FOUR PARABLES

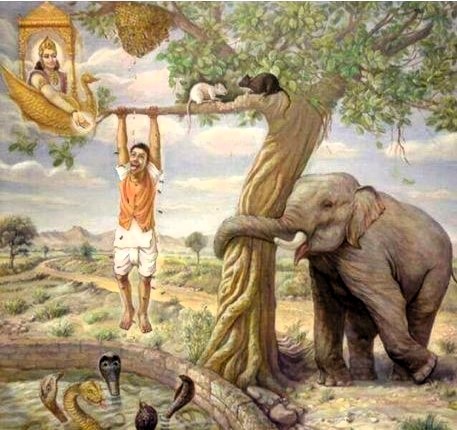

The parable of the Kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree, narrated by Sri Ramakrishna.[1]

আয়ে মন বেড়াতে যাবি

কালী কল্পতরুতলে গিয়া

চারি ফল কুড়ায়ে খাবি—রামপ্রসাদ সেন

“Come my mind to go a-roaming.

Going to Kālī the Wish-Fulfilling-Tree

Pick up and eat four fruits.”—Ramaprasad Sen (mid-18th century, West Bengal)

Into a room full of children at play walks the proverbial uncle, back from the city, who, of course, knows better. Laughing at their preoccupation with make-believe games, he asks them to lift up their eyes and go out to the massive banyan tree, which will grant them whatever they wish—the real stuff! The children do not believe him and remain busy with their toys. The uncle shrugs and leaves. And then they rush out, stand under the branches of this huge tree that cover the sky and ask for what all children crave: toys and sweets. In a flash they get what they want, but along with an unexpected bonus: the built-in opposite of what they wished for. With toys they get boredom; with sweets tummy-ache. Sure that something has gone wrong with their wishing, the children ask for bigger toys and sweeter sweets. The tree grants them their wishes and along with them bigger boredom and bigger tummy-ache. Time passes. They are now young men and women and their wishes change, for they know more. They ask for wealth, power, fame, sexual pleasure—and they get these, but also cupidity, insomnia, anxiety, and frustration/disease. Time passes. The wishers are now old and gather in three groups under the all-encompassing branches. The first group exclaims, “All this is an illusion!” Fools, they have learnt nothing. The second group says, “We are wiser and will wish better next time.” Greater fools, they have learnt less than nothing. The third group, disgusted with everything, decides to cop out and asks for death. They are the most foolish of all. The tree grants them their desire and, with it, its opposite: rebirth, under the same tree. For, where can one be born, or reborn, but within this cosmos!

All this while one child has been unable to move out of the room. Being lame, he was pushed down in the scramble and when he dragged himself to the window, he was transfixed watching his friends make their wishes, get them with their built-in opposites and suffer, yet compulsively continue to make more wishes. Riveted by this utterly engrossing lila of desire and its fruits, a profound swell of compassion welled up in the heart of this lame child, reaching out to his companions. In that process, he forgot to wish for anything for himself. In that moment of spontaneous compassion for others, he sliced through the roots of the cosmic tree with the sword of non-attachment, of nishkama karma. He is the liberated one, the mukta purusha.

In Anti-Memoirs Andre Malraux writes that in Varanasi an Indian suddenly came up to him and said, “Mr. Malraux Sahib, would you like to listen to a story?” Taken aback, Malraux muttered that he was going to an official meeting. “But this is a very good story,” was the insistent reply. Malraux, perforce, agreed and here is the story he heard:

Narada, the itinerant divine sage roaming the three worlds, sowing seeds of discord and inveterate experimenter, goes up to Vishnu and demands that Maya be explained to him. Vishnu is silent. Narada is not one to be denied. He insists so persistently that the god has to answer him. “Maya cannot be explained, it has to be experienced,” he says. “If you can’t explain what you create, then I won’t believe in you,” retorts the never-say-die sage. Quickly deserting his serpent couch—for the fate of gods in whom humans do not believe is shrouded in uncertainty–Vishnu beckons him to follow. Walking together, they reach a desert where Vishnu sits down under a tree and exclaims, “I am so tired, Narada! Take this lota and get me some water from that oasis. When you return I will explain Maya to you.” Eager to plumb the mystery, Narada speeds off to the oasis and finds a well there beside a hut. He calls out, and a lovely girl opens the door. Looking into her eyes, Narada is reminded of the compelling eyes of Vishnu. She invites him in and disappears indoors. Her parents come out and greet the guest, requesting him to rest and eat after his journey through the burning sands before he returns with the lota of water. Thinking of the lovely girl, Narada agrees. Night falls, and they urge him to leave in the cool morning. Awakening in the morning, Narada looks out and sees the girl bathing beside the well. He forgets about the lota of water. He stays on. The parents offer him their daughter’s hand in marriage. Narada accepts, and settles down here. Children arrive; the parents-in-law die; Narada inherits the property. 12 years go by. Suddenly the floods arrive–floods in the desert! —His house is washed away. His wife is swept away. Reaching out to clutch her, he loses hold of his children who disappear in the waters. Narada is submerged in the floods and loses consciousness. Narada awakens, his head pillowed in someone’s lap. Opening his eyes he gazes into the eyes of Vishnu, seated at the desert’s edge under that same tree, those eyes that remind him of his wife’s. “Narada,” asks Vishnu, “where is the lota of water?” Narada asked, “You mean, all that happened to me did not happen to me?” Vishnu smiled his enigmatic smile. [2]

