By Prof. Indrajit Bandyopadhyay, Department of English, Kalyani Mahavidyalaya, W.B.

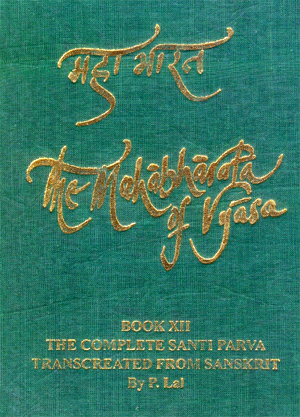

Bhattacharya completes the academic and literary journey embarked upon by Padma Shri Professor Purushottam Lal’s first ever attempt at an English verse “transcreation” of the Mahābhāratain 1968, completing sixteen and a half of the epic’s eighteen books. Following his untimely demise in 2010, Bhattacharya took up the unfinished job of his guru, and translated the Mokṣadharmaparvan of the Śānti-parvan in 2018. His “guru–dakṣiṇā”, as he calls it, is complete with the translation of the Anuśāsanaparvan in 2023.

Bhattacharya humbly acknowledges of “not being a poet like Prof. Lal”, and has “striven to follow the spirit of the Lal transcreation”. He proposes to “keeping to the original syntax as far as possible without making the reading too awkward” realizing “the immensity of what the Professor achieved” and the “Meru-high task”.

Indeed it is no exaggeration, considering the cultural sensitiveness inherent to the massive project. The Śāntiparvan and Anuśāsanaparvan are the twin cruxes of the Mahābhāratan philosophy encapsulating ancient Indian wisdom, thoughts, insights and discourses on various aspects of Dharma: Mokṣadharma, Rājadharma, Strīdharma, Dānadharma, as also the practical and pragmatic applications of dharma in daily life. In short, the Śāntiparvan and the Anuśāsanaparvan are the compendium of Dharmaśāstra and Arthaśāstra. With the well accepted dating of the writtenMahābhārata as commencing in the 4th century BCE marking the transition from the oral text, they may be taken as complementing and corresponding to the Kalpasūtra tradition of Dharmasūtras (600-100 BCE; P. V. Kane’s dating) and Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra of the age (3rd century BCE).

In the Anuśāsanaparvan, various aspects of dharma have been demonstrated through puraṇik narratives, parables and fables, which further highlight the correspondence with Viṣṇu Śarma’s Pañcatantra (200 BCE) and Buddhist Jātaka narratives (circa 3rd century BCE). The parvan has unique tales like that of King Bhaṅgāśvana (13.12) who undergoes a mysterious sex-gender transformation and then prefers to remain a woman because –

“Women in uniting with men have

greater pleasure always.

For that reason, Śakra-Indra, womanhood

I choose indeed.” (Bhattacharya: XIII.12.76)

In all probability, the original Śāntiparvan was later split to structure the Anuśāsanaparvan as a separate entity. The Spitzer manuscript belonging to the Kuṣāṇa period, and Carbon-14 dated as 80-230 CE, does not mention the Anuśāsanaparvan. Nor does Al-Biruni (973-1050 CE) in his ‘India’, while mentioning that the Śāntiparvan consists of 24000 ślokas. However, Abul Fazal (1551-1602 CE) in his preface to the Razmnama mentions the Śāntiparvan of 14732 ślokas and the Anuśāsanaparvan of 8000 ślokas. This proves beyond doubt that the integrated Śāntiparvan was restructured and split into the present Śāntiparvan and Anuśāsanaparvan somewhere between the 11th and 16th century CE.

It is for that reason, coupled with the fact that Ugraśravā Sauti imagines the Śāntiparvan as the bṛhatphalaḥ (1.1.62d@1_52) or the great fruit of the Bhārata-vṛkṣa (the ‘Mahābhārata-tree’), a glory shared by the Anuśāsanaparvan being originally the fruit, Bhattacharya’s English translation in easy flowing language gains immense cultural significance. Sauti’s “hundred parvan” count regards the Anuśāsanaparvan as the ānuśāsanikaṃ param (1.2.65a) and in the parvan-summary he mentions the parvan as ānuśāsanam uttamam (1.2.201a; 204a).

The academic and cultural importance of Bhattacharya’s translation, “the first English translation of the Anuśāsanaparvan in free verse (alternate lines of ten and four-to-six feet) and in prose (as in the original)”, rendering the difficult Mahābhārata-ślokas (“cryptic and complicated – true Vyāsa-kūṭas”) accessible to the general public with opportunity of comparative study with other English translations from Kisari Mohan Ganguli to Bibek Debroy, through M. N. Dutt and Van Buitenen, must be ascertained and critically understood in this light.

Bhattacharya experiments with translating Sanskrit into English, as much with English language itself. Bhārata-India being an independent raṣṭra, the colonial hangover must be over. In any case, Sanskrit has no obligation to fit into the English mould. Besides, English is no more an alien language. Therefore, English must now be Indianized by active agency.

