, parrots and beautiful maids. In beauty and youth she seemed like the goddess of love Rati. Decked in ornaments, she flashed like lightning. Ghatotkacha thought, “Uncle Krishna has truly chosen the right partner for me. So what if previous suitors have been destroyed? The body, after all, is subject to decay. If the bodies of lusting men get destroyed because of such women, let it be so.” He said, “Adamantine-hearted one, I come to you as a guest. Therefore, greet me appropriately.” Kamakatankata was surprised to hear this and noticing Ghatotkacha’s appearance cursed herself, “Alas! If I had not sworn such a vow already, he would certainly have been my husband.” She said, “Sir, you have come in vain. Depart with your life. And should you desire me, put forward some proposition immediately. If you can throw me in doubt, I shall be yours to command. Otherwise you shall die at my hands.”

Ghatotkacha called on Krishna, lord of all, and began to tell a story.

“The wife of a man who had no control over his senses died after giving birth to a daughter. When she bloomed into a woman, that lustful man was crazed with desire and one day embracing her said, ‘Dearest, you are the daughter of one of my neighbours. I have looked after you so long to make you my wife. Therefore, now fulfil my desire.’ The daughter thought it was the truth and accepted him as her husband. Thereafter, she gave birth to a daughter. Now tell me, is that girl that lustful man’s granddaughter or daughter? Answer me if you can.”

Kamakatankata thought over the riddle for a long time but could not arrive at an answer. Then she rang the golden shackles of the swing and immediately crores of Rakshasas, lions, tigers, boars, buffalos and leopards appeared and rushed to devour Ghatotkacha. Seeing this, he laughed and from his nails produced double the number who ate up those Rakshasas and others in an instant.

Then Kamakatankata sprang up from her swing to take up her sword. Bhima’s son at once seized her hair with his left hand and threw her on the ground. Pressing his foot on her throat he threatened to slice off her nose with the knife in his right hand. Mura’s daughter was unable to move and said, “Lord, in riddle, prowess and physical strength—in all three you have defeated me. I salute you as your servant. Free me and command me what you will, I shall obey.” Ghatotkacha said, “If that be so, then you are free. You are welcome to try again.” Kamakatankata replied, “O mighty warrior, I know who you are. You are the first among the powerful, lord of all night-roamers, the lord of guhyakas Kalanaabha and have taken birth on earth to protect the Yakshas. Goddess Kamakhya has revealed this to me. I surrender myself, my attendants, this palace, everything to you. O Lord of my life, command me, what I should do.” Ghatotkacha said, “Daughter of Mura, one whose parents are alive ought not to marry in secret. Therefore, take me now to Indraprastha. It is our custom that the bride carries the groom. There, with my elders’ permission, I shall marry you.”

Mura’s daughter then informed her guardian Bhagadatta of everything and with a host of gifts from him carried Ghatotkacha on her back to Indraprastha where they were married to the great delight of Kunti and Draupadi. The Pandavas were glad to receive all the wealth. Thereafter the couple returned to Hidimba forest where the Rakshasas held great celebrations to the clash of cymbals. In due course a son was born who achieved youth immediately after birth, as Rakshasas do. Dark of complexion like blue clouds, his face was like a pot, eyes large, hair all standing up. Touching his parents’ feet he requested them to name him and advise him about what he ought to do. Embracing him Ghatotkacha said, “Son, since your hair is curled, I name you Barbareek. About your future course of action, I shall enquire of Vasudeva after reaching Dvaraka.”

Leaving his wife there, Ghatotkacha took to the skies with his son and reached Dvaraka where the guards raised an uproar warning everyone about the arrival of two Rakshasas. Ghatotkacha announced their identity and requested audience with Krishna who immediately had them admitted into the court. Barbareek then enquired of Krishna how to achieve excellence in keeping with his birth. Krishna said, “Maurveya, you are born in a Kshatriya family, hence acquire immense prowess whereby you may punish the wicked and protect the virtuous. Thereby you shall win heaven. It is by the grace of goddesses that illimitable strength can be obtained. Hence, go the secret spot located at Mahisagara on the seashore where sage Narada has brought together all the goddesses. Worship the four goddesses of the directions and the nine Durgas. Finding them all in one place is a unique opportunity. If they are pleased, there is nothing—power, wealth, fame, sons, wife, heaven, even liberation—that you cannot obtain.” Turning to Ghatotkacha, Krishna said, “Your son is extremely righteous, therefore I name him ‘Suhridaya’, the good-hearted one.”

Ghatotkacha returned to his forest, while his son departed for the secret teertha Guptakshetra. For three years he lived in the place named Dagdhasthali, worshiping the goddesses who appeared before him and blessed him with incomparable prowess. They advised him to wait there for some more time to meet Vijaya, which would be to his advantage. A Brahmin of Magadha named Vijaya arrived there after some time having learned in Kaashi a special kind of worship by which for a long time he had worshipped the seven lingas and the goddesses to gain knowledge. In a dream the goddesses told him to continue the ritual with the help of Barbareek. On the fourteenth night of the dark fortnight Vijaya and Barbareek, having fasted, created a devi-mandala in front of the Siddhaambikaa temple, fixing a mantra-sanctified sword in its midst and eight wooden posts bound with thread around the mandala. Vijaya asked Barbareek to keep awake praying to Devi and to guard him from all harm. He proceeded first to pray to Ganesha, then the Kshetrapalas, then the Yakshi Sunanda who was in the form of a banyan tree on the shore, and began to repeat the Aparajita Mantra from “Om namo bhagavate” till “namohastu te svaha”.