The Drop of Honey

After the Kurukshetra holocaust, when the blind Dhritarashtra bewails the unjustified misery thrust upon him and turns to Vidura for consolation, this son of Vyasa and a maidservant narrates a gripping parable that provides yet another clue to understanding our existential situation[3]:

Take a certain Brahmin who loses himself in a dense jungle filled with wild beasts. Lions and tigers, elephants and bears…Yelling and trumpeting and roaring…a dismal scene to frighten even the god of death, Yama. The Brahmin is terror-stricken. He horripilates. His mind is a bundle of fears. He begins to run, helter-skelter; he looks right and left, hoping to find someone who will save him. But the fierce beasts—they are everywhere—the jungle echoes with their weird roaring—wherever he goes, they are there, ahead of him.

Suddenly he notices that the fearful forest is swathed in a massive net. In front of him, with open arms, is a horrendous-looking female. Also, five-headed snakes hiss at him—tall snakes, their hill-huge bodies slithering up to the sky.

In the middle of the forest is a well covered with grass and intertwining creepers. He falls in that well and dangles there, clutched by a creeper, like a jackfruit ripe for plucking. He hangs there, feet up, head down.

Horror upon horror! In the bottom of the well he sees a monstrous snake. On the edge of the well is a huge black elephant with six heads and twelve feet hovering at the well’s mouth. And, buzzing in and out of the clutch of creepers, are giant, repulsive bees surrounding a honeycomb. They are trying to sip the deliciously sweet honey, the honey all creatures love, the honey whose real taste only children know.

The honey drips out of the comb, and the honey drops fall on the hanging Brahmin’s tongue. Helpless he dangles, relishing the honey drops. The more the drops fall, the greater his pleasure. But his thirst is not quenched. More! Still more! ‘I am alive!’ he says, ‘I am enjoying life!’

Even as he says this, black and white rats are gnawing the roots of the creeper. Fears encircle him. Fear of the carnivores, fear of the fierce female, fear of the monstrous snake, fear of the giant elephant, fear of the rat-devoured creeper about to snap, fear of the large buzzing bees…In that flux and flow of fear he dangles, hanging on to hope, craving the honey, surviving in the jungle of samsara.

The jungle is the universe; the dark area around the well is an individual life span. The wild beasts are diseases. The fierce female is decay. The well is the material world. The huge snake at the bottom of the well is Kala, all-consuming time, the ultimate and unquestioned annihilator. The clutch of the creeper from which the man dangles is the self-preserving life-instinct found in all creatures. The six-headed elephant trampling the tree at the well’s mouth is the Year—six faces, six seasons; twelve feet, twelve months. The rats nibbling at the creeper are day and night gnawing at the life span of all creatures. The bees are desires. The drops of honey are pleasures that come from desires indulged. They are the rasa of Kama, the juice of the senses in which all men drown.

This is the way the wise interpret the wheel of life; this is way they escape the chakra of life.

Dhritarashtra, of course, misses the point Vidura is making: man, literally hanging on to life by a thread and enveloped in multitudinous fears, is yet engrossed in the drops of honey, exclaiming, “More! Still more! I am alive! I am enjoying life!” And, like the blind king, we tend to miss the point too. Ignoring the law of karma, taking that other road, we fall into the pit and rale; but inveterately, compulsively, perversely, strain every sinew to lick the honey.

The Buddha figured it forth in a characteristically pungent image:

Craving is like a creeper,

it strangles the fool.

He bounds like a monkey, from one birth to another,

looking for fruit.[4]

If heeded, the doctrine of karma becomes a powerful instrument for building character, maintaining integrity and establishing a society that functions not on matsya nyaya [the big devouring the small] that celebrates individualism, but on dharma that upholds society and the world itself.