Bhattacharya’s translation experimentation pioneers that cultural consciousness. He retains Sanskrit words that are in the Oxford English Dictionary, and following Prof. Lal’s style of rendering some Sanskrit words and giving their contextual English synonym with a hyphen, also coins Sanskrit-English compounds or retains the Sanskrit word as it is. In the latter case, initially, the unused eye and ear may miss the rhythm; however, the Sanskrit-English compound has a rhythm of its own, adds to poetic flavour, enables Bhattacharya to maintain syllable counts in feet, and also enables him to be simultaneously translator and reader.

Those preferring the rational approach to the Mahābhārata pioneered by Baṃkim Candra Chattopādhyāya in ‘Kṛṣṇacaritra’ (1886) may detect in this parvan several clues to the poetic and rational explanation to why Vyāsa (and “Vyāsaīds” – to use Sukthankar’s coinage) hail Yudhiṣṭhira as the Dharma-Indra king on earth, poetically and mythically represented as Deva Dharma’s biological son and an ex-Indra incarnate. For example, there is an episode in which Yudhiṣṭhira, the “new Indra on earth” meets none other than the devaguru Bṛhaspati to receive essential advice (13.112-114).

This is in all fitness of things. Yudhiṣṭhira is hailed as Ajātaśatru (e.g. 1.133.25c), as Indra is known in the Rigveda (Rv 5.34.1a; 8.93.15c).

In continuation of the Śāntiparvan–Mokṣadharmaparvan liberal philosophic and soteriological discourses and advocacy of liberal varṇa system (portraying non-brāhmiṇ characters like Sulabhā, prostitute Piṅgalā and śūdras as qualified for higher merit and social status through wisdom), the Anuśāsanaparvan advocates “Secular Humanism” significantly mouthed by Maheśvara Śiva in presence of Umā. We recall: Umā teaches Indra about Brahma (Kena Upaniṣad, 4.1).

Bhattacharya, in a rediscovery of his translation style of the Mokṣadharmaparvan, retains the unique experimentations with the translation genre. He departs from customary translations in providing the original Sanskrit śloka in cases of key messages of the Mahābhārata.

For example, Bhattacharya retains Maheśvara’s words to Umā: sarvabhūtānukampī yaḥ sarvabhūtārjavavrataḥ / sarvabhūtātmabhūtaś ca sa vai dharmeṇa yujyate // (CE 13.130.28) and then gives the translation (Bhattacharya XIII.150.39-40; p 917-918).

Similarly, he retains the next śloka: ārjavaṃ dharma ity āhur adharmo jihma ucyate / ārjaveneha saṃyukto naro dharmeṇa yujyate // (13.130.30)

And translates:

“Sincerity is dharma, it is said:

Adharma is crookedness called.

United with sincerity here,

A person is yoked to dharma.”

One central message of the Mahābhārata is the Śiva and Nārāyaṇa oneness (stated unequivocally in the Śāntiparvan, e.g. 12.330.64), or to put it in the historical context, Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava synthesis.

Here, Śiva’s placing ārjava as equal to and even greater than the Vedas is not only consistent with Vyāsa and Kṛṣṇa’s reformative and dynamic approach to the Vedas (for example, Gītā.2.42 / Mbh. CE 6.24.42), but also brings Jainism and Buddhism within the fold of Dharma and cultural synthesis as part of the great humanistic and synthetic attempt of the Mahābhārata, ārjava (ajjava, ajjavayā, and ajjaviya in Pāli) being one of the key doctrines in both Gautama Buddha and Mahāvīra’s teachings.

In Jainism, ārjava refers to one of the ten-fold dharma (i.e., yatidharma) capable of leading across saṃsāra, according to chapter 3.3 [sumatinātha-caritra] of Hemacandra’s 11th century Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra.

One would have missed these dhārmika-saṃskṛtika links had Bhattacharya rendered ārjava as “sincerity” only without giving the original word. Needless to emphasize, the English word “sincerity” falls short of the dhārmika and cultural significance of ārjava.

Another important śloka in Maheśvara’s mouth deconstructing rigid varṇa system is: na yonir nāpi saṃskāro na śrutaṃ na ca saṃnatiḥ / kāraṇāni dvijatvasya vṛttam eva tu kāraṇam // (13.131.49)

Bhattacharya retains the śloka and translates:

“Neither birth, nor sacraments, nor scriptures, nor humility

Are reasons for twice-born-hood. Conduct indeed is the reason”.

The retention of the original śloka gives the reader better opportunity to see the similarity with Gautama Buddha’s teachings in the Tripiṭaka.

Bhattacharya dedicates the Anuśāsanaparvan translation to the late Alf Hiltebeitel whom he regards “most prolific of Mahābhārata scholars”. This needs special mention because in many ways Prof. Lal and Bhattacharya’s approach to the Mahābhārata has been diametrically opposite to Hiltebeitel’s. While Hiltebeitel was one of the staunchest defenders of the BORI Critical Edition, the guru (Lal) and the “chelā extraordinaire” prefer the “full ‘ragbag’ version” reminding us of the Nīlakaṅṭha tradition, which is, in Sukthankar’s words: “smooth and eclectic”, “of an inclusive rather than exclusive type”. (Prolegomena, LXVI)

To conclude: Bhattacharya’s translation is definitely uttamam true to the laudatory perspective of the Anuśāsanaparvan.

Published in “Indian Literature”, Sahitya Akademi’s Bimonthly Journal, Jan-Feb 2025.