In the first hour of the night a woman manifested there, clad in a single bloody cloth, hair flying wildly, terrifying eyes, gleaming white teeth—an image that would terrify terror itself. She was weeping loudly. Vijaya was frightened but Barbareek went up to her and embracing her neck began to weep even more loudly. Surprised, that woman tried to smite him with a sword, but Barbareek seized her by the throat and immobilised her. After roaring in pain for some time, she begged to be released and, when he let go, fell at his feet. “I am the shape-shifting rakshasi Mahaajihvaa and live in the cremation grounds of Kaashi. If you spare me, I shall engage in austerities that will benefit all creatures. If I do not do so, may I be reduced to ashes.” Barbareek then let her go and continued to stand guard.

At midnight a terrible roaring was heard and a huge hill became visible from which trees and rocks began to rain along with hail and blood. Not at all fearful, Barbareek took up a hill twice that size and jumped upon that hill so hard that it shattered to pieces. Repalendra then assumed a hundred-headed form, spitting fire from its many mouths. Barbareek did the like and attacked it with bow and arrows, then with sword and, when both got broken, they fought with fists. Finally, Barbareek suddenly lifted up the demon and spinning him round, flung him on the ground, killing him and threw his body afar. The place where he fell became a village named Repalendra. This terror of sadhus was the lord of the cremation ground of Avanti.

After the next hour again from the west a thunderous sound was heard and the earth quaked. Then, like lightning falling from the clouds, a she-mule arrived. Bhima’s grandson laughed, jumped upon that mule and tried to stop it by hitting it on its snout repeatedly. Instead it grew furious and with a mighty neigh leaped threw Barbareek on the ground. He then seized its legs and threw it on the ground. As it rose up, he again hit it so hard that its teeth fell out. He began wringing its neck and throttled it to death. Thus that demoness leader of Shaakinis met her end. The village at the place where Barbareek threw her became known as Duhadruha.

At the fourth hour a peculiar shaven headed naked mendicant wearing peacock feathers appeared, exclaiming, “Alas, non-violence is the supreme dharma. So how can fire be lit? For to light fire many tiny creatures have to be slain.” Hearing this Barbareek laughed and said, “Agni is the mouth of all gods, therefore the proper ritual is to place offerings in it. You speak falsely, therefore, wicked one, you need to be taught a lesson.” With a leap, Barbareek seized him and with a blow on his mouth that broke his teeth threw him on the ground unconscious. On regaining consciousness, he assumed a terrifying demon’s form and fled into a cave within which a city named Bahuprabhaa existed. Barbareek followed him and was attacked by many Palaashi Daityas with arms. Like a musth elephant entering a forest of reeds he trampled them all to death. Then Vasuki and other Nagas came and soothed him with sweet praise for killing the demons who used to torment them. They asked him to choose a boon. Barbareek requested that Vijaya should obtain what he was praying for. “So be it,” they said gladly.

On his way back through the tunnel Barbareek saw at the foot of a banyan tree a bejewelled linga being worshipped by many Naga maidens. Surprised he enquired of them who had established this dazzling linga and where the paths seen around it led. One of the heavy hipped, large breasted women shyly glanced at him and smilingly said that lord of the Nagas, noble Shesha had established this linga and to the east the path led to the Shri mountain on earth. The path had been made by Elapatra Naga. The path to the south led to Shurparaka teertha and was made by Karkotaka Naga. To the west the path led to the glorious pilgrimage spot of Prabhasa and was made by Airavata Naga. The path Barbareek was taking was to the north and led to the secret spot where the Siddha linga existed. That tunnel was known as Shakti cave and was made by Takshaka. Saying this the maidens all wished to know who he was and begged him to wed them and stay there. Barbareek announced his identity and refused their offer as he had opted for celibacy. Prostrating before the linga in salutation, he came out of the cave to find dawn breaking. Vijaya greeted him happily having completed the entire worship. Soon he began to rise upwards, greeted by showers of flowers by gods, music and dance by gandharvas and apsaras. Vijaya blessed Barbareek with victory, joy and immortality, advising him to take the crimson ashes from the sacred fire he had lit and to fling it against the enemy in war. It would destroy all foes and ensure his victory. Barbareek, however, refused the gift because the virtuous man performs service without selfish motives. The gods then told him that should the Kauravas obtain these ashes, it would lead to great evil for the Pandavas. Therefore, he ought to collect them. He complied and continued to live there worshipping the goddesses.

Thereafter when the Pandavas went into exile, they arrived at this spot while touring the sacred teerthas. Entering the temple of Chandikaa in the north for resting, they met Barbareek there. Neither knew one another because since his birth they had not met. Parched, Bhima was about to enter the pond when Yudhishthira cautioned him to wash his feet first outside it and then drink, otherwise he would be committing a serious fault. Bhima, unsettled with thirst, paid no heed, walked into the pond and washed himself there. Seeing this Barbareek shouted, “Sinful wretch, you washed yourself in the goddess’ pond! Daily I bathe her with this water and you have dirtied it. Even human beings will not touch such water, what of deities! Come out at once and then drink. If you are such an imbecile how are you visiting sacred teerthas?”

Bhima: “Brutal Rakshasa! Why are you abusing me? All water is for the enjoyment of all creatures. Sages have prescribed bathing in teerthas, which means cleaning the body. So why are you blaming me?”

Suhridaya: “True, bathing in teerthas is one’s duty, but its procedure is to bathe entering a flowing stream and in still waters from the outside unless its waters are not used to bathe deities. Violating this is sinful. Therefore, wicked fool, come out at once. If you are such a slave of your senses, why are you on a pilgrimage at all?”