Determination & Free will

The whole point of comprehending this doctrine lies in perceiving that the much-vexed controversy over determination and free will is resolved if seen in perspective. Let us, once again, take recourse to a story to understand this complicated issue.[5]

Two friends, Shyam and Yadu, lived in a village. Shyam was an ambitious go-getter, and Yadu a happy-go-lucky, ne’er do well. Keen to know the future, they approached a hermit who lived apart in the forest. After much persuasion, he agreed to look into the future and tell them their fates. After a year, he said, Shyam would become a king, while Yadu would die. Returning to the village, the shocked Yadu turned to prayer and began leading an exemplary life. Shyam, immediately on reaching the village, started throwing his weight about, grabbing whatever he fancied from others, threatening anyone who dared to protest, vociferously announcing that soon he would be their king.

A year passed by. Shyam sought out his friend and asked him to help pick the site for his palace. As they walked along the river bank, Shyam stumbled over something and fell. Picking himself up, he found the mouth of a jar protruding from the sand. Digging it up, he found it full of golden coins. Hearing his shouts of celebration at finding such treasure, a robber ran up and tried to snatch the jar. Yadu rushed to Shyam’s help and clutched on desperately to the robber’s leg. Unable to tackle the joint resistance of both friends, the infuriated robber stabbed Yadu on his arm and ran off.

Days passed. Yadu did not die; Shyam found himself still no king. So, they went off to the forest and hunted out the hermit. Confronting him, they demanded an explanation for the failure of his prophecy. The hermit went into meditation and then explained: the conduct of each of them had altered what was fated. Yadu’s austerity and prayers had reduced the mortal blow into a stab injury. Shyam’s tyrannical conduct had reduced the king’s crown to a jar of gold coins.

Fate, therefore, is altered by the individual’s choice of the path. Those that have eyes can see; those that have ears can hear. To develop this intuitive sense one has to dive deep, beyond the superficial sensory perception to the manas and cultivate living in that peace within, that pearl beyond price.

[1] Pradip Bhattacharya: “Desire under the Kalpataru,” Jl. of South Asian Literature, XXVIII, 1 & 2, 1993, pp.315-35 & cf. P. Lal’s Introduction to Barbara Harrison’s Learning About India (1977).

[2] P.Lal: Valedictory Address in Mahabharata Revisited (Sahitya Akademi, 1990, p.291-302–papers presented at the international seminar on the Mahabharata organized by the Sahitya Akademi in New Delhi in February 1987).

[3] P. Lal: The Mahabharata (condensed & transcreated, Vikas Publishing House, New Delhi, 1980, p. 286-7)

[4] P. Lal: The Dhammapada, op.cit. p.157.

[5] Related by Prof. Manoj Das in an address at Sri Aurobindo Bhavan, Calcutta, in 2000

Review of the Anushasana Parva

Yudhishthira’s Questions and Bhishma’s Answers

Suganthy Krishnamachari

The Book Review, Feb. 2024

THE MAHABHARATA OF VYASA: THE ANUSĀSANA PARVA | (VOLUME 13) By Veda Vyasa.

Translated from the original Sanskrit by Pradip Bhattacharya. Writers Workshop, 2023, pp. 1256, Rs. 3000.00

The Mahabharata of Vyasa: The Anusāsana Parva, translated by Pradip Bhattacharya deals with Yudhishthira’s questions to Bhishma and the latter’s answers. It also has Uma’s questions to Shiva and his answers to her.

Bhishma is not perfect, is a flawed character himself. When Chitrangada, son of Shantanu by Satyavati died, his brother Vichitravirya ascends the throne. Bhishma does not want the family line to end. He could well have approached a royal family for a bride for the young king. But instead, he abducts three princesses as brides for his brother. It is ironic, therefore, that in the Anusāsana Parva, he tells Yudhishthira that swayamvara is an excellent form of marriage for Kshatriyas, and condemns marriage following abduction (rakshasa type of marriage) as adharma. And yet, he stopped the swayamvara of the three princesses and abducted them. In the Anusāsana Parva, he talks of the respect that we must show to wife, mother, elder sister and so on. How then does one explain his inaction when Draupadi was being disrobed? The Anusāsana Parva shows us what a bundle of contradictions Bhishma was.

These are among the many verses Bhattacharya quotes, before translating them. The reader will find this highlighting of important shlokas in Bhishma’s discourse useful. It makes the book a ready reckoner for those looking for specific topics in the Anusāsana Parva.

In Section 122, Verse 28, Bhishma says that if someone grants freedom from fear to all beings, then he is granted freedom from fear of all beings. Here Bhattacharya quotes the verse:

abhayam sarvabhutebhyo yo dadati dayapara

abhayam tasya bhutani dadatity anushushruma.

