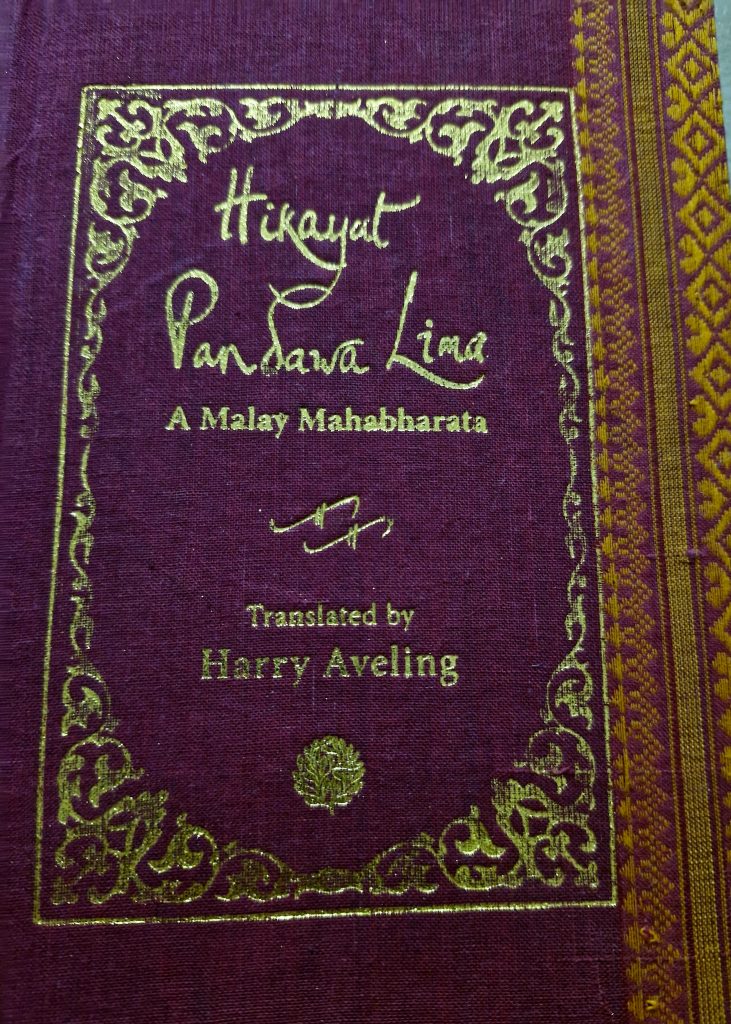

Fascinating variations of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are found in South-East Asian countries. A compendious study of these is yet to be made. Most Ramayana variations were summarised by Fr. Camille Bulcke in his encyclopaedic study of the Rama story in Hindi (cf. English translation by Pradip Bhattacharya, The Rama Story—Origin and Growth, Sahitya Akademi, 2022). Nothing similar exists for the Mahabharata. Now Professor Harry Aveling of Monash University has complemented his translation of Hikayat Seri Rama, the Malay Ramayana (2020) by rendering into English a Malay Pandava Chronicle (Hikayat Pandava Lima, Writers Workshop, Kolkata, 2024, pp. 309, hardback Rs.1200). This is but one of the many versions of the Mahabharata in South East Asia, drawing upon the old Javanese Bharatayuddha (1157-59 CE), Ghatokachasraya and Hariwangsa. Dated vaguely (1350-1700?), the anonymous Hikayat Pandava Lima (HPL) was meant for recitation in the royal court. HPL, Aveling suggests, is a collection of scripts for staging with actors or puppets. The heroic episodes are peppered with erotica and clowning, e.g. Rajuna (Arjuna) having fun at the expense of his attendants Semar and Chemura.

Claiming to relate in Malay the Javanese story of their ancestors, the Indian source is obvious. Mantras are in Javanese. The Islamic influence is apparent in Darmawangsa’s (Yudhishthira) infallible supreme-weapon named kalima sada (kalima shahadah, declaration of faith) and in scribal notes that resurrection and rebirth are false. Pandawas have talismanic weapons: Rajuna’s pasupati arrow (not the Gandiva bow) and Bima’s (Bhima) panchanaka, his long sharp nail that pierces fatally, besides a massive mace. The influence of Telegu, Tamil and Malayalam folk-tales is clear in several episodes. Replete with adventures and romance, the flavour is much like that of the Kathasaritsagara (c.11th century) and Dashakumaracharita (c.8th century). The publisher Ananda Lal’s list of original Sanskrit names of major characters is extremely helpful in navigating through the plethora of persona peopling the chronicle. Strangely enough, Dhritarashtra, Gandhari, Ulupi, Chitrangada do not feature.