Bhima: “Whether it be dharma or adharma I cannot step out. Never have I been able to bear hunger and thirst.”

Suhridaya: “Have you not heard king Shibi’s saying that it is better to live but for a moment doing a pure act than to live for an eon committing sins.”

Bhima: “Your cawing is deafening. Lament as much as you wish and die, but I am definitely going to quench my thirst here.”

Suhridaya: “Born in a dharma-protecting Kshatriya family I will not permit you to do evil. Either you come out now, or I will shatter your head with this stone.” Saying this, he threw a stone at Bhima’s head. Avoiding it, Bhima jumped out of the pond and engaged Barbareek.

After fighting for some time Bhima weakened and Barbareek began to throttle him, throwing him to the ground. Bhima fell unconscious and Barbareek began to drag him to the sea to throw him into it. Lord Rudra addressed Barbareek from the sky and asked him to release Bhima for he was his grandfather, whatever he might have done. Hearing this, Barbareek released Bhima and cursed himself repeatedly. Throwing himself at Bhima’s feet he begged forgiveness repeatedly, beating his head on the ground and weeping. Bhima embraced him and said, “Son, we have never met you, nor have you seen us since birth. We heard from Krishna and Ghatotkacha that you live here but our sorrows had made us oblivious of that. Do not grieve, for you are not at fault. The Kshatriya must punish all wrong-doers. I am very pleased and we and our ancestors are blessed that we have so virtuous a grandson.” Barbareek said, “No penance has been prescribed for progeny who do not respect parents. Therefore I shall drown this sinful body that has pained my grandfather in the sea.” Saying this, Barbareek gave a mighty leap and reached the sea shore. Siddhaambikaa and the fourteen goddesses then manifested there with Rudra and embracing Barbareek said, “Valiant one, what is done in ignorance is not sinful. Look, your grandfather is running this way shouting your name. If you give up your body now, so will Bhima and that will lead to your incurring great sin. And if you are bent upon dying, then listen to my words: soon your death is fated at Krishna’s hands. Wait until then. For, being killed by Vishnu brings great fortune.” Barbareek refrained from suicide but complained, “Devi, you know well that Shri Krishna always protects the Pandavas in the interest of getting his work done on earth. You too came to save this Vrikodara.” Devi said, “I shall surely protect my devotee from Krishna. To accomplish my work, Barbareek will undertake a mighty battle and be renowned throughout the world as Chandil.” Saying this, all the deities vanished. Bhima took Barbareek to the Pandavas and narrated everything. Bhima established a linga named Bhimeshvara at the spot where he had been rescued by Rudra. Worshipping it at night after fasting on the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight of Jaishtha liberates one from all sins.

After halting for seven nights there the Pandavas decided to leave. In the morning after bathing in the sacred waters and worshipping the goddesses and the seven lingas, Yudhishthira recited the hymn to the Devi composed by Krishna that must be recited before commencing a journey: “O dear sister of Krishna, Mahashakti Devi, I take refuge in you with body, mind, heart and spirit. You have gifted Sankarshana freedom from fear. You dazzle like Krishna. O Mahadevi Ekanamsha , Shivey, nurture me as your son. You are formless, it is you who create this world. Knowing this I take shelter with you. Auspicious One, rescue me. Before starting all work I with my followers surrender our souls in you. Knowing this, shower your grace on me.”

As Yudhishthira said all this with folded hands Bhima, irritated, said, “O king, I see that people are wrong in pointing you out as ‘Yudhishthira the all-knowing’. For, you know nothing at all. Despite being the first among the wise and expert in all branches of knowledge will a person ever take shelter with a foolish female? You know very well, and it is so stated in all scriptures, that Prakriti who shrouds the world in illusion is inanimate and stupid. The wise call Prakriti ignorant and Purusha conscious. Prakriti is Purusha’s wife. Vain is your learning, Partha, for despite being yourself a purusha you are bowing down to that Prakriti. It makes me laugh. Sandals are not fit to cover the head. Rather, the foolish person who worships a goddess is like the man who places sandals on his head. If you needs must endlessly chant paeans like bards, then why not do so in honour of triple-city destroyer Mahadeva? Or, if you cannot praise him as he cannot be seen, why not chant a paean to the perfect purusha Dasharha Krishna by whose grace we have obtained Draupadi, you have ruled in Indraprastha and conducted the Rajasuya, Arjuna has obtained the Gandiva bow, I have slain Jarasandha and even now we wish to recover our lost kingdom from the Kauravas? Instead of that Krishna a god-like one like you is singing another’s praises! How terrible! And if you feel that being born in the superior Kuru dynasty you cannot chant the praises of the lower in status Yadava, then why don’t you praise Arjuna who has pierced the target in Draupadi’s svayamvara, defeated heroes like Karna, burnt Khandava forest, defeated kings for the Rajasuya sacrifice, by his prowess won over Mahesha and even lived in heaven? Or, if you are unwilling to praise him because you feel that despite being able to do so Arjuna did not win back the kingdom for you, then why not sing my praises, who rescued you from the flaming house of lac, felled the Madra king with a log and threw him into a dry river bed, killed the king-of-kings Jarasandha, conquered the East, killed the mighty Rakshasas Hidimb and Baka earlier and recently Kirmira. All the time it is I who constantly protect you, so why not chant my praises? Never have I seen her, whom you were praising, protect you. And should you not wish to praise me, considering me a glutton, cruel and reckless, then proceed uttering the Pranava ‘Om’ punctiliously. Wasteful speech is a fault and invites evil spirits into the body because of which that person is repeatedly prompted to talk irrelevantly. Whatever such a person eats or does goes to satisfy evil spirits, so say the scriptures. He cannot gain comfort in this world, let alone the next. I am reminding you that the wise always avoid unnecessary speech. Should you still continue talking irrelevantly, it will be our duty to treat you with various medicines.”