It was Bhattacharya’s reproduction of the original verse that caught this reviewer’s eye and helped make the connection to Vibhishana Saranagati. In Valmiki Ramayana, when Vibhishana arrives at Rama’s camp, Rama says:

sakrd eva prapannaya tavasmi iti ca yacate

abhayam sarva bhutebhyo dadami etad vratam mama

If a person surrenders to Rama just once, then he will ensure protection from all beings for that person, promises Rama. This Ramayana verse is often quoted in Visishtadvaita as proof of the efficacy of surrender. The idea is expanded

in the Anusāsana Parva, where all beings grant freedom from fear to a practitioner of ahimsa. The verbatim quoting of verses, even while providing translations, makes Bhattacharya’s book useful for researchers, looking for cross-references.

Bhishma has some practical advice for Yudhishthira about the need to care for tanks, which present-day rulers and administrators would do well to read, for in the modern world water bodies are being increasingly lost to urbanization.

Apart from Bhishma’s talk on dharmic practices, there is also some science in the Anusāsana Parva. In Section 110, verse 17, Bhishma warns against seeing the rising or setting sun or the midday sun directly. Never look at the sun in an eclipse or its reflection in water, he warns. Science tells us that looking at the sun directly harms the eyes. And even during an eclipse, one has to view the sun only through eclipse glasses or a telescope fitted with a special purpose solar filter. Seeing the sun’s reflection in water or snow can cause photokeratitis, when reflective UV rays result in

blindness.

Anusāsana Parva gives some interesting names of Vishnu, which one does not find in the Vishnu Sahasranamam. Here are a few: Yugantakaraa: Yuga-ender; Shiva pujya: adored by Shiva; Bhutabhavya bhavesha: past, present and future; Samkrta: piercer; Sambhava: source; Brihaduktha: loudly lauded; Jvaradipathi: lord of fever. The Anusāsana Parva also gives 1008 names of Shiva.

In Section 119 Bhishma lays down what we know as the golden rule: do unto others as you would want them to do unto you.

Bhattacharya’s translation is in verse form, and therein lies its appeal. As GK Chesterton said, ‘… The soul never speaks until it speaks in poetry…In our daily conversation, we do not speak; we only talk.’ Reading Bhattacharya’s translation is like listening to Vyasa speak to you through English verses, with Sanskrit verses interwoven into his narrative.

Bhattacharya often gives a Sanskrit name or epithet and then gives its meaning in English alongside. But the

flow of the translation is never impeded because of this bilingual presentation. This kind of presentation, in fact,

gives us an idea of the richness of Sanskrit. While agni means fire, it isn’t the only Sanskrit word for fire. And it helps when Bhattacharya writes—pavaka: bright agni; chitrabhanu: variedly radiant agni; vibhavasu: resplendent agni; hutashana: oblation eater agni. Had he just used fire instead, the translation would have been bland. In some cases, he retains original Sanskrit words like maha, for example, which finds a place in the Oxford dictionary. So, we have maha fortunate, maha energetic, maha souled, maha mighty (section 2, verse 9). No qualifying English adjective or modifying English adverb is used. And one must admit that ‘maha fortunate’ and ‘maha energetic’ read better than ‘very fortunate’ or ‘very energetic’. Sometimes the translator retains Sanskrit words and adds some suffixes as he does with puja, namaskar and pranam. In these cases he adds an ‘ed’ at the end of each word (example puja-ed, pranam-ed), and this sounds rather odd. And horribler than the horriblest (Section 148, Verse 49) can do with some rephrasing.

Bhattacharya’s is a monumental work, splendid and impressive, and would be a great addition to any library.

Suganthy Krishnamachari is a Chennai-based freelance journalist, and has written articles on history, temple architecture, literature, mathematics and music. Her English translation of RaKi Rangarajan’s Naan Krishnadevaraya, and Sujatha’s Nylon Kayiru were both published by Westland Publishers.

THE EPIC AND THE NATION

G.N. Devy: Mahabharata: The Epic And The Nation. Aleph, New Delhi, 2022, pp.142, Rs.499.

It is a testimony to the firm foundations upon which the Mahabharata (MB) rests in India that the traumatic Covid pandemic, which generated so many new phenomena, led Professor G.N. Devy to ruminate on the significance of Vyasa’s mahakavya for the country. His proposition: while the myths we live by lie in the Ramayana and the MB, the West draws upon religious texts, not epics. He asks, why has the caste-split land yet to become anation, “a substantially homogeneous people, despite its exposure to the epic for thousands of years?”