Eveling seeks to convey the Malayan syntax by replacing the word maka, which acts as a bridge between sentences, by the double forward slash (//) hoping “to show the self-contained lines of prose that the word marks off…allow the reader the progress of the text in a slow and aesthetic manner.” Otherwise, it would become a series of staccato sentences.

Eveling splits HPL into three parts: (1) Games of Love and Chance; (2) The Great War and (3) After the War. Beginning in media res with the dice game (as Satyajit Ray had planned to begin his film on the Mahabharata), the chronicle’s last part is the most novel, dealing with Rajuna’s (Arjuna) obsession with Duryudana’s (Duryodhana) widow Banuwati (Bhanumati) and his duel with his thousand-handed namesake Rajuna Sarabahu. Part One draws heavily upon the highly popular Telegu tale of Abhimanyu’s (Bimanyu) love for Sasirekha (Satya Sundari) depicted in shadow puppetry (Tholu bommalata), Yakshagana and Kuchipudi.

There are significant departures from the Mahabharata. Rajuna has two wives: Draupadi and Serikandi (Shikhandi) who swears to fight for the Pandavas. Rajuna turns into an inveterate philanderer. On Duryudana’s command Sangkuni (Shakuni) transforms into dice and Arya Manggala becomes the gambling table. After losing the dice-game, Darmawangsa sends Draupadi back to Inderpasta (Indraprastha) where she remains till the Pandavas return from exile. Darmawangsa has to groom horses. Bima is the gatekeeper who never opens the gate so that people unable to access the river relieve themselves inside filling Duryudana’s palace with stink. Rajuna is the gardener seducing all Duryudana’s concubines and his wife Banuwati. Duryudana, furious, turns to Drona who advises that the Pandavas be ordered to dive into the river to recover an arrow. A dragon living there swallows them but Bima rips open its belly and they proceed to the city of Merchunegara ruled by Wurgadewa. The entire forest-exile is omitted. Draupadi and Kichaka are absent. The Pandavas are disguised as the king’s priest, chief butcher, female dress-maker and grooms. The cross-dressing Rajuna seduces the queens as well as wives and daughters of all ministers, ignoring Darmawangsa’s disapproval. None of the queens are willing to be with Wurgadewa thereafter! The sharing of betel quid is a major step in seduction. Elaborate descriptions of beautiful heroines compared to a variety of flowers abound.

Bimanyu’s love-sickness for Krishna’s daughter Satya Sundari is an elaborate episode filled with romantic descriptions of nature and of both protagonists. While following the Telegu tale, it introduces a horrific gigantic goddess Durga seated on a golden throne surrounded by goblins, skulls and blood, recalling the Bheel Bharata. She who appoints Gatotkacha to fulfil Bimanyu’s desire. Later, Bimanyu falls madly in love with Dewi Utari (Uttara) daughter of Maharaja Mangaspati of Wirata, enraging Satya Sundari, which reminds us of Draupadi’s anger when Subhadra arrives as Arjuna’s new bride. She gets reconciled after Bimanyu recites an obscene spell taught by Rajuna. Krishna has no objection, as he himself has twenty wives!

After thirteen years, ordered by Indera (Indra) to return to Inderapasta, the Pandavas arrive and find Karna has taken Kunti to Astinapura (Hastinapura). Setyaki (Satyaki) is Kunti’s brother. The Korawas are 107 brothers. Kunti bids Duryudana give Astinapura to the Pandavas as it is their inheritance, but he refuses.

The Great War is preceded by another that is unique to this chronicle. Wurgadeva demands that Darmawangsa hand over Utari and Satya Sundari to him as they are reincarnations of his late wife. A battle occurs in which Krishna, Baladewa and Gatotkacha join the Pandavas. Rajuna kills Wurgadeva. Commanded by Betara Guru (the supreme deity), the Pandavas agree to the slain being resurrected by the sprinkling of Sempayang Merta Jiwa water (mritasanjivani). Similar innovations occur in the apocryphal Dandi Parva where Pandavas and Kauravas jointly fight Krishna over Urvashi transformed into a mare; in Kavi Sanjay’s 15th century Bengali Mahabharata in which Draupadi and the Yadava women rout the Kauravas after the killing of Abhimanyu; and in Tamil tales of Arjuna’s philandering helped by Krishna.