Having listened to Bhima’s huge speech—spread out like a bale of cloth—Yudhishthira laughed and said, “Definitely you are without intelligence and have studied the Vedas in vain, for you are not respecting Ambikaa the mother of all creatures. Why are you slighting her for being a woman? Our mother Kunti is a woman too. In what way does she not deserve respect? If Mahamaya, worshipped even by Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, were not there, how could this body of yours be formed? Even the Supreme Lord cannot do without her, for even he depends on her. Vasudeva too worships that transcendent Shakti daily. If I need medical treatment, then so does he. Out of stupidity, do not repeat such words about Maheshvari. If you have any desire at all for happiness, then fall supine on the ground and take refuge in her.”

Bhima said, “Flatterers use every means to bring men under their influence and in such cases not to converse with them is the best medicine. Everyone strives to achieve his own goal. Therefore we too will do only what we wish. With the strength of a thousand elephants, son of Pavana, this Bhimasena will never take refuge with any woman.” Saying this, he began to follow Yudhishthira who went ahead muttering, “This is not good, this is not good.”

After a while Bhima began to stagger and called out, “O best of kings, most wise Dharmaraja! See, I cannot see anymore. What has happened to me?” The king replied, “Bhima, definitely the goddess Maheshvari is angry with you and that is why your sight is destroyed. Therefore, mentally take refuge in her at once. Then, being pleased, she might restore your sight.” Bhima said, “O great king, I know that none can compare to the Devi, but it is to obtain sight of her that I abuse her constantly. Therefore I am now witnessing her power and lying supine, with heart, mind, speech I take refuge in that mother and sing her praises.”

Pleased by the paean he chanted, the goddess who was as dark as Krishna and lovely, appeared before Bhima holding sword, shield, pike and cup in her four hands. Bhima regained his sight and worshipped her, begging her to be pleased with him. The goddess placed Yudhishthira and Bhima in her lap and said, “Do not abuse me again. I know why you did it and although Krishna does not like my expressing anger, I did so because it was necessary. Whenever dharma declines, Hari manifests on earth and so do I to help him. At present he has taken birth as Vasudeva’s son and I have appeared as Nandagopa’s daughter Ekanamsha. Since you brothers represent Krishna’s spirit, you are also my brothers and I shall be known as “Bhima-bhagini,” Bhima’s sister. When you fight in the great war, I will dwell in your arms to destroy the Dhartarashtras. After ruling for thirty-six years you shall leave the world. Then at this pilgrimage spot a mighty demon named Loha will try to kill you, noticing that you are unarmed. I will then blind him while you will proceed to cross the snows and finally sink into the sands. Yudhishthira alone will reach heaven with his body. Where Loha falls a city named Lohana will come up and a portion of me shall dwell there restoring sight to the blind if they worship me on the seventh day of the bright fortnight. In Kali Yuga a devotee of mine named Kela will be born and I shall be called Keleshvari after him. Another excellent devotee of mine named Bailaaka will appear and because of him I shall be renowned in that era in particular. It is here that I shall destroy the demon Durgama and therefore be known as Durgaa. To protect you all I shall dwell in the eastern side of Dharmaaranya. In Kali Yuga one of your descendants, the king of Vatsa shall please me and I shall be known after him as Vatseshvari. By my grace that king shall slay a demoness named Attalaya and a village named Attaalaja shall come up at that spot. There an image of Vatseshvari shall be established. Later Loha shall be reborn and be invincible. Then Vishnu shall incarnate as Budha and destroy him. At that spot a village named Lohaati shall be founded. Another demon named Gaya will be made into a eunuch by me and a village named Gayataada will come up with an image of mine so named worshipped there by eunuchs. Remember me as your sister whenever you face danger. You are as dear to me as Krishna Now proceed to visit all the sacred pilgrimage spots.” Saying this, the goddess vanished. Telling Barbareek to meet them after the exile was over, the Pandavas left to visit the teerthas.

After the exile was over and the armies assembled at Kurukshetra, Arjuna was boasting to apprehensive Yudhishthira that by himself he could rout the enemies in a single day when Barbareek spoke. He said, “One who has performed ascesis and pleased the goddesses in their secret abode Guptakshetra, hear of that person’s incomparable prowess. O kings, not out of mere arrogance, but speaking the truth about my valour, I say that I am not satisfied with the time-span that worshipful Arjuna has mentioned, for it is an unnecessary waste of time. All of you stay here with Arjuna and Keshava while I alone will despatch Bhishma and all the Kauravas in a moment to Yama’s abode. When I am present, no other warrior need take up arms. Should I die, then let others fight. Look upon the might I have obtained by worshipping the goddess and realise the greatness of Guptakshetra and my devotion towards the Pandavas. See, here are my terrible bow, inexhaustible twin quivers and sword gifted by the goddess, because of which I have spoken thus.”

All the warriors present were amazed. Somewhat embarrassed, Arjuna glanced at Krishna who supported Barbareek, “He has spoken justly. In the past, one hears that he had destroyed innumerable demons along with the danava Palaashi in but a moment. But tell us, grandson of Bhima, exactly how do you propose to demolish the Kauravas in a moment, protected as they are by Bhishma, Drona, Kripa, Ashvatthama, Karna, Duryodhana and others, so that we can repose faith in your words.”

