Alf Hiltebeitel: Freud’s Mahabharata. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. xxiii+298, Rs. 650.

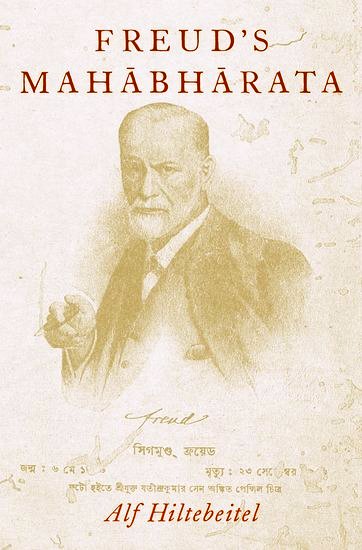

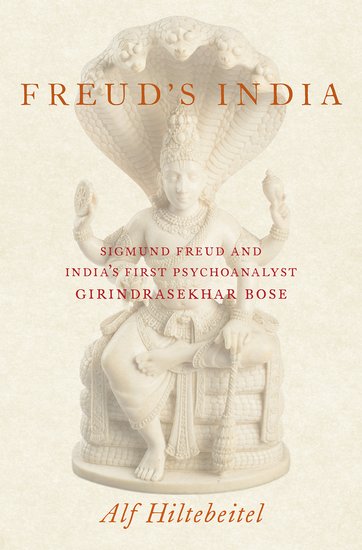

The cover of Hiltebeitel’s “Freud’s Mahabharata” has an interesting personal involvement on my part. Alf had emailed me in desperation having failed to trace this sketch drawn from a portrait of Freud (sent by Freud to Bose in 1926) by a Bengali artist Jatindra Kumar Sen commissioned by Dr. Girindrashekhar Bose which he used as the cover of the first edition of his Bengali work, “Swapna” (1928). With some difficulty Smt. Sunita Arora of the National Library (who had been put on the job by my young colleague Shri Raghavendra Singh IAS, its Director) traced it to a very fragile copy, repaired their high-resolution camera for taking a good photograph and sent that to me which I emailed Alf. That is how a Bengali artist’s sketch ended up on a work published abroad and in India. Bose removed the sketch from subsequent editions of “Swapna” possibly because he fell out with Freud around 1931. Dr Bose had sent Freud an icon of Vishnu seated on Ananta which Freud kept on his desk. This features as the cover of Hiltebeitel’s “Freud’s India”.