The Kurukshetra war mostly follows the Mahabharata, omitting the Gita and Krishna’s cosmic form. That occurs only when Duryudana tries to capture him during his peace embassy. On the battlefield when Rajuna does not wish to fight, Krishna is amazed. Thereupon Darmawangsa goes afoot to Bisma (Bhishma) and obtains his blessings for victory. The fallen Bisma bids Rajuna provide a mat, rejecting Duryudana’s golden five-layered mat. Rajuna spreads out arrows on which Bisma gladly lies. When Bahgadata (Bhagadatta) kills Rajuna, Krishna resurrects him with his wijaya kusama (victory flower). Karna breaks Bimanyu’s bow and weeps over his corpse. After Gatotkacha’s death his mother Arimbi (Hidimba) weeps with Kunti and Draupadi and then plunges into his pyre.

Moving romantic interludes are introduced featuring Karna and his wife Sinta Kunti, Salya and his queen Satyavati before their deaths. Karna’s chariot is destroyed instead of getting bogged down. Salya tells Sakula (Nakula) how Darmawangsa can kill him. Battle-descriptions are formulaic and become tedious, with elaborate accounts of chariots, horses, flags, weapons, blood and gore and heroes running amok. Those victorious are invariably presented a full set of clothes and ornaments by the king. The mass-mourning of the Stri Parva is replaced by Satyavati’s lament. She commits suicide over Salya’s corpse, followed by her maid Skanda. Unable to bear the pain of his shattered thighs, Duryudana begs the Pandavas to kill him but Bima’s club-blows fail because the deities decree that death will come only after the Pandavas have been beheaded. This occurs after Bambang Sutomo (Ashvatthama) brings him the head of Panji Kumara, son of Darmawangsa. Bima skins Sutomo alive.

Sangkuni (Shakuni) resurrects after Bima kills him by virtue of his magical panji suata. With the remaining Korawa troops he builds a fortress in Inderaguna forest. Krishna bids his son Parjaman to kill Sangkuni but he is afraid, whereupon the Pandawas give him their talismans. Sangkuni transforms into a second Mount Imaguna, is attacked by the Pandawas and mortally wounds Darmawangsa by piercing his shadow (in a Malayalam tale Duryodhana does this to the Pandavas). Sadewa kills Sangkuni and drops his ashes into the sea so that he cannot resurrect.

The post-war portion is filled with unique tales. Bima kills Dursana, Bahgadatta and Karna’s widows but Rajuna saves Banumati and marries her. The Pandavas return to Mertawangsa while Rajuna settles in Astinapura with Banumati. Here Duryudana’s spirit possesses him and he fights against his brothers. Darmawangsa exorcises the spirit whereupon reconciliation occurs, but he curses Rajuna with leprosy. With Banumati he lives in a hut in Inderaguna forest. Krishna seeks him out but Rajuna refuses to return as he is grieving for his wife Serikandi. Krishna advises him to take Ratnawati, wife of hundred-headed Rajuna Sasrabahu (Arjuna Sahasrabahu), who is like Serikandi. In an elaborate battle Sasrabahu is killed only when Rajuna severs a tiny head hidden behind his left ear. This has a parallel in the folk tradition of one of Ravana’s heads being a donkey’s. Ratnawati kills Rajuna but Krishna resurrects him with a wijayamala flower. To stop the fleeing Ratnawati, Rajuna shoots off her garments and captures her. Sasrabahu is resurrected by Narada on orders of Begawan Guru so that he can complete worshipping him. Krishna takes Rajuna and Banumati back to Mertawangsa where Darmawangsa forgives and cures him.

The massacre of Yadavas is changed into a celebration on the sea-beach by them and the Pandawas during which Krishna and Rajuna dry up the sea-bed to provide a playfield for wives. Enraged, Singabiraja, king of ghosts and rakshasas living in mid-ocean, kidnaps Parkasti (Parikshit). Rajuna beheads him and rescues his grandson. After crowning Parikasti, the Pandawas are told by Narada that Begawan Guru and Indera have summoned them to heaven. So, Darmawangsa stabs himself with the weapon bajrima. Bima tells Narada to kill him by hitting under his ear. Instead, he breaks Bima limbs with his club as punishment because he had caused pain to so many and only then kills him. Rajuna is stabbed by the pasupati; Sakula and Sadewa stab themselves. Draupadi, Subadra, Banuwati and Ratnawati plunge into the pyre. Parikasti places the urns containing the ashes in a temple.

The chronicle concludes with the exhortation to omit whatever offends and expand whatever pleases. “I have done what I could” says the chronicler.