“O heroes, if you wish to witness the means, I shall show you. Let Keshava and all present watch.” Saying this, Barbareek swiftly placed one of the vermillion-tinted arrows on his bowstring and shot it. From the arrow-tip crimson ash fell on the fatal spots of both armies—Bhishma’s hair-follicles, Drona, Karna, Shakuni, Dhrishtadyumna and Bhagadatta’s necks, Duryodhana’s thighs, Shalya’s chest, the soles of Krishna’s feet, Shikhandi’s waist, and so on. Only Ashvatthama and the five Pandavas were left untouched. “Now,” said Barbareek, “you have all seen that I have marked the mortal spot of everyone. Next I shall shoot sharp arrows at those spots and by those infallible goddess-gifted arrows they shall fall into the maw of death in a trice. None of you should take up arms. In but a moment I shall demolish all these enemies.”

Amazed, Yudhishthira and all the kings present loudly applauded. But Vasudeva was angered and forthwith beheaded Barbareek with his razor-sharp discuss, to the horror of all present. The Pandavas lamented. Ghatotkacha, crying out, “Alas my son!” collapsed unconscious on the corpse. Meanwhile fourteen goddesses manifested there: Siddhaambikaa, Krodamaataa, Kapaalee, Taaraa, Suvarnaa, Trailokyavijayaa, Bhaaneshvaree, Charchikaa, Ekaveeraa, Yogeshvaree, Chandikaa, Tripuraa, Bhutaambikaa and Harasiddhi. Consoling Ghatotkacha, Chandikaa said, “O Kings! Hear why omniscient Krishna has slain Barbareek. In the past, the earth had approached the gods on Mount Meru complaining of being unbearably burdened. Then at Brahma’s request Vishnu agreed to descend on earth along with the gods to remove Prithvi’s burden. At that time the Yaksha chief Suryavarchaa had lifted up his arms and said, ‘Listen, O gods, I am the storehouse of many flaws, hence when I exist, why should any of you descend on earth? Remain here with Vishnu while I by myself relieve the earth of its burden. I swear in the name of Dharma that there is no need for any of you to incarnate on earth.’ At this, Brahma said in anger, ‘Wicked Yaksha chieftain! What is difficult even for the gods you have boasted arrogantly as achievable by you alone. Fool, because of this you deserve to be cursed. He who boasts of his prowess before his superiors without judging his own and others’ strength and weakness deserves punishment. Therefore, at the time of the commencement of the war to relieve the earth’s burden, Krishna will kill you.’ Thus cursed by Brahma, that Yaksha chief prayed to Vishnu that from birth his mind be set on ascesis for achieving salvation. Keshava granted this and said, ‘Worshippers of the goddess will adore your head as well.’ That Suryavarchaa is this slain Barbareek, you all are the gods, and Krishna is that Hari who has merely fructified Brahma’s curse. Therefore, Krishna should not be held guilty by you for this act.” Krishna confirmed the goddess’ words, adding that he had advised Barbareek in Guptakshetra to worship the goddess because that is the boon he had been given in the presence of the gods.

Chandikaa then poured the nectar of immortality on her devotee’s skull, whereby it became unaging and immortal for all time. That Rahu-like head then saluted everyone and said, “I wish to witness this war. Kindly permit that.” In a thunderous voice Krishna roared, “So long as this earth, the constellations, the sun and the moon exist, you, dear one, will be worshipped in the three worlds. In all the realms of the goddesses you shall be honoured like them. The illnesses suffered by children will disappear on worshipping you. Now be placed atop this hill and witness the war.”

Barbareek’s body was cremated, but his head remained on top of the hill. After the war was over, Yudhishthira praised Krishna for having enabled them to be victorious. This irritated Bhima who said, “It is I, Bhima, who has destroyed the Dhartarashtras. Ignoring me, like a fool why you are singing paeans to Krishna calling him ‘Purushottama’. O Pandava, Dhrishtadyumna, Arjuna, Satyaki, myself—ignoring us you are praising a charioteer. Shame on you!” Arjuna replied, “No, Bhima, do not say this. You do not know Janardana. Neither you, nor I nor anyone else has slain the enemy. During battle I always noticed that before me some person was advancing slaying the enemy. I do not know who that man was.” Bhima said, “There was no other enemy-killer, Partha. Surely you are hallucinating. However, if you do not believe me, let us ask my grandson on the hill who killed the enemy.” Bhima put this question to Barbareek who answered, “I saw but one man fight. On his left he had five faces and on his right only one. The left side of his body had ten hands holding weapons and the right side had four with the discus etc. The heads on the left were crowned with matted hair; that on the right had a glowing crown. The left body was covered in ashes; the right was smeared with sandal paste. The left had a crescent moon, the right the Kaustabha gem. I was terrified. I have never seen such a man.” A shower of flowers fell from the sky with shouts of “Excellent, excellent!” Astounded, the Pandavas touched Krishna’s feet. Bhima hung his head in embarrassment. Krishna said to Barbareek, “O Suhridaya, roam the worlds, fulfilling the prayers of all. Everyone shall worship you. Never abandon this Guptakshetra for it is the best among all sacred places. And also stay in Dehasthali, freeing your worshippers from sin.”