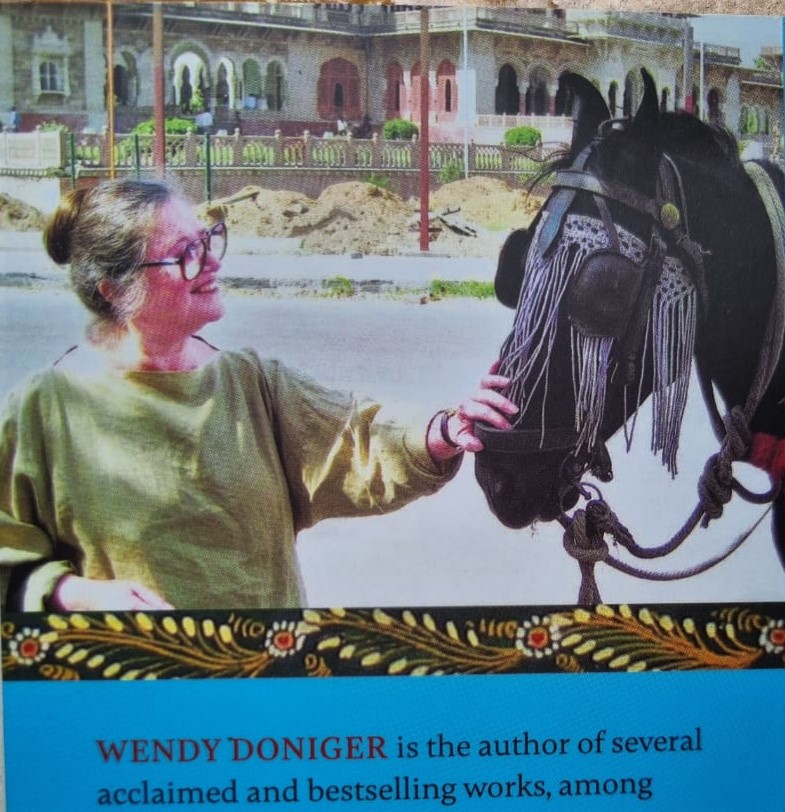

Hiltebeitel’s new work follows up on his “Freud’s India” where he explored personal experiences following his father’s death and his divorce that recalled Freud’s life. The cover of the book has an interesting story. Hiltebeitel had emailed me for help having failed to trace this sketch drawn from a portrait of Freud by a Bengali artist, Jatindra Kumar Sen commissioned by Dr. Girindrashekhar Bose, founder of the Indian Psychoanalytic Society, from a portrait Freud had sent him in 1926. Bose used it as the cover of the first edition of his Bengali work, “Swapna” (1928). With some difficulty Smt. Sunita Arora of the National Library (who had been put on the job by its Director, my young colleague Shri Raghavendra Singh IAS) traced it to a very fragile copy, repaired their high-resolution camera and sent me a photograph which I emailed Hiltebeitel. Bose had sent Freud an icon of Vishnu seated on the serpent Ananta, which Freud kept on his desk. This features as the cover of Hiltebeitel’s book, “Freud’s India”. Bose removed the sketch of Freud from subsequent editions of “Swapna” possibly because he fell out with Freud around 1931. Freud had referred to Bose in 1922 as an extraordinary professor who had founded a local psychoanalytic group in Calcutta.

The book immediately stimulates interest by its intriguing title since Freud never mentions the Mahabharata (MB). Dipping into it we find that it is in three parts of which the middle portion consists of chapters 2 through 5. Chapters one and six are the first and third parts. Beginning with Freud’s essay, “Das Unheimliche” (The Uncanny, as translated by James Strachey), Hiltebeitel links the MB by arguing that its dominant flavor (“rasa”) is the uncanny, as Sheldon Pollock translates “adbhuta”, and not the heroic (“vira”). He interprets the story of the five Indras immured in a cave as a pre-Oedipal intra-uterine fantasy of being buried alive, which Freud called “the most uncanny thing of all”. Hiltebeitel misses out Edgar Allan Poe’s terrifying take on this in “Tomb of Ligeia”.

In an elaborate examination of the myth of Aravan/Iravat/Kuttantavar, Hiltebeitel links his overhearing in the womb about Krishna’s wish to kill him and then emerging feet first to kick Krishna into the ocean with Freud’s theory about the return to the womb in sleep. Hiltebeitel sees in this ocean a reflection of “the oceanic feeling” that Romain Rolland wrote to Freud about, troubling him no end. There are analogous stories about Ahiravana in the Bengali Ramayana of Krittibas and Vivek in the Bengali Mahabharata of Kavi Sanjay which would have added grist to Hiltebeitel’s mill.

Influenced by Freud’s “Moses and Monotheism”, Hiltebeitel theorizes that the MB’s core myth of the divine plan to unburden the Earth reflects the trauma experienced by rural Vedic Brahmin communities of foreign invasions and the impact of “India’s second urbanization” after 500 BCE in the Gangetic plain, the first having been the Harappan civilization. This is the “urban unconscious” of Brahmanism, like Freud’s Judaism. Interestingly, the demons-on-earth (Jarasandha, Kamsa etc.) occupy the chief cities (Rajagriha, Mathura etc.). Hence, the extolling of forest-living gleaners.

It is surprising to find Hiltebeitel supporting the long discredited theory, revived by F. Wulff Alonso, of Indian epics drawing upon the Greek mythic corpus for their matter of the divine plan to relieve Earth’s burden. He does admit, however, that the MB’s myth is apocalyptic unlike the Homeric. This myth that is practically the frame story is repeated five times. First by Vaishampayana in his genealogical account, next twice by Vyasa narrating the five Indras myth and while consoling Dhritarashtra after the war, the fourth time by Narada during the rajasuya yajna and finally at the end by Vaishampayana.

Hiltebeitel finds a parallel to Freud’s “phylogenetic myth-making” with the MB’s combining myths of genealogy, cosmology, sacrifice and war in the ontogenesis of its divine plan. Freud’s assertion that the primal patriarch drove his sons out when they came of age, virtually castrating them, whereafter they could remain in the horde as harmless labourers (a stage corresponding to dementia praecox), is paralleled in the MB’s myth of Yayati disinheriting and banishing all but one of his sons. Hiltebeitel even suggests that at 23 volumes Freud’s work is larger than the MB, both texts looking to forge a new consciousness of a civilization, both heterogenous in relating myth to narrative, stylistically varied , dialogical, propounding a heroic persona with a prominent role for women.

Hiltebeitel juxtaposes the MB’s three tales about dead mothers (Madri, the Nishada woman, the corpse supposedly of their 180 year old mother strung up on a tree by the Pandavas) with Freud’s three texts dealing with the dead mother complex. Kunti is seen in the role of a dead mother to Yudhishthira, staying aloof from him and finally abandoning her sons, just as Gandhari never looks upon her children and finds Duryodhana rejecting her in open court. Hiltebeitel posits that it is Satyavati or even her fishy mother Adrika (Acchoda in the Harivamsha) to whom the Pandavas refer, as the corpse of their 180 year old “mother”, its stink being linked to her fishy birth. The dead mothers stack up over five generations (5 x 36 years per generation = 180) beginning with Satyavati (from the Yamuna) and Ganga, ending with Draupadi’s ultimate sonlessness. Satyavati is known by her fishy odour inherited by Vyasa. She is dark like the river Yamuna across which she plies a ferry, as contrasted with the pellucid celestial river, the Ganga. That she is originally called “Kali” is very significant. In iconography, Vishnu’s two wives are the Earth goddess and Shri-Lakshmi, both of whom are at the core of the MB’s divine plan.