Devy covers an extensive expanse from genetics (David Reich’s Who We are and How We Got Here) to linguistics (David Anthony’s The Horse, The Wheel, and Language, Maheswar Neog’s Essays on Assamese Literatures) to literary theory. For him, Indo-Iranians entered the subcontinent with the horse-and-chariot and mingled with Out-of-Africa southerners to produce the MB culture, shifting from pastoral to agrarian, urban and feudal society. MB combined the mythic and historical pasts as a history marked by “assimilation, synthesis, combination, acceptance and moving forward without exclusions (p.72).” Its great success lies in “making alive two powerful symbols, the wheel and the horse…for future generations.” (p.93). “Its mesmerising appeal is its ability to use history to enliven myth…a veritable mine of ideals of courage, moral truth and liberation.”

Devy’s dissertation rises to several peaks. He is one of the few who realise that the MB was a watershed in socio-political thought. Wandering rhapsodes (sutas) brought to the general public, including the depressed classes and women, scriptural ideas, mystic insights and philosophical ruminations that had been the privilege of priesthood and royalty so that “It became the non-Brahmin’s book of religion (p.106).” To Devy the MB embodies our civilization’s “great negative capability” (p.109), comfortable with multiple beginnings, no definite end, many diverse strands of life and thought, no rigidity of caste structure. We meet bloody Brahmins (Parashurama, Drona, Kripa, Ashvatthama); Kshatriya Vishvamitra becomes a Brahmin, creates new celestial bodies, has Vasishtha’s son killed by turning a raja into a rakshasa, even steals a dog’s haunch from an untouchable for food. None of the protagonists are true-blooded Kshatriyas. After Parashurama’s massacres of Kshatriyas, the class was regenerated by Kshatriya women approaching Brahmins. The Lunar Dynasty itself progresses through Raja Yayati’s sons by Brahmin Devayani and Asura Sharmishtha. Vyasa, born of sage Parashara forcing himself on a fisher-girl, engenders Dhritarashtra and Pandu. The Pandavas’ fathers are unknown, as Duryodhana scoffs publicly. Therefore, Arjuna’s quandary over engaging in a war leading to miscegenation is entirely questionable and ought not to need elaborate philosophical discourse to be dispelled. Devy feels this concern was inserted later because the story brings together tribes, cultivators, herdsmen, “descendants of the society that had created Sindhu culture…a new language, better methods of warfare, and a different pastoral culture.” He refers to the Andhra “Vyasa community that has preserved its genetic identity through strict endogamy over the last 3000 years” as an example of the obsession with avoiding caste-intermixing. His claim about the Gita being “seamlessly woven into the epic-text” is questionable because at its end the Bhishma Parva continues seamlessly from where the text was interrupted by the Gita.

The MB did not avoid contemporary philosophical debates as Devy claims (p.78). Gleaning is explicitly extolled over Vedic yajna, a righteous meat-seller and a housewife over an ascetic Brahmin. Character, not birth, makes a Brahmin. Preservation of life and social order is preferred to blind adherence to truth. The eight-fold path of moderation is voiced and there are references to Jains and Charvakas too. Yudhishthira’s grand horse-sacrifice is shamed by a mongoose who glorifies a gleaner’s gift instead. To cap it all, in a supreme tour-de-force, Yudhishthira himself reviles the gods as well as Dharma itself in the final book.

A peak insight of Devy’s is that Kunti is an unparalleled heroine in the literary world. Kunti, her abandoned son Karna and her nephew Krishna occupy the heart of the story. She ushers Vedic gods into the Mbh (p.60). However, Devy overlooks how it is Kunti’s Yadava blood that rules after the Kurukshetra War, not the Kuru dynasty. Parikshit, grandson of Arjuna and his maternal Yadava cousin Subhadra, rules in the Kuru capital Hastinapura, not the elder Yudhishthira’s son Yaudheya or Bhima’s Sarvaga. Vajra, Krishna’s great-grandson, rules in Indraprastha of the Pandavas. Satyaki’s grandson Yugandhara rules near the Sarasvati and Kritavarma’s son in Martikavat, both Yadavas. So, was Krishna’s game-plan to replace Kuru by Yadava hegemony?

Devy points out that Arjuna alone, Rama-like, strings the Kindhura bow Shiva gave Drupada (vide the Southern recension). As Brihannada he parallels Shiva’s Ardhanarishvara (male-female) form as well as his dancer role. Not only does he become a eunuch, but he also hides behind trans-gender Shikhandi to kill Bhishma. Arjuna sees the trident-wielder preceding his arrows and felling the targets in Kurukshetra. Actually, Shiva’s presence is heralded early when Indra insults Shiva and Parvati playing dice and is condemned to take human birth along with four previous Indras.