Ashamed, Bhima drew deep painful sighs. Krishna seized his hand and saying, “O Kuru-tiger, come!” took him up on Garuda’s back and flew southwards. Crossing the southern sea and Suvela (Trikuta) mountain, they reached Lanka. Pointing out a lake there, Krishna said to Bhima, “O Kuru-tiger, see this twelve yojanas span of water. If you are a hero, bring up earth from its bottom.” Valiant Bhima immediately jumped from Garuda’s back into the lake and with wind-like speed dove beyond a yojana but failed to find its bottom. Rising from the lake frustrated, he said, “O Krishna, this vast lake is bottomless. Several mighty beasts in it tried to devour me and I have escaped somehow with great difficulty.” Hearing this, Krishna laughed and with his toe upturned that huge lake and told the astonished Bhima, “In the past there was a rakshasa named Kumbhakarna whose head was sliced off by Rama’s arrow. It is the palate of that skull that has taken the form of a lake. Being ancient, it has broken into pieces on my overturning it. Those who attacked you were the Sarogeya gods who are enemies of this world and it was necessary to destroy them cunningly thus. Now they have been shattered against the rocks of Trikuta mountain. Now let us return to the Pandavas who are being threatened by Drona’s son.” Bhima begged Krishna’s pardon for his rude words, which was granted.

Barbareek is worshipped on the new moon day of Shravana and the thirteenth day of the dark fortnight of Vaishakha by lighting a hundred lamps, chanting a hymn in his honour and offering purika cakes.

Khaatu Shyam

(claims to be based upon canto185, sections 1-2 of the Udyoga Parva of the Mahabharata)

Khaatu village is located 16 kilometres from Reengas railway station. King Khatvaanga ruled on the banks of the river Rupaavati and bathed in it daily with his queen. A temple of Shiva was located in the centre of the town where he worshipped daily with river water and grain grown by himself. Ever concerned about the welfare of his subjects, he was just and virtuous. One day his queen complained that she had no jewels to wear. The king told her that only what he grew himself was theirs, but the queen would not be pacified without ornaments.

Finally, the king sent a messenger to Kubera, the lord of wealth, who sent back chests filled with ornaments. Decked in these, the queen accompanied the king to the river on a Monday to bring water to pour on the Shivalinga in the temple. As they dipped the earthen pots in the river, the king’s turned golden but the queen’s melted away. She realised the fruit of her karma.

This river Rupaavati used to flow originally by Hastinapura. Any creature bathing in it was lifted bodily to the other world. The Dharma-king approached Vishnu that as the Kali Yuga was approaching, should all sinful creatures bathe in Rupaavati they would cause mayhem in heaven. Hari smiled and said in that epoch this river would disappear into the earth and be visible only to the virtuous. Further, Krishna would manifest as Shyamdeva at Rupaavati. What was sacred Kaashi in the Satya Yuga would be Khaatu in Kali Yuga.

250 years ago a Kshatriya maiden named Narbadaa used to serve the deity faithfully with water from the pond and bathing with the water daily. One day the deity appeared before her and granted her the boon of appearing at her call and granting her desire. Since then that Kshatriya clan serves the deity and Brahmins of Gauda perform the worship.

Bhima had two beloved sons. His first queen was Ahilyavati, the second Hidimbaa. Ahila’s son was Barbareek who had gifted his head and obtained a boon from Krishna. Hidimbaa’s son Ghatotkacha died fighting heroically for the Pandavas. He had a son named Suhridaya, blessed by Devi Shakti. As he had curly ringlets, he was also called Barbareek. Arriving at the battlefield he boasted of his prowess before Krishna who beheaded him.

Ahilyavati was Naga princess, daughter of the king Vasuki, who used to accompany her father while he worshipped Shiva and Parvati. She was born when Parvati blessed Vasuki that Devaki would be born as his daughter.

Once in a storm all the flowers in the garden were blown away. The next morning Ahilyavati, finding not a single flower on any plant, gathered some fallen on the ground and offered them to the deities. Bhavani was infuriated at this insult to her husband and cursed her to have a dead husband. The maiden begged forgiveness and Vasuki rushed to Mahadeva who assured him that his daughter’s fortune would remain unimpaired. When Bhima was poisoned by Duryodhana and thrown into the river, he floated into the realm of the Nagas. Ahilyavati fainted on seeing his body, saying that this was her husband. Vasuki poured amrita into Bhima’s mouth, reviving him. Ahilyavati told him how he had reached her abode and narrated Bhavani’s curse. Bhima, beset by hunger-pangs, demanded food first and gulped down all the amrita. Vasuki had the remnants fed to cows and since then their urine is counted as pure. Vasuki now begged Bhima to respond to Ahilyavati’s plea—for he was indeed a dead person now alive, as Bhavani had stated her husband would be. Bhima said he would act as directed by his mother and elder brother and wanted to leave, refusing the repeated pleas of Vasuki and his daughter to at least give his word, pledging marriage. Tired out, he fell asleep, in a lovely bungalow in the midst of a garden. Vasuki set guards all around, directing that none should be allowed entry. At midnight the sage Narada arrived and enquired of the guards whether a fair complexioned man had entered the abode of the Nagas, for he had come in search of him. The guard took him to Vasuki who narrated everything. When Bhima met them in the morning, Narada advised him to fulfil Bhavani’s prophecy on the pain of suffering her wrath, and that he would ensure that Kunti and Yudhishthira did not take offence at their permission not having been taken. Bhima agreed to the marriage, which was conducted by Narada. On his way to Hastinapura Narada came across Krishna who told him that for succouring creatures in Kali Yuga Ahilyavati would give birth to his four-armed form.