Hiltebeitel devotes considerable space to examining how Freud’s interests are paralleled by the knowledge about Indian goddesses of Dr. Girindrashekhar Bose (who sent Freud an icon of Vishnu and had his portrait sketched which forms the cover of this book). Differing from Freud, Bose said that in India the wish for castration occurs early in childhood when, identifying with the mother, he wishes to be female. Dread of castration comes later in the Oedipal identification with the father. Hiltebeitel posits that Kali fits the profile of Bose’s “Oedipus mother”. Issues of castration come up in the cult of Aravan/Kuttantavar who sacrifices himself to Kali before the MB war.

Bose theorized that the wish to be hit always accompanies a wish to hit. In “Freud’s India” Hiltebeitel had wondered whether this wish to be struck characterizes snakes. Aravan’s mother is the female serpent Ulupi. Snakes who “infest the MB”, argues Hiltebeitel, largely represent not tribals but the unconscious, “basic raw wishes, hostilities, or desires” of the unconscious. Analysing three versions of the Aravan/Iravat/Kuttantavar tale, Hiltebeitel finally admits that his self-sacrifice before the war (“kalappali”) cannot be said to involve a wish to be struck. However, this Tamil cult, much celebrated by Hijras, has evidence of a link between the castration wish and a desire to be female that Bose posited as occurring in the pre-Oedipal stage. In this phase the “Oedipus mother” has a powerful role, as seen in Aravan’s multiple mother figures (Ulupi, Draupadi, Kali). Hiltebeitel concludes that Bose’s theory explains these Indian cults which Freud’s does not.

Examining Freud’s work on Moses and on Jokes, Hiltebeitel links the discussion to the tales of gleaners in MB, claiming that the epic was the composition of “a committee of ‘out of sorts Brahmins’” (hence the extolling of gleaners) in the 2nd century BCE in Kurukshetra. Vyasa’s stink and disagreeable appearance makes him “the consummate out-of-sorts Brahmin.” This period of second urbanization (600-300 BCE) saw the rise of towns vis-à-vis forest life. Gleaners in the Naimisheya grove near Kurukshetra complete a twelve-year yajna during which, because of the numerous rishis, the tirthas got urbanized (“tirthani nagarayante”). Hiltebeitel imagines them traumatized by foreign invasions (hence the prominence of the north-west in MB) and the challenge of heterodox movements backed by royal patronage (Chandragupta and Jainism, Bimbisara and Ajivikas, Ashoka and Buddhism). He argues that they “projected features of current second-or first-century urban architecture back into” the Vedic world whose memories lay in their subconscious. They developed the Rig Veda’s ten mandalas (16th to 11th century BCE) into the ritualistic three other Vedas (11th to 9th century BCE) and then their branches (8th to 3rd century BCE) climaxing in the encyclopaedic MB in the fourth stage in the 2nd century BCE. The references in MB to Greeks, Chinese and Shakas, but not the Pahlavas or Kushanas, indicates a completion of composition before the end of the pre-Common Era, by the late Shunga or Kanva times. Support is found in the MB’s reference to the land being dotted with “edukas” (Buddhist mounds of relics). In the Book of the Forest, one Shaunaka discourses to the Pandavas on the Buddhist eight-fold path; a butcher speaks the Jain version of ahimsa and in the Shanti Parva Bali lays out the Jain doctrine of six “leshyas” (colours) of matter.

Seeking to find correspondences in MB with Freud’s theory about jokes, Hiltebeitel makes a laboured argument that Vyasa’s levirate episode with Ambika and Ambalika contains an innuendo: the two “mahishis” (chief queens/female buffaloes) unite with the smelly, unkempt Vyasa in the role of the horse of the ashvamedha rite. In the “Narayaniya” narrative Vyasa reveals that he is born of Harimedhas, the essence of the Horse-headed avatar. The year-long vow Vyasa wanted them to observe parallels the horse-sacrifice’s prescription of abstinence for a year. By rejecting this, Satyavati renders the queens impure for the rite. Hiltebeitel hazards a bad joke of his own: “Vyasa’s shaggy-dog story has turned out to be a shaggy-horse or a talking-horse story.”

A very rewarding read is Hiltebeitel’s analysis of the narrative structure of the “Narayaniya” identifying how the dialogue level shifts thrice from the inner frame (Janamejaya querying Vaishampayana, within which Vyasa speaks to the former too across six generations) to the outermost (Vyasa discoursing to his five pupils) through the outer frame (Rishi Shaunaka querying Ugrashravas Sauti) via the intermediate dialogues (Yudhishthira querying Bhishma). Ultimately, Hiltebeitel sees the MB as “the recovered memory” of a Vedic past replete with “partially unconscious and forgotten meanings about that past”. —Pradip Bhattacharya