Devy provides an important insight: the two towering figures on either side, Bhishma and Krishna, both 8th sons, do not fight for themselves but for the Dhartarashtras and the Pandavas respectively. Further, blessings, curses and supernatural interventions are used as devices (deus ex machina) to move the plot along. Even demons intervene to dissuade Duryodhana from committing suicide. Vyasa himself intervenes often in person to change the course of events.

Devy does sink into some troughs though. Ganesha snapping off a tusk to transcribe Vyasa’s dictation is not in the MB (p.10), nor is Gandhari making Duryodhana’s body invulnerable (p.68). What the MB does have is Shiva making Duryodhana’s torso adamantine and Parvati making his lower part lovely and delicate as flowers. Satyavati’s son by Shantanu was Chitrangad, not Chitravirya. Kunti is not chosen to wed Pandu but chooses him (p.59) and is not born because of any blessing (p.71). Jayadratha did not expose himself to Draupadi in the dice-game-hall (fn p.70); that was Duryodhana. Bhrigus are not Kshatriyas but Brahmins (p.61). Nowhere does the MB state that Varuna as Vayu became Bhima (p.60). How is Saranyu equated with Cerberus the three-headed dog guarding hell (p.35)? Saranyu is not the dark, as Devy writes in one place, but the dawn as he correctly states elsewhere. It is not that no attempts have been made to collect regional translations for comparison (p.21). In 1967 M.V. Subramanian ICS documented variations from Vyasa in the South Indian languages plus Bhasa, Bhatta Narayana, Magha and Bharavi. The IGNCAshould now cover all regional languages. The 11 pages long genealogy at the end fails to engender a sense of “a seamless combination of myth and history” as claimed.

Devy overlooks the remarkable motif of the Yadavas, descendants of the disinherited eldest son Yadu, ultimately regaining dominion. Nahusha’s eldest son Yati turns sanyasi, so the younger Yayati inherits Khandavaprastha. He disinherits four elder sons (Yadu etc.) in favour of the youngest Puru. In Hastinapura, Pratipa’s eldest son Devapi is disinherited because of a skin ailment.The younger Shantanu is enthroned. He bypasses his eldest son Bhishma for the younger stepbrothers. The elder Dhritarashtra being blind loses the throne to his step-brother Pandu. Yudhishthira, the eldest, is tricked into exile by his younger cousin Duryodhana who rules. Another key feature missed is the theme of parricide and fratricide is—a reason for the narrative’s continuing appeal through the ages.

Devy accepts Abhinavagupta’s assertion that the MB’s prevailing emotion is “shanta, empathetic detachment”. In World of Wonders (2022) Hiltebeitel argued convincingly that it is an epic of wonder, adbhuta being the rasa mentioned most frequently. Devy’s identification of Yama with Dharma is questionable. Kunti does not summon Yama for a son, as he claims (p.51), but Dharma as Pandu wants his first son to be beyond reproach. All of Yudhishthira’s interactions are with Dharma, not Yama. It is Dharma whom Animandavya curses to be born as a Shudra (Vidura). Yama as god of death first appears in section 199 of the Adi Parva as the butcher-priest in a yajna of the gods, because of which humans do not die. Only in section 9 is Dharma called the god of death who resurrects Ruru’s snake-bitten wife Pramadvara, raising the speculation that he got identified with Yama.

Devy misses the backdrop of the divine plan (as in the Trojan War) to rescue earth from proliferating demonic rulers. Gods take human birth to engineer a massively destructive war whereafter they merge into their original selves. There is no cycle of rebirth here, which distinguishes the MB from religious texts.The MB articulates the concept of four “yugas” (like the Hellenistic four ages) of which Vyasa calls Kali the best when bhakti fetches swift salvation, without the intensive ascesis and elaborate sacrificial rituals of earlier eras. Devy proposes that the MB war keeps the kala-chakra, wheel of time, in perpetual motion. It is not a war to preserve ritualistic dharma. Balarama’s strange aloofness from the fratricide at Kurukshetra and Prabhasa, despite being the avatar of Shesha and a white hair of Vishnu’s, goes unnoticed.

With the expanse and depth of Devy’s reading, not mentioning Sukthankar’s profound insights in On the Meaning of the Mahabharata is strange. Further, as Devy pinpoints Yudhishthira and Yama as the composition’s main focus, the omission of Buddhadeb Bose’s masterly portrayal of Yudhishthira as the true hero in The Book of Yudhishthira is puzzling.

Devy concludes that the MB “unites us as a nation through a similarly perceived past, not through a similarly perceived collective self…not in any imagined territorial national space…(but) in Time…the never-stopping kala chakra…a great spirit of acceptance of all that is.” Vishnu’s couch, the infinite coils of Shesha, and Krishna’s discus, both symbolise Cosmic Time and its endless revolutions.

The appeal of the MB, however, is not limited to India. Even when shells and bombs were exploding in the streets during the siege of Leningrad in 1941, Vladimir Kalyanov was translating the MB into Russian in the Academy of Sciences on the Neva River embankment by the dim light of wick lamps, with no light, no fuel and no bread in the city. Nehru admired that nothing interrupted the work even during the hardest of times.

[This was published in a slightly altered form in The Book Review issue of October 2023, pages 21 to 23

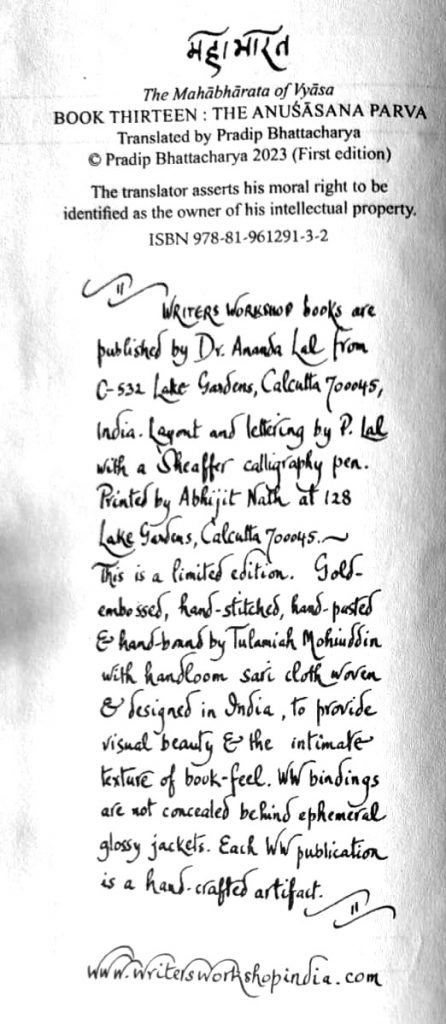

The Anushasana Parva: The Book of Instructions

This is Book 13 of the Mahabharata, and the most complete English translation, in verse and in prose carefully following the original, published on 5th October 2023 by Dr. Ananda Lal from www.writersworkshopindia.com

The project that Prof. P. Lal began in 1968 and was unable to complete (he could publish only 16 of the 18 books before passing away) is now complete. My translation of the complete Mokshadharma Parva came out in 2016.

My guru-dakshina to my Acharya is complete.

APPROACHING THE ADI-KAVI

APPROACHING ADI-KAVI VALMIKI[i]

Pradip Bhattacharya

The Department of Comparative Literature of Jadavpur University founded by the litterateur Buddhadeb Bose in 1956 was the first such in India. It has now embarked upon an ambitious project: a series of research publications in four categories, viz. Texts, Contexts, Methods; Indian and Asian Contexts; Literature and Other Knowledge Systems; and Lecture Series. The overpriced slim volume under review belongs to the last category. From the editors’ Introduction it seems that Goldman did not deliver this lecture but sent it as a written contribution. This is a pity, because documented interaction with an audience would have made it a far more significant publication. This extremely well-written “lecture” is not much more than an introduction for beginners, albeit a very competent one, to Valmiki’s work and hardly falls under the rubric of “research”.

The Ramayana (R) presents specific hurdles before the modern reader: it depicts a civilization of circa the first millennium BCE far removed from us; its language is ancient Sanskrit, which is not easily accessible. Further, Sanskrit did not have a principal script universally used. The R has spawned widely varying versions in almost all languages and different scripts of South and Southeast Asia “from Afghanistan to Bali” and is depicted in varied media. Surprisingly, Goldman makes no reference to the Belgian priest Camille Bulcke’s encyclopaedic Hindi study of these variations.[ii]

Adopting the linguist Kenneth Pike’s terms emic (subjective) and etic (objective), Goldman identifies two types of group-approaches to the R. In the former, fall variations in Indian languages and media. The latter is consists of scholarly studies in various disciplines world-wide, including translations in non-Indian languages.

Goldman asserts that the presumption of a single divinely inspired composer disseminating his composition through twin rhapsodes who recited it in toto before the public is a myth. The text would have undergone changes on the lips of differing bards and redacteurs owing to lapses in memory and improvisations responding to the changing audience and place. We can witness this phenomenon today in the “Pandavani” folk retellings of the Mahabharata (M) in Central India. Those Ramayana rhapsodes were given the collective name, “Valmiki”. Thus, like many Western Mahabharata scholars who dismiss Vyasa as a myth, Goldman denies the existence of Valmiki.

Further, he denies the possibility of so bulky a work being transmitted orally from Afghanistan to Bali without being reduced to writing, as evinced by innumerable manuscripts in circulation through South and Southeast Asia from about the end of the first millennium CE. Errors and changes occurred while copying a manuscript into different scripts. Thus, between the Northern and the Southern Indian script recensions only about one third are identical. Moreover, within each recension there are regional variations depending on the script in which the copies have been made.

A very important clarification Goldman provides is that the Baroda critical edition of “India’s National Epic” does not represent the original, but seeks to present an archetype constructed out of the best manuscripts that would be nearest to the period of the oldest available manuscripts. The abundance of textual variants poses a major problem in trying to assess the poem’s original form. Goldman hazards a guess that the R was produced around 500-100 BCE, while its oldest manuscripts go back only to the 12th or 13th centuries CE. So we have over 1700 years of no written record of the R. Therefore, “the etic reconstruction of the Ramayana’s genetic history is naturally going to be at odds with its emic receptive history of the work.” While to scholars it is a bardic poem orally performed and transmitted, to its audience it is the work of a single composer, the first poet (adi–kavi), who was a contemporary of Rama in mythical times. An avatar of Vishnu, he descended on earth to destroy demonic oppressors of sages and establish a golden age lasting millennia. Thus, according to the emic view, “it is a chapter of divine history rendered in a new form, that of poetry.” Raising the stimulating question, is the R “a poetic history or a historical poem”, Goldman leaves it hanging in the air. It would have been very interesting to study the reactions of the audience, had this been a live lecture.

Looking into the nature of the R vis-à-vis the M, Goldman notes that the former is far more poetic and emotional than the latter. The predominant emotion of the R is “karuna rasa”, pathos, whereas for the M a new emotion was added by the critic Anandavardhana (c. 9th century CE), “shanta rasa”, worldly-detachment or serenity. Earlier, the poet Bhavabhuti (c. 8th century CE), had asserted that “karuna” is the only rasa. However, in his last work Alf Hiltebeitel has argued very persuasively that the M’s rasa is “adbhuta-wonder”. Where the R holds up a mirror for rulers and families, the M portrays the incredibly complex ramifications of dharma in society and the individual.

Besides ignoring the story of Rama recounted in the M, Goldman has not noticed another structural similarity between the two mahakavyas that young Ramayana aficionado Saikat Mandal has pointed out. The Tilaka commentary on R by Nagoji Bhatta or Ramavarma (1730-1810) glosses the Uttarakanda as the “khila” (supplement) of the R just as the Harivamsha is of the M. The significance of this needs exploration.

Goldman expatiates at length on how the R records the inception of Valmiki’s composition, which is “a later addition to the fully developed work” for establishing it as the divinely inspired first poem. Its list of seven of the eight “rasas” shows it to be later than Bharata’s treatise, Natyashastra. Goldman goes on to show how the R differs from the Homeric epics in characteristics such as rapidity, being plain and direct in syntax, language and thought. He finds Valmiki hyperbolic, using rhetorical figuration aplenty, highly formulaic and repetitive, unlike Homer’s directness. The literary quality of the R is complicated, being a poem to delight while also being a chronicle. Goldman could have noted how, in all these features, the R is similar to the M and also different, as discussed at length by Sri Aurobindo in “Vyasa and Valmiki”.

Further, the R has grammatical forms that violate Panini’s rules and could be seen as poetic flaws. Its first and seventh books are of a later date, in less refined language. Goldman quotes at length from Homer and Valmiki to exemplify his arguments and to show how adept the latter is in portraying beauty in persons and in nature, including the frightful. Pursuing Abhinavagupta’s view of rasadhvani, Goldman analyses how the raw emotion of grief is sublimated by Valmiki to make karuna rasa the major aesthetic flavour of poetic composition, transmuting shoka (grief) to shloka (verse). The climax is reached in ending with Sita’s descent into the depths of the earth, leaving Rama desolate.

[i] Robert P. Goldman: Reading with the Rsi—a cross-cultural and comparative literary approach to Valmiki’s Ramayana. Orient BlackSwan, Hyderabad, 2023, pp. xvii+54, Rs.385/-

[ii] English translation The Rama Story by Pradip Bhattacharya published in 2022 by the Sahitya Akademi.