Bhima and Ahilyavati proceeded to Hastinapura with four mighty escorts provided by Vasuki. On the way they stopped at Panchavati to offer worship to Shiva in his temple. At night a terrible Rakshasi named Ghori appeared, roaring and throwing rocks and trees about. Ahilyavati urged Bhima not to hit a woman, and herself jumped on the ogress, whirled her about by her hair, threw her on the ground, kicked her on the chest and dragged her by the hair to her husband’s feet. Bhima pardoned the terrified demoness who was begging for her life. With a parting kick Ahilyavati bade her leave. The next day Bhima announced his departure for Hastinapura, assuring that he would come whenever she called. Ahilyavati smiled sadly and said she knew he would never come back. She asked him to stay on at least till their son or daughter was born so that the child knew the father. Bhima assured her that it would be a mighty son and that he would definitely return on call. He left for Hastinapura. Vasuki came to visit his daughter and left after putting the guards on alert.

The demoness Ghori told her spouse, the rakshasa Doondaa, about this couple living in the forest. Doondaa assumed the appearance of Bhima and sat down where Ahilyavati was lost in meditation, worshipping Shiva and said, “I have arrived, my queen.” As he sought to hold her hand, she opened her eyes, stood up and stepped back. Flames erupted enveloping the demon and burnt him to ashes. As Ghori came running, she too was burnt up.

Ahilyavati gave birth to a son who waxed mighty immediately after birth, with mighty arms, red eyes, shining curly black hair. Narada came from heaven, named him “Barbareek” and informed Ahilyavati that the Pandavas had been exiled deceitfully for thirteen years. As advised by him, she taught her son to worship Shiva and taught him to perform “japa” since he wanted to meet him.

Once, hearing a lion roar, Barbareek sought it out and rode on its back to his mother. He used to play with the entire pride. One day Ahilyavati showed Barbareek a lion fleeing from a hunter. Barbareek ran after them and challenged him. As the hunter shot arrow after arrow at him, Barbareek caught them all and snapped them. When the hunter was exhausted, Barbareek hit him once with his fist and he fell dead. Barbareek dragged the corpse to his mother who rebuked him for killing a defeated opponent. She taught him the code of Kshatriyas—never to trouble the weak, to protect the defeated, never to let a mendicant leave empty-handed and ever to obey parents.

From the god of fire, Agni, she obtained an indestructible bow that would never miss its target. Agni told Barbareek that the matching arrows he would have to obtain himself from Shiva. Daily this bow and the arrows were to be garlanded in the Shiva temple. Ahilyavati took her son to the realm of the Nagas where Vasuki, her father, gave him Amrita, the draught of immortality, to drink. Daily Ahilyavati would sit on the branch of a tree and teach her son archery. Barbareek faithfully followed every instruction of hers. One day she pointed out to him the top of a mountain as the target and challenged him to hit it. Barbareek shot his arrow with such force that the mountain peak shattered, the wild beasts fled in all directions, and the arrow flew back into Barbareek’s hand. His mother leapt down from the tree and hugged him in joy.

On this mountain lived many demons who were injured when the peak was shattered. Roaring aloud, they ran at mother and son. Ahilyavati alerted her son, who shot a single arrow at them and then watched while she started catching them and throwing them on the ground. Barbareek noticed that she thrashed only those who attacked her, but did not touch the fleeing demons. Returning to her son she asked him to explain why he had shot the arrow without her permission when she had only asked him to be ready. She explained that the opponent must be given the opportunity to make the first move. The Kshatriya never hits first. Touching his head to her feet, Barbareek begged forgiveness and promised never to repeat this mistake.

Koshaasur was the leader of the demons and on hearing of what had happened he was enraged. He proceeded to where Ahilyavati was and insulted her. She gestured to Barbareek who hit him with his fist. The demon attacked him with a sword, whereupon Barbareek kicked him on his chest so hard that he fell far away. Barbareek then caught hold of his legs and tore him into two. Similar was the fate of his general Khadgasur whom Barbareek throttled. The hermits living in dread of the demons were now free of all fear. Delighted, Ahilyavati blessed and embraced her son.

Mother and son worshipped Shiva and Barbareek got immersed in invoking the deity, totally oblivious of the passage of time. Ahilyavati deputed guards around him and sat down, invoking Parvati to grant her son the darshan of Shiva. At this time Vasuki arrived and understood what was happening. He proceeded immediately to Shiva’s abode and bowing at his feet begged him to grant his grandson and his daughter the divine darshan. Manifesting before the meditating mother and son, the divine couple awakened them. Falling at their feet, when Shiva bade Barbareek to ask for a boon, he begged for arrows to match the bow given by the god Agni. Shiva then gave him three arrows and told him that a single arrow would pierce through an entire army, killing all creatures and return to the quiver. Together, the three could destroy the entire creation and none could withstand them. Shiva prescribed a condition, that Barbareek should assist the side which was likely to lose in a war. Shiva blessed Barbareek that no one, not even the lord of creation, would be able to oppose him.

Barbareek used this arrow to destroy Bhil bandits who stole the cows of Phattaa Gujar, with whose milk Ahilyavati used to worship Shiva, and Somasur with his army who tried to ruin the sacred sacrifice performed by sage Harit.

One day the sage Narada arrived and told Barbareek that the great war between Kauravas and Pandavas was to begin in which the former had the larger army while the latter had only Krishna with them. Barbareek then decided that according to his vow he would fight on the side of the weaker side. Narada left, eager to see what Krishna would do now because the side that had Krishna with it was actually the stronger and therefore Barbareek ought to be supporting the Kauravas. That would lead to a fascinating god-versus-devotee encounter that Narada gleefully awaited.

Taking his mother’s permission, Barbareek set out for Kurukshetra. On the way he rested beside a lake at night and sang a paean to Shiva. Hearing this a demoness approached him, disguised as a nymph, and begged him to be her husband. When he refused, she caught hold of his hand. Barbareek invoked his mother for protection as he would not raise his hand against a woman. Flames issued from the saffron mark Ahilyavati had put on his forehead, and consumed the demoness.

The next morning Krishna, disguised as a Brahmin, met Barbareek on the road and asked where he was going. Barbareek proudly announced that he was going to fight in a war and that a single arrow of his would decide its fate. He urged Barbareek to return home, asking how with just three arrows he expected to do anything. Barbareek replied that with one arrow he would win the war as it would slay all soldiers, howsoever numerous. The Brahmin asked him to demonstrate the power of that arrow by shooting down every leaf of an ashvattha tree before them. Barbareek did so, but Krishna had kept one leaf hidden under his foot. When the arrow reached his foot, Krishna became grave understanding that in an instant this youth was capable of making the impossible possible and changing everyone’s destiny. He removed his foot and the arrow, piercing that leaf, returned to Barbareek’s quiver. Krishna revealed his four-armed form, to which Barbareek bowed his head. When asked to beg a boon, Barbareek prayed that this enchanting Shyam form, clad in yellow, be his and the world extol him by that name. That was day of Ekadashi, the eleventh day following the new moon.

The next day Barbareek reached the camped armies and sought for the flautist. He noticed the huge army of the Kauravas and was sure they could not lose the war. A soldier pointed out to him the chariot flying the monkey pennant on which Krishna would be found. Approaching the chariot, Barbareek asked its driver his name and was told it was Muralidhar, the flautist. Saluting him, Barbareek declared that he was Ahilyavati’s son, was of Pandava descent and had come to fight on the weaker side. The Pandavas ran up and embraced Bhima’s son. Krishna now told him that before the battle began it was necessary to perform a ritual to removed all obstacles to Pandava victory and that for this the head of either Arjuna or Krishna or Barbareek—the mightiest three among them—was necessary.

Barbareek laughed and said this was a unique opportunity where Krishna himself was asking for alms, but his innermost desire was to witness the war and this should be granted. Krishna gave his word that Barbareek’s head would be immortal and would be worshipped by the world in Kali Yuga. Catching his hair on one hand, with the other he sliced off his head and placed it in Krishna’s hands. Krishna transformed it into his own likeness and placed the head atop a pole on a hill from where it watched the entire battle. Krishna explained to Arjuna that for the salvation of people in the coming Kali Yuga he had invested that head with a fourth of his sixteen qualities, participating in the battle with the remaining twelve.

After the war in the Pandava camp Arjuna and Yudhishthira ascribed their victory to Krishna. This enraged Bhima who asserted that it was his mace and Arjuna’s arrows that had won the victory. Yudhishthira then told him that to resolve the dispute it was best the enquire of one who had witnessed the entire war. Bhima agreed. Krishna brought down the head from the pole. Everyone was enchanted, finding it was virtually Krishna’s reflection. Krishna bade him to relate to his father whether it was Bhima’s mace and Arjuna’s arrows that had won the war.

That head witnessed every fighter killed by the discus, followed by Bhavaani catching the blood in a skull and drinking it gleefully along with a band of dancing yoginis and Bhairav sword in hand. The Flautist had turned Annihilator. Bhima bowed his head in acknowledgement.

Krishna blessed Barbareek that his head would be a deity in the Kali Yuga granting his devotees their desires and would be invoked with the chanting of “Jai Shri Shyam!” His form would be four-armed and the scent of sandalwood would waft from it. Krishna then summoned Luhaagar, handed him the head, asking him to keep it in the sacred spot of Dagdhsthali. In Kali Yuga Sishupal would be born as an extremely arrogant king because he had lamented while dying that while Krishna had fled from Jarasandh he had never done so from him, thereby casting a slur on his fame. In Rupavati river Sishupal would discover the head where Luhaagar was asked to drop it.

Luhaagar complied and the head of Barbareek was carried down the river to Khaatu, the capital of king Khatvaang, where the river disappeared. The capital too was abandoned. Here a cow would daily pour its milk on the spot where the head lay buried. Hearing of this marvel, the people dug up the head and heard a celestial voice announce that this was an incarnation of divinity blessed by Krishna, the son of Ahilyavati, which should be worshipped in a temple. The people built a temple, kept the head on a throne and worshipped it. The spot where it was found became known as Shyam-kund, the pond of Shyam.

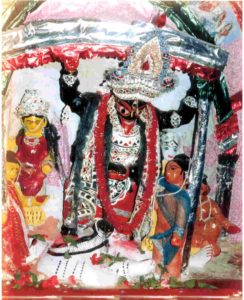

There is an image of Kali in the Lalgola palace temple that is unique. Its four hands are bereft of any weapon. The two lower hands are folded in front (karabadhha), the palm of one covered by that of the other, just as a prisoner’s hands are shackled. From behind, the image is shackled to the wall with numerous iron chains. Kali is black, of terrifying mien, naked, a serpent between her feet, and Shiva a supine corpse before her. This represented to Bankim what Bhaarat, the Mother, had become:

There is an image of Kali in the Lalgola palace temple that is unique. Its four hands are bereft of any weapon. The two lower hands are folded in front (karabadhha), the palm of one covered by that of the other, just as a prisoner’s hands are shackled. From behind, the image is shackled to the wall with numerous iron chains. Kali is black, of terrifying mien, naked, a serpent between her feet, and Shiva a supine corpse before her. This represented to Bankim what Bhaarat, the Mother, had become: