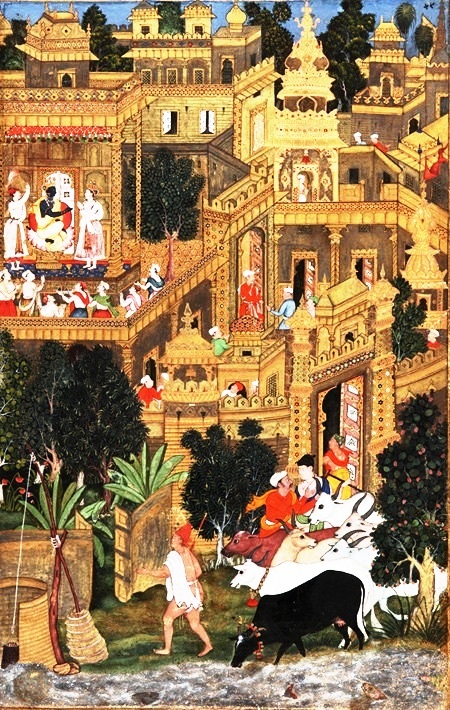

Dvaraka c. 1585 from the Razmnama

In Parvasamgraha (I.2.378), the Mahabharata (MB)’s list of contents, Harivamsha (HV) is called its khila of 12000 slokas, consisting of two parts:-

“The Harivamsha and Bhavishya sections form the epilogue.

In the Harivamsha the maha-rishi composed twelve thousand slokas.”[1]

Young Ramayana aficionado Saikat Mandal has noticed that there is a similarity here with Valmiki’s mahakavya. The Tilaka commentary on the Ramayana writes about the final “kanda”, “Uttarakanda” annotating I.2.43:

“The Uttarakanda is its khila as Harivamsha is to Bhaarata”.

Khila does not mean “appendix” i.e. superfluous, hence discardable, as most Western scholars render it. Rather, it is a complement or supplement essential for realising the significance of the main work, as we shall see.

Although Razmnama, the Persian translation of MB commissioned by Akbar supposedly includes HV, this portion has never been studied to verify its contents vis-a-vis the Sanskrit original, which would have helped determine the state of the text in the 1590s. However, when Kaliprasanna Singha produced the first translation of MB in Bengali (1858-66), he omitted this supplement, commenting that its language was distinctly later. The first English translation by K.M. Ganguli (1883-96) also did not include it. V.S. Sukthankar did not propose to include HV in the Critical Edition (CE) of MB, but later it was edited by P.L. Vaidya and published by the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) in 1969. The Chicago University MB translation project omits HV although the earliest known list of its parvas (the Spitzer manuscript c. 130-200 CE) includes the khilas. Since Ashvaghosha quotes some verses from the MB that are found only in HV, the text—at least the Harivamsha Parva—is dated to c. 1st century CE. Andre Couture in his Krishna in the Harivamsha (vol. 1)[2] places it in the Kushan era (1st to 3rd century CE).

Translations

A complete Malayalam translation in verse of HV was done by Kodungallur Kunhikkuttan Tampuran over a period of 3 years (1894-1897) and was published in 1906. Manmatha Nath Dutt was the first to translate HV into English prose (1897) which, unlike the vulgate in three books, contains two parts: Harivamsha Parva (incorporating Vishnu Parva) and Bhavishya Parva. This work, long out of print, contains many errors, such as locating Dvaraka “in the country of Kanyakubja or Kanouj” (chapter 35, fn.68). Only in 2008 was a sloka-by-sloka English translation by Dr. K.P.A. Menon IAS (Sanskritist and retired Defence Secretary of India) published by Nag Publications, New Delhi. It is not clear which text he used as there are numerous omissions and the CE is followed haphazardly. Editing and proofing are absent. It is riddled with gross typographical errors and textual hiatuses, the translator having passed away well before the publication. The Menon translation is unique for rhythmically rendering into English each half-verse of every sloka with the caesura in-between. One wishes this arrangement had been followed in other translations instead of resorting to pedestrian prose. Harindranath and Purushothaman’s translation of the vulgate is available online.[3]

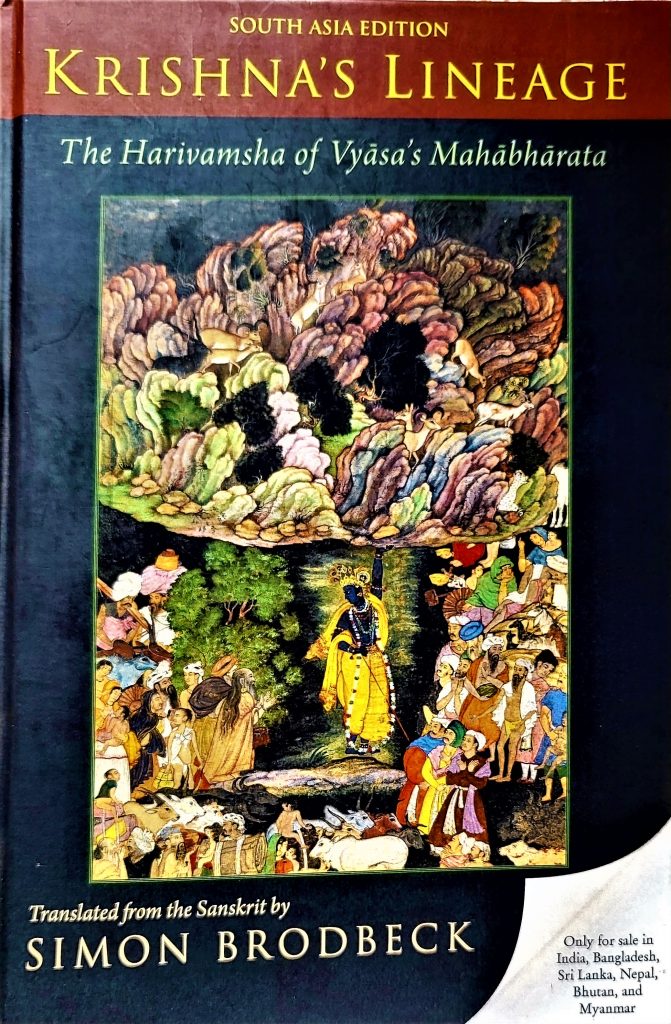

Simon Brodbeck translated the CE of HV in 2019[4] in prose with a brief Introduction and an elaborate genealogical appendix which is extremely helpful in clarifying relationships. His lengthy paper on the details of the translation, which would have served as an excellent Introduction, has been published separately.[5] Occasionally, Brodbeck successfully attempts a rendering in free verse, e.g. Section 30, verses 19-20 and 110.73:-

Fever flew through the air decked in wonderful gold,

but the lord of the world, in battle in bodily form,

used the bracelet on his arm to crush him in the heat of battle

and send him towards Yama’s domain.

While maintaining the division into three books, the CE is only a third the length of the vulgate (118 chapters containing 6073 slokas against 318 chapters and around 16,000 slokas). For instance, where the CE’s Bhavishya Parva is just 5 chapters, the vulgate runs to 135! Andre Couture,[6] A. Purushothaman and A. Harindranath[7] have strongly criticised the extensive excisions e.g. Jarasandha’s battle at Gomanta mountain with Krishna and Balarama, the elaborate account of the robbing of the Parijata tree, Pradyumna’s protracted battle with Shambara and his troops, how Dhanvantari came to propagate Ayurveda as king of Kashi in the second Dvapara Yuga and acquired godhood, which was denied him when he appeared at the churning of the ocean with the name Avja. It also omits the fascinating story of how Shiva by fraud got Raja Divodasa and his subjects to vacate Varanasi so that he and Parvati could live there away from the incessant bickering of his mother-in-law Mena. Later, Varanasi is said to have been depopulated by the rakshasa Kshemaka and re-established by Alarka by the grace of Lopamudra.

A very significant excision is Vishnu’s invocation of the goddess Arya Vindhyavasini although it occurs in all versions of the HV, except just three in Malayalam script, and is present in both the Sharada and Newari texts which Vaidya relies upon the most. This violates the very principles upon which the CE is based. The hymn is definitely pre-695 CE when it features in a Chinese translation of the Suvanabhassottama Sutra. This devi, under the names Nidra and Ekanamsha, plays a critical role in Krishna’s birth. Vishnu provides a lengthy description of the goddess of sleep to be born to Yashoda (47.39-45) and be named Kaushiki (her other name is Ekanamsha). She will be installed in the Vindhyas, decorated with peacock plumes, to destroy the demons Shumbha and Nishumbha, and be worshipped with pitchers of wine and flesh. Flying to the sky when smashed against a rock by Kamsa, like Durga she drinks and laughs loudly, foretelling that she will tear open his body and drink his blood. Kamsa’s verses in response (48.41) are memorable:

“It is Time that is people’s enemy; it is Time that rings the changes.

It is Time that carries away all. People like me are mere causal agents.”[8]

Vaidya, editor of the CE, finds the story of the Syamantaka gem peculiar and omits it. However, Andre Couture has shown that every element of it constitutes a carefully constructed narrative depicting the supreme sovereignty of Krishna. Indeed, he is the Yajna-Purusha, the lord of sacrifice (Agni and Soma), of the sun and the moon and through them of the two major royal lineages. It is as the Yajna-Purusha that he overcomes the three Vedic fires that confront him in the battle with Bana, an incident that makes no sense otherwise. Moreover, Yaska’s Nirukta refers to Syamantaka, proving its antiquity. Its appearance coincides with the founding of Dvaraka and it has a solar as well as an oceanic (i.e. lunar) origin. Krishna’s possession of it indicates his mastery of both these yajnic principles. Indeed, Janamejaya states that Vishnu contains both. Further, the Krishna-Jambavan duel inside a cave with Balarama posted outside is a clear parallel of the Vali-Mayavi duel with Sugriva standing guard in the Ramayana and should not be omitted.

Structure of the Text

HV begins with the rishi Shaunaka telling the wandering rhapsode Ugrasravas Sauti that he has forgotten to recount the history of the Vrishni and Andhaka clans. Despite Krishna being the key figure in MB, it is silent about his life before his first appearance in Draupadi’s bridegroom-choice ceremony and does not provide details about his lineage and family. Janamejaya, the befitting audience for narration of MB as the great grandson of Krishna’s sister Subhadra, justifiably asks Vaishampayana about his ancestral maternal uncle’s life and clan. At Janamejaya’s prompting, Vaishampayana also narrates the deeds of Krishna’s elder step-brother Sankarshana/Baladeva. Sauti states that having heard the HV, Janamejaya was freed of sins.

There is a distinct difference in the narrative structure between MB and HV. The outermost framework of Sauti narrating to Shaunaka and his followers is intact but, unlike in MB, Vyasa does not feature by way of bidding his disciple to recount it. There is also a change in the structure from chapter 101 to 104 where Vaishampayana quotes Arjuna who, at Bhishma’s behest from his bed of arrows, recounts Krishna’s greatness to Yudhishthira. In the tale of the rescue of a Brahmin’s sons the roles of Krishna and Arjuna are reversed: Arjuna becomes Krishna’s charioteer, driving through the northern sea-bed, the waters parting as with Moses leading the Exodus. At the end of this, Krishna proclaims to Arjuna that he is all creation and destruction, echoing the cosmic manifestation in the Gita. Thereafter, responding to Janamejaya’s request, Vaishampayana provides a brief list of Krishna’s deeds, viz. killing Vichakra, Naraka, Dantavaktra, Hayagriva, Kalayavana, robbing Indra of the Parijata tree, defeating Varuna, Bana, Shalva, Mainda, Dvivida and Jambavat, restoring to Sandipani his dead son, lifting the curse from Nriga, freeing kings imprisoned by Jarasandha, burning down Khandava, presenting Arjuna the Gandiva, consoling the exiled Pandavas, promising Kunti that he would protect them in the war, becoming their envoy too, and destroying all kings in his supernatural form. It is significant that Vishnu Parva is named Ashcharya Parva, the Book of Marvel, at 113.82 (p. 347). It reminds us of Hiltebeitel’s rhetorical query: does not the marvellous and the sense of wonder apply to the entire MB “better than heroism, or a peacefulness resigned to disillusionment?”[9] At the end his recital of the Vishnu Parva, Vaishampayana tells Janamejaya (113.81) that the rite has been completed, referring to the snake-sacrifice. The same completion is stated in the last book of MB. Thus, HV is, in Brodbeck’s words, “as it were a flashback, which here catches up with itself. The rite is simultaneously the rite of reciting the tale (fn. p. 347).” Vishnu Parva ends with the bard Suta telling sage Shaunaka that he has recounted the HV as Janamejaya had heard from Vaishampayana.

Significant Data

HV supplies some chronological data connecting with MB events. Omitting the popular tale of Satrajit obtaining the sun-like Syamantaka gem, the CE has his brother Prasena obtain it from the sea. Krishna visits Varanavata after the supposed death of the Pandavas and Kunti in the House-of-Lac conflagration. That is where Satyabhama rushes to complain that Shatadhanva has murdered her father Satrajit and stolen the gem. Krishna hastens to Dvaraka and with Balarama chases Shatadhanva. Balarama suspects Krishna of taking the gem after killing Shatadhanva near Mithila. Disgusted, he leaves Dvaraka for Mithila where Duryodhana arrives for training in mace-battle. Sixty years later Krishna succeeds in persuading Akrura (to whom Shatadhanva had given the gem) to give up the jewel in public. This timeline needs to be collated with the MB. Some geological data is also found in HV: Balarama dragged the Yamuna to make it flow through Vrindavana; Hastinapura leans towards the Ganga since he dragged its rampart with his plough when Duryodhana refused to release Krishna’s son Samba.

Harivamsha and Mahabharata

HV takes care not to repeat MB. It leaves out the Pandava-Dhartarashtra conflict, the massacre of the Yadavas and the submerging of Dvaraka. HV’s goal is to establish and propagate Krishna’s avatarhood, reaching its acme in portraying him in the battle with Banasura with eight arms and a thousand heads, complemented by Balarama with a thousand bodies. That is a battle unique of Shiva and Skanda fighting Krishna, Balarama and Pradyumna which makes for fascinating reading (chapter 112). Here the CE is very erratic in excising verses about the goddess Kotavi who manifests to block Krishna from Skanda at 112.49, following which there is an abrupt hiatus. Then, as if this has not occurred, at 112.97 she stands naked between Krishna and Bana. The vulgate makes far better sense: she appears naked to protect Skanda, whereupon Krishna indignantly shoos her away and she vanishes with Skanda. Later, Shiva and Uma send her again to protect Bana from Krishna’s discus. Krishna shuts his eyes so as not to gaze upon her nudity and severs Bana’s thousand arms. Bleeding from his severed thousand arms, Bana dances for Shiva who makes him immortal, whole and grants him his desired name “Mahakala” (Great-Ender) among the pramatha hordes. Shiva also grants that devotees who dance thus, dripping blood, will be blessed with sons. That might be the origin-myth of the folk festival of “charak” towards the end of the the month of Chaitra in which devotees whirl around a pole suspended by hooks through their backs and pierce their tongues etc.

In Krishna’s confrontation with the mountain fires, since Brodbeck retains their original names, it would have been only appropriate to retain ahavaniya too instead of rendering it only as “offertorial” (110.16) which primarily refers to the Eucharist—an incongruous association here. Shiva does not say, “if I get close to gangs of tormentor fiends my mind gets unsettled,” as translated. The pramathas (tormentor demons) being his constant companions, he says, “I will stay with the pramathas; I do not wish to fight,” (112.84).

The killings of Jarasandha and Shalva do not feature, having already been told in MB. The reason why in MB Krishna insists on Jarasandha being killed is explained in HV, viz. his relentless attacks on Krishna and Balarama. Raja Ekalavya is said to live on mount Raivata near Dvaraka. However, no details are given of how Ekalavya was killed, which in MB Krishna claims he did. In MB Arjuna, while escorting the Ashvamedha horse, kills Ekalavya’s son. HV mentions the intriguing fact that Naraka is born of the Earth Goddess by the Varaha (boar) avatar. Its implications need to be teased out. The commentator Nilakantha comments that Krishna took Satyabhama along with him to fight Naraka because he could be slain only with her consent, she being a portion of the Earth Goddess. The Southern Recension of HV contains a detailed account of Satyabhama battling Naraka when Krishna is knocked down,[10] which the CE omits simply because the editor, P.L. Vaidya, felt that women in Puranic literature do not fight! The Kalika Purana mentions Naraka being so named as the baby was found resting with its head on a human skull.

There is also the theme of an earlier avatar (Parashurama) being worsted by a later one (Rama). Further, just as Arjuna Kartavirya, disciple of an earlier avatar Dattatreya, is killed by the later avatar Parashurama, so the deaths of Parashurama’s disciples (Bhishma, Drona, Karna and Rukmi), are brought about by the new avatars Krishna and Balarama. Parashurama’s severing of Arjuna Kartavirya’s thousand arms is replicated by Krishna with the demon Bana. Actually, during this duel Krishna specifically refers to that incident.

The vulgate contains fascinating descriptions of the Yadavas’ sports in the sea and elsewhere and the delectable food they enjoy in picnics. Jaimini’s Ashvamedhaparva has similar lists of food-items. HV contains the tale of Bhanumati’s ever-renewable virginity and fragrant body from Durvasa’s boon which recall Satyavati and Kunti. She is married to Sahadeva, but there is no mention of progeny. Here, after the internecine massacre with reeds that devastated the Vrishnis, Gada, Pradyumna and Samba resettle in Vajrapura on the northern flank of Mount Meru, which was the kingdom of the demon Vajranabha whom Pradyumna killed after marrying his daughter Prabhavati secretly. In MB, however, none of them survive the massacre at Prabhasa. MB merely mentions that the son of Yuyudhana (Satyaki) was settled by Arjuna on the banks of the Sarasvati with old Yadava men, women and children. HV names him as “Asanga” whose son was Bhumi and Bhumi’s son was Yugandhara. MB also states that Arjuna settled Kritavarma’s son with the Bhoja women in Marttikavata (on river Parnasa in Rajasthan).

The first book of HV is very much of a Purana narrating the creation of the cosmos, the great war between gods and demons and the solar and lunar lineages. The second book, Vishnu Parva, is devoted to Krishna deeds other than those in MB: killing Putana, uprooting twin Arjuna trees, moving from Vraja to Vrindavana, taming Kaliya, killing Dhenuka, lifting Govardhana, killing Arishta, Keshin, Kuvalayapida, Chanura, Kamsa, resurrecting Sandipani’s son and a Brahmin’s sons, establishing Dvaraka, killing Kalayavana, abducting Rukmini, killing Paundra, Naraka with his generals, Nikumbha, Shambara and defeating Shiva’s disciple Bana after defeating Shiva and Skanda.

A link with Kalanemi is carried over from the deva-asura war through his six sons being born to Devaki and ironically being killed by Kalanemi reborn as Kamsa because of the demon king Hiranyakashipu’s curse. Varuna’s exhortation to Krishna (113.28-40) asking him to “Remember the unmanifest primordial matrix…” is very well translated. 40.17 is a fine sloka with echoes of the Rig Veda:

“Who is awake here, who is asleep? Who breathes, and who stirs not?

Who has pleasure? Who has splendour and who is darker than dark?”

He is said to fall asleep at the end of summer, and rites cease. He awakens, like goddess Durga, in autumn and his rites resume (40.23-24).

Mayavati’s falling madly in love with Pradyumna, whom she has nursed from infancy, is a unique event in puranic lore, carefully skirting the incestuous. Similarly, son-less Raja Jyamagha is so afraid of his only wife Chaitra that he introduces a young woman won in a fight as the future wife of their unborn son. Chaitra then gives birth to Vidarbha who fathers sons on that woman (called Kausalya in the next chapter) who is much older than him, very much like Pradyumna marrying his nurse Mayavati.

There are interesting details such as Vishnu’s chariot being two-wheeled (32.27) while the demon Maya’s is four-wheeled, drawn by bears, and Taraka’s has eight iron wheels drawn by donkeys. A curious detail regarding the barbarian invader Kala-yavana is that his horses’ foreparts were bull-like. Indra’s chariot fitted with a pennant atop a bamboo pole and his annual festival celebrated by Uparichara Vasu’s raising such a flag resemble the occidental Maypole festival. Varuna brandishes the snares of death, a memory of his supreme status in the Rig Veda. Another feature is that many gods and demons have the same name, e.g. Varaha, Hayagriva, Vamana, Vaishvanara. Svarbhanu (the name used in HV for Rahu, the eclipse) is extolled repeatedly. Surya has not much of a role. Catapults and machines that kill a hundred at a time (shataghni) are mentioned often.

HV states that Brihaspati’s sister Yogasiddha was mother of Vishvakarman and it was the 8th Vasu Prabhasa who became Bhishma. It provides alternative accounts of famous incidents such as Bhishma’s boon of death-at-will. While in MB Shantanu bestows it being pleased with Devavrata’s abdication and vow of lifelong continence, in HV Shantanu’s departed spirit bestows it because Bhishma strictly observes the rules of how shraddha offerings are to be made. HV further records that Vyasa’s son Shuka, celebrated as a lifelong celibate in MB, had four sons and a daughter by Pivari, mind-born daughter of the Barhishad manes. Shuka’s son-in-law is Anuha, king of Kampilya of the Panchalas. The chronology is completely garbled here because Bhallata, fourth in descent from him, is killed by Karna “long back”. Bhallata’s son Janamejaya is slain by the usurper Ugrayudha wielding a deadly discus, who demands that Bhishma give up the newly widowed Satyavati to him. Bhishma kills him and restores the Panchala kingdom to Drupada. MB does not know this episode. Soon thereafter Arjuna defeats Drupada and gives Ahichhatra and Kampilya to Drona.

A very interesting episode is the tale of how Lake Acchoda came to be born as the fish-born daughter of Vasu and Adrika in the 28th Dvapara Yuga. Another is that after Brahma created the gods, expecting they would worship him, they made offerings to themselves instead, whereupon ignorance overwhelmed creation. On their repenting, Brahma directed them to seek knowledge from their children, explaining that the gods and their offspring were fathers of one another. That is the origin of the manes and the reason for offerings to be made to them first in any rite.

The rishis are not vegetarians. Satyavrata, exiled by his father from Ayodhya, provides deer, boar, cow and buffalo meat to Vishvamitra’s family in his absence and liberates the rishi’s son Galava who was being sold by his mother to sustain the family during a 12 year drought. In Kurukshetra, seven sons of Kaushika sent out to graze their guru’s cow eat it up driven by hunger. Offering the flesh of animals in yajnas is highly extolled.

Interesting light is thrown on barbarians. The Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Paradas and Pahlavas, sought to be exterminated by Sagara, take refuge with Vasishtha. Sagara spares them but prohibits these kshatriyas Vedic rites, so also for Kolisarpas, Mahishakas, Darvas, Cholas and Keralas. He enforces half-shaven heads for Shakas, fully shaven for Yavanas and Kambojas, unshorn hair for Paradas and uncut beards for Pahlavas. Central Asian tribes who invaded India had such strange appearances. It is these very mlecchas that Vasishtha calls upon to defeat Vishvamitra’s onslaught. The lands Sagara conquers are of interest too (the CE omits this): Khasa, Tukhar/Tushara, Cheen, Chola, Madra, Kishkindhak, Kauntal, Banga, Shalva and Kaunkan. This indicates that the north-west, north-east, east and south were beyond the Vedic pale.

The birth of Sagara’s sons prefigures that of Dhritarashtra’s. Rishi Aurva grants Sagara’s junior wife the boon of 60,000 sons. She delivers a bottle-gourd containing embryos that are placed in ghee-filled pots, just as Vyasa does later with Gandhari’s embryo. In Sagara’s lineage Rama’s son is named Kusha and the line follows his descendants, ending with Sahsvat. There is no mention of his twin Lava. The CE omits the verses that take the line up to Brihadbala who is killed by Abhimanyu at Kurukshetra.

Soma the moon is the first to perform the rajasuya yajna and waxes arrogant, even abducting his guru Brihaspati (Jupiter)’s wife Taraka (asterism) called Tara in the vulgate. Ushanas-Shukra (Venus) and the demons espouse Soma’s cause while Rudra (Orion) wields his bow on Brihaspati’s side. Tara’s son by Soma is Budha (Mercury) who rises opposite him in the sky. The references to celestial events are clear. Budha is the progenitor of the Lunar Dynasty whose capital is founded by his son Pururavas at Pratishthana. The CE unfortunately omits the fascinating tale of how Pururavas obtains the heavenly threefold fire from the Gandharvas on Urvashi’s advice, finding it hidden within a fig tree and kindled by churning its wood.

HV resolves the puzzle why Indra is also called Kaushika in MB and elsewhere. Inspired by the ascesis of King Kushika, Indra takes birth as his son who is also named Gadhi. How Jamadagni, Parashurama, Vishvamitra and Shunahshepa came to be born is also told here, which the CE omits. When Indra loses his kingdom to King Raji’s sons, Brihaspati leads them astray into abandoning the Vedas and righteousness whereby they lose power and can be slain by Indra. This is the reference to Brihaspati as the author of atheistic doctrine (Buddhism, Jainism, Charvaka) that culminates in Kautilya’s Arthashastra.

HV provides a detail missing in MB. It specifies that while installing Puru in the centre as king, Yayati appointed the eldest Yadu in the north-east, Turvasu in the south-east, Druhyu in the west and Anu in the north, where their descendants continued to govern. Another origin story is that of the eastern gangetic delta peoples. Anga, Vanga, Suhma, Pundra and Kalinga are sons of the eponymous Bali, the demon monarch reborn as human. A link is found with the Ramayana because Anga’s descendant Dasharatha was known as Lomapada whose daughter Shanta (said to be daughter of Ayodhya’s Dasharatha) produced Chaturanga Dasharathi by Rishyashringa. Chaturanga’s son is Champa who made Malini his capital renaming it as Champaa, which was later Karna’s capital. Among Chaturanga’s descendants (or successors) Karna and Vikarna are named.

An important detail regarding the questionable royal pedigree of the Bharatas is that Bharata’s sons were destroyed because of their mothers’ rage and he adopted either the sage Bharadvaja himself or his son named Vitatha (“In Vain”) as his successor. Thus, Janamejaya, who is listening to the recital, is actually of Brahmin descent. A curious omission while naming Ajamidha’s descendants is that although Jantu is named, there is no mention of his being sacrificed in a yajna to obtain a hundred sons for Somaka as in MB. It is clarified that the genealogy contains two Rikshas, two Parikshits, three Bhimasenas and two Janamejayas. Only Vichitravirya is named as Shantanu’s son, not Chitrangad and Devavrata, presumably because neither had any progeny. Of Pandu’s sons only Arjuna is mentioned since he is the direct ancestor of Janamejaya.

Here Pandyas, Cholas, Kolas and Keralas are said to be sprung from Duhshanta’s grandson Sharutthama. Duhshanta, descendant of Yayati’s son Turvasu, gets absorbed into Puru’s lineage to become king and fathers Bharata. Gandhara is named after Yayati’s son Druhyu’s eponymous descendent and is famed for its horses. Yayati’s son Anu’s line is traced only up to Suchetas in the fifth generation. It is ironic that the lineage of Yayati’s disinherited eldest son Yadu should include Arjuna Kartavirya, the most famous emperor ruling over the seven lands and a disciple of Vishnu’s avatar Dattatreya. Vasishtha’s curses him that because of destroying his ashram he will be surpassed by Arjuna Pandava and slain by a Bhargava Brahmin (the next avatar Parashurama). The Rama-avatar occurs in the 24th yuga and the killing of Lavana is credited to him instead of Shatrughna. Through Yadu’s progeny the Hehayas several clans emerge (Vrishnis, Madhavas, Bhojas, Avantis, Talajanghas etc.) who dominate western India. Krishna descends from Yadu’s son Kroshtu by his second wife Madri. His grandson Shura had Vasudeva and nine other sons, plus Pritha and four other daughters (Prithukirti, Shrutadevā, Shrutashravā and Rājādhidevi) from whom Kamsa, Shishupala, Dantavaktra and Ekalavya wre born–Krishna’s cousins and mortal enemies. Jara, Krishna’s killer, was his step-brother from Vasudeva’s Shudra wife and became lord of Nishada bowmen. Ekalavya was the son of Vasudeva’s brother Devashrava, but being brought up by Nishadas was called Naishadi, and lived on mount Raivata near Dvaraka.

The rate of taxation was fixed as one-sixth of the produce. Those not paying tax had to be looked after by the ruler. HV explains the necessity for devastating wars. Over-population burdens the earth, which has no space left. Brahma recommends that, retaining the virtuous people, only kings be killed. That, of course, means that their fourfold armies will also have to be slaughtered.

A new origin story of the primordial demons Madhu and Kaitabha is given. After they emerge from Vishnu’s ears like logs, Brahma has the wind vivify them, naming the softer one Madhu and the hard one Kaitabha. Vishnu squeezes them to death and their fat, absorbing the primordial ocean, becomes the earth. There is an additional tale to the MB account where the earth states that after Parashurama eradicated Kshatriyas 21 times, she begged Kashyapa for kings, whereupon the Ikshvaku dynasty ruled over her. Again, it is when Brahma is listening to Kashyapa narrate ancient tales that the ocean and Ganga drench him. Brahma curses the ocean (and not Mahabhisha as in MB) to be born as Shantanu (because he ordered the ocean to calm down and be embodied) with Ganga as his consort.

An interesting chronological clue is provided: the meeting of the gods on Mount Meru with Vishnu and Brahma occurs when Pandu and Dhritarashtra have got married. The gods are commanded to distribute themselves as their progeny and cause a massacre of royalty to relieve the earth’s burden. Brahma prescribes that Dharma’s portion must go to Kunti or Madri and that of the god Kali to Gandhari. Reassured, the earth departs with Kala (time or death). Here Vasudeva is a portion of Kashyapa born as a cattle farmer at Govardhana mountain. Brahma asks Vishnu to be born to both Devaki and Rohini. Leaving his ancient body in Parvati (an inaccessible cave on Meru) Vishnu takes birth in Vasudeva’s house. How Vasudeva manages to evade guards and take the infant to Yashoda, returning with her new-born girl, is not told. It is Vasudeva who informs Kamsa that a girl has been born. Vasudeva makes Nanda shift to Vraja, not revealing that Yashoda’s boy is actually his own son, asking him to avoid Vrindavana. That is where Krishna has the community shift to later when Vraja gets deforested, polluted with cowdung and urine and is attacked by wolf-packs that he creates to make them leave. In chapter 96, however, Narada says that using wolves Krishna scared away Kamsa’s brother Sunaman who came with troops to capture him. It is strange is how Nanda, keeper of Kamsa’s cows, is able to shift station to Vraja and then to Vrindavana without his master’s knowledge.

The cart baby Krishna overturns and the two trees he uproots while crawling are not superhuman beings in HV as they are in the later Bhagavata Purana. Sankarshana is named Baladeva (the strong god) after he shatters the demon Pralamba’s skull with his fist. It is in this chapter 58 that Krishna reminds Sankarshana of his true self as Ananta the Endless and Shesha the Remainder, the serpent upon whom the world rests.

Chapter 59 in its explanation of the Shakra festival at the end of the monsoon provides a fine interpretation of the Rig Vedic myth of the celestial cows and their liberation by Indra riving apart the clouds, thus milking the sun’s cows. Just as Brodbeck glosses Parjanya as “the water-giver” (59.17) he should not have omitted Purandara before “smasher of citadels” (59.7). He does not gloss Shatakratu (78.41, performer of a hundred rites). At the three-day-long mountain-festival Krishna introduces, first buffaloes are killed for food. The cowherds feast on seasoned meats with rice. This Govardhana episode includes the mini-myth of Indra relinquishing two of the four monsoon months to create the season of autumn when the sun will move into the Southern Cross (Trishanku) and the star Canopus (Agastya). Indra tells Krishna about Arjuna’s birth as his portion and requests that he befriend and protect him for the Bharata War. Replying, Krishna reveals his awareness of the birth of the Pandavas and Karna, promising to do whatever Arjuna asks him to. Chapter 64 describes milkmaids dancing and romancing Krishna that became famous later as “raasa-leela” in the Krishna-bhakti movement, but there is no mention of Radha.

There are thematic similarities with the Ramayana, such as Krishna breaking the massive bow of Kamsa’s yajna and his killing numerous demons in the forest, but the moonlit dancing with milkmaids is all his own. There is also the strange incident of his smashing the skull of Kamsa’s dhobi simply because he will not give him clothing dyed for Kamsa. The two wrestlers who try to kill Krishna and Baladeva are from Andhra and Karusha ( in Central India). Krishna’s manner of dealing out death is quite horrific: splitting Keshin in two, ripping out Arishta’s horn and Kuvalyapida’s tusk and beating them to death with those, smashing Chanura’s skull so that his eyes pop out (as Sankarshana does with Mushtika). From the lament of Kamsa’s wives we learn that he had destroyed Jarasandha’s troops (77.26). Kamsa’s mother in her lament quotes a verse uttered by Ravana that it is relatives that bring misfortune despite all one’s potency (77.44-45). Krishna even repents hearing all the lamentation (78.2-6).

There is a detailed description of how a stadium should be prepared for tournament in Kamsa’s instructions (72.2-11 and 74.2-15) which is not found in the epics. Kamsa reveals that he was actually fathered by the demon Drumila, lord of Saubha, deceiving his mother Suyamuna by assuming Ugrasena’s appearance, very much like Uther Pendragon deceiving Igraine to produce Arthur. Of course, Vishnu himself deceives Vrinda by assuming the form of her husband Jalandhara.

During the stay in Mathura, Balarama revisits Vraja by himself where the cowherd community appears to have resettled from Vrindavana after having abandoned it initially under Krishna’s urging. On this occasion, Baladeva changes the course of the Yamuna so that it flows through Vrindavana.

Gonarda, the king of Kashmir, the only monarch missing from the Kurukshetra War, is mentioned as besieging Mathura as an ally of Jarasandha, along with Virata (with whom the Pandavas live in disguise later), Ekalavya (a cousin of Krishna like Shishupala, Dantavaktra and Jara), Shalya (maternal uncle of Nakula and Sahadeva) and the Kauravas. One wonders how Bhishma permitted this. Was he apprehensive of Jarasandha? Did the Kauravas include the Pandavas? How did Kunti countenance an alliance against her brother’s son and her kin?

In sections dropped by the CE Vikadru narrates how the Ikshvaku dynasty’s Haryashva was exiled from Ayodhya by his elder sibling and settled in his father-in-law Madhu’s town inhabited by Abhira cowherds. This kingdom came to be called “Anarta/Surashtra”. Haryashava’s son was named Yadu, whence the Yadavas. Yadu’s great grandson Bhima is Rama’s contemporary and his son Andhaka is Kusha’s. Mathura is not fortified, its moats are dry with no stores of materials to withstand a siege because of Kamsa’s neglect. The troops are disheartened facing repeated onslaughts (as many as 18 plus Kalayavana’s attack). Thereupon Krishna and Balarama proceed south-west to the Sahyadris to meet Parashurama on Mahendra mountain, who has established the town of Shurparaka by “pushing back the sea”. He advises them to take shelter on Gomanta peak and fight Jarasandha there.

Krishna leads the Yadavas away from Mathura to the mountain Raivataka in the far west. Ekalavya’s home is nearby. On a large piece of land like a gaming board named Dvaravati Krishna establishes the city of Dvaraka marking it out with measuring tapes, with three-and-four-way crossroads. Such details are not found in MB for Indraprastha whose construction is quite mythical. As with the earlier avatar Parashurama establishing Shurparaka reclaiming land from the sea, here the new avatar Krishna reclaims an area of the sea-bed 10 yojanas-by-2 yojanas (86.36). Krishna sets out codes of conduct for citizens, constitutes guilds, appoints troop-commanders and, a council of ten elders with Raja Ugrasena.

Kalayavana, the deadly barbarian, attacks leading a horde of Shakas, Tusharas, Daradas, Paradas, Tanganas, Khashas, Pahlavas and Himalayan barbarians. There is a very interesting passage about embassies here. Krishna sends Kalayavana a sealed pot containing a vicious snake. The pot is sent back filled with ants who bite the snake to death. Finding himself trumped, Krishna leads the Vrishnis away to Dvaraka. After the ancient king Muchukunda has consumed Kalayavana, Krishna intimates a strange fact: at present it is the Kali Yuga (85.59). However, according to MB the Kurukshetra War occurs at the end of the Dvapara Yuga with Kali beginning after Krishna’s death. This is yet another piece of information that needs to be reconciled with MB. In HV the Kali Yuga is called Maheshvara’s age in which people worship him and Kumara (significantly, both are non-Vedic gods), are ruthless and short-lived.

HV explains Shishupala’s loyalty to Jarasandha. Shishupala’s father Damaghosha had given him away to his kinsman Jarasandha who treated him like his own son (87.22). To please his foster father, Shishupala made mischief against his maternal uncle’s clan, the Vrishnis, because Krishna had killed Jarasandha’s son-in-law Kamsa. Jarasandha was overlord of Anga, Vanga, Kalinga and Chedi, i.e. Bihar, Bengal, Orissa and Bundelkhand. Rukmini’s father Bhishmaka was king of Vidarbha (Nagpur area). In the battle following Krishna’s abduction of Rukmini, Balarama killed the king of Vanga and his elephant with a tree (which we find Bhima doing frequently in MB). As we find in MB as well, elephant armies were the speciality of Vanga, Kalinga and Pragjyotishpura (Assam).

After the marriage with Rukmini, seven other wives of Krishna are specifically named and 16,000 other wives are mentioned. Despite the enmity with her brother Rukmin, there is no problem in Rukmini’s son Pradyumna marrying his maternal uncle’s daughter Shubhangi, and Pradyumna’s son Aniruddha wedding Rukmin’s grand-daughter Rukmavati. In the dice-game engineered by Rukmin after the wedding he defeats Balarama by cheating—a parallel to the MB dice-game—and insults him, whereupon Balarama kills him with the gaming-board.

Chapter 96 introduces Ekanamsha as Devaki’s daughter, though born to Yashoda, as she grew up with the Vrishnis. She stands with Balarama holding her right hand and Krishna her left, exactly as depicted in the icons in Puri’s Jagannatha temple and also in a sculpture in Mathura from the early common era.

In Krishna’s battle against Naraka’s hordes it is abruptly mentioned that many fell to his plough, conflating him with Balarama. When Krishna goes to Svarga to return Aditi’s earrings stolen by Naraka, abruptly, without any reason, he carries off the celestial Parijata tree (Mandar/Kovidar) to Dvaraka. The reason has been explained at length in the vulgate, viz. to fulfil Satyabhama’s desire to observe the “punyaka” vow to outdo Rukmini, instigated by Narada. This episode, describing Satyabhama’s sulking, is very similar to that of Kaikeyi in the Ramayana. After the tree has been replanted in Dvaraka, Krishna brings the Pandavas, Draupadi, Subhadra and Kunti there, as also Shishupala with his mother, Bhishmaka and Rukmin. Therefore, this occurs during the Indraprastha period before the rajasuya yajna. After a year, Krishna returns the tree to Svarga. Satyabhama is celebrated as the best of women (Brodbeck’s “in terms of beauty” is gratuitous) and the most fortunate, while Rukmini is the supreme mistress of the household (94.27). After this, Narada recounts to the Yadavas Krishna’s deeds and foretells that the sea will reclaim Dvaraka after his death (chapter 97).

Krishna’s killing of two spies of Ravana (97.8) is puzzling and Brodbeck has not annotated this. Krishna is said to have defeated Yama and brought Indrasena’s son back (97.12) as he did Sandipani’s, but no details are given about Indrasena’s identity. Krishna is also said to have defeated Arjuna in Kunti’s presence (97.17) as also Drona, Ashvatthama, Kripa, Karna, Bhima and Duryodhana all together. Again there is no annotation of this intriguing mention. This tale, not told in HV, is found in Girish Chandra Ghosh’s Bengali play “Pandav Gaurav” (1901) which is based upon the apocryphal Dandi Parva of the MB (cf. my “When The Eight Vajras Assembled” https://pradipbhattacharya.com/2022/09/14/when-the-eight-vajras-assembled/). At a yajna performed by Duryodhana, all the attending kings, hearing of Krishna’s glory, proceed to Dvaraka to establish alliances with him. Here HV mentions the Dhartarashtras, Pandavas, Panchalas, Pandyas, Cholas, Kalingans, Bahlikas, Dravidas and Shakas.

Problems of Translation

Those unfamiliar with Tolkien’s world will be unable to make out what Brodbeck intends to convey by rendering Gandharvas as “light-elves”. The elf is a tiny, delicate, magical creature in human form with pointed ears while Gandharvas are magical warriors and celestial musicians. Yakshas are termed “dark-elves,” although these demi-gods are not always malevolent and might be rendered better as “ogres” who are treasure-guardians too. The analogous Guhyakas become “trolls”; the horse-faced Kinnaras and Kimpurushas are called “mountain-elves” and “wild-elves”; Vidyadharas (sorcerers), become incongruous “sylphs”. Although rakshasa, pisaca, apsara, ashrama, rishi and dharma feature in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), Brodbeck needlessly translates them as “monster”, “fiend/devil”, “celestial nymph”, “estate”, “seer” and “virtue,” but he does not translate “Danava” and “Daitya” who are demons.

In the high-seriousness of the epic environment, his use of slang, like “crikey” and the colloquial, “daddy’, “capable fellow”, “slowcoach”, “broad-bottomed (for women)” are jarring. “Rampant” as an adjective for women (92.35) is inappropriate. He also provides English translations of Sanskrit names inconsistently, similar to the TIME magazine’s hilarious “Red Brave Lion” for “Lal Bahadur Singh”, but not for “Rukmakavacha” (gold-armoured) and Kambalabarhisha (blanket of sacred grass). Where “Vaivasvata” is rendered as “the sun’s son Yama”, why is “Vaishravana” merely “Kubera Vaishravana” and not “Vishrava’s son” (34.48)? In the same verse the army is not ‘tossed about” by Varuna as translated, but is “encircled” (parikshipta) by “the king of the waters”. Pashu, destroyed by Rudra, is translated as “cattle” instead of “beasts” (10.38). In 31.133 Brodbeck has Brahmins attending upon Kshatriyas whereas it is the other way about. When Krishna is called “maha-yogi’ by Janamejaya (85.5), it can hardly be rendered as “great trickster” as if he were another Loki. Moreover, both “maha” and “yogi” are in the OED. In 31.153 “yoga tricks” is an unfortunate translation of “yogamaya” (yogic illusion), as is rendering “yogadharmina” (whose dharma was yoga) as “tricks were his business,” when “maya” and “dharma” are in the OED. In 32.27 “bandhura” has been translated as “driving seat” whereas it means “crest” or “adorned with”. Kubera as “vimanayodhi” (34.17) is not “conqueror of aerial chariots” but “aerial-chariot-warrior”. His appellative, “naravahana” (carried by men) has been mistranslated as “transported by spirit-elves” (34.17). In 34.21 the Sun revolves from rising to setting, with no reference to the eastern and western mountains as rendered. Vishnu does not make Danava women “stray beyond their boundaries” (38.8) but removes the auspicious mark in their hair-parting, i.e. makes them widows. The demons are not “roasted” (“nirdagdha” 38.53) by Vishnu’s mace and discus, but “consumed”. Diacritical marks are unnecessarily used for “vina” when “veena/vina” is very much in the OED. “Vatsa” is certainly not “calf” when Devaki addresses Kamsa, but rather “child” (48.44). “Sarasa” (59.33) is not “flamingo” but “crane”; “japya” (86.1) is not “textual recitation” but “murmured prayers”; the dust raised by Keshin is not “sweet pale” but “honey-pale” (67.27) and it is his jaws that are split, not hips when Krishna thrusts his arm into his mouth (67.35). In 72.8 the correct rendering of “karisha” is not “cowdung” but “dry cowdung”. By replacing the original “Vraja” by “cattle station,” Brodbeck deprives the reader of the name of the place renowned for Krishna’s childhood. In 99.19 he describes Pradyumna as “young brave” as though he were a North American Indian warrior. In the Tarakamaya war, Brodbeck has Ushanas launch the Brahmashiras missile at the gods, whereas the vulgate appropriately has Rudra launch it at the demons causing great destruction.

Brodbeck’s translation for 26.27-8 makes no sense: “The Mother was born…The Mother’s wife was a descendant of Ikshvaku…”. The reference is to a son named “Maatu” (“Sattvan” in the vulgate, thus avoiding the confusion with mother). In the next verse (27.1) Brodbeck’s adding “the Mother” to “Satvat” is gratuitous. The translation of 27.20 about Ahuka is not correct and should read: “An entourage of eighty wearing white with leather shields marched ahead first of the great one energetic as a colt.” Brodbeck does not annotate the reference in 66.5 to a prince of the Ikshvakus who left. This is Sagara’s son Asamanja who was exiled for his wickedness. 98.24 is mistranslated as, “But Vajra was born before that. Vajra was the son of Aniruddha and Anu.” It should read, “Aniruddha had two sons Sanu and Vajra, but Vajra was born earlier.” In 99.3 “kala” Shambara is not “dark” but “deadly” and in 99.4 Krishna does not “practise the magic of the gods,” but “complying with deva-maya” he does not seize the demon. At 108.3 Aniruddha is compared to “Ilavila’s son Kubera,” which is confusing in the absence of the gloss that Ilavila is sage Vishrava’s wife.

In 3.63 Bana does not ask Shiva for a pleasure garden near him, but wishes to enjoy, staying by his side. The appellative “shitikantha” for Shiva is more appropriately “dark-throated” instead of “dark-necked” (106.19) as the poison he had drunk turned his throat dark blue. Bana captures Aniruddha by immobilising him with snake-nooses just as Indrajit did with Rama and Lakshmana (108.84). The Aniruddha-Usha episode is like a fairy tale replete with the magical and the erotic, similar to the Kathasaritsagara tales.

One of the delights of HV is Brodbeck’s splendid translation of the war between the gods under Indra and the demons led by Maya spanning several chapters. The gods are not immortal, nor are the demons. They are decapitated, chests smashed, cut to pieces. Yama, despite wielding the fatal rod, cannot destroy demons. Soma the moon and Varuna lord of waters join to freeze the Daityas. The demon Kalanemi (Death’s Rim) features prominently, even immobilising immortal Yama the all-destroyer. In the Adhyatma Ramayana Kalanemi is Marich’s son and is killed by Hanuman. Later, he is reborn as Kamsa along with other demons for killing whom again, at Narada’s urging Vishnu has to take birth where Brahma specifies. No Occidental epic other than Milton’s has anything like the exciting description of the Tarakamaya war between gods and anti-gods. Only Bali and Svarbhanu escape Vishnu’s onslaught. There is repeated reference to weapons made of the finest iron, which indicates that the composition is post-bronze age. Chapter 54, describing the monsoon and the description of the beauty of boy Krishna in Chapter 55 are mellifluously translated.

Bhavishya Parva

Bhavishya Parva starts with Shaunaka querying the bard Suta about Janamejaya’s descendants. Brodbeck’s translation of 114.10, “the august child’s storm clouds were made manifest” makes no sense. The last name in the Pandava dynasty—traced back to Puru—is the orphan Ajaparshva raised by two Brahmins in a weaver’s house.

The story of how Janamejaya came to prohibit performance of the horse-sacrifice is told. First he points out to Vyasa that the destruction of the Kurus arose from Yudhishthira’s rajasuya rite, which has always brought destruction in its wake beginning with Soma, followed by Varuna and Harishchandra. He asks Vyasa why he did not guide Yudhishthira. Vyasa replies that as he was not asked about the future, he did not reveal it and anyway time’s course is unalterable. Vyasa warns Janamejaya that he ought not to perform the horse sacrifice as Indra would attack it and Brahmins would be antagonised. Vyasa also foretells that in the Kali Yuga a Brahmin army general will revive the ashvamedha and also perform the rajasuya. This is a clear reference to Pushyamitra Sunga (c. 185 CE). Typically, Janamejaya forgets Vyasa’s warning and holds the horse-sacrifice in which Indra animates the suffocated horse and has coitus with the queen lying beside it. The priest reveals the truth whereupon the furious king bans the ashvamedha and exiles the priests.

A description of the degenerate social conditions of that age follows. An interesting feature of it is that nanny goats (not Brodbeck’s male “billy-goats” who cannot give milk) will be kept as milch animals, reminiscent Mahatma Gandhi’s preference. It also tells of climate change, ponds ploughed over, drought, infertile soil, prevalence of Shiva-worship, beggars proliferating, shudras following Buddha of Shakyas wearing ochre robes with shaven heads and collyrium-marked eyes (not Brodbeck’s “uncowed eyes”) and education being sold. In 116.33 the original of Brodbeck’s “he-men” is not found. He translates “gavedhuka” (116.35) as “tear-grass” whereas it is a mallow plant (Sida Alba). The name for this yuga used in 117.11-14 is “kashaya,” one sense of which is the ochre robe worn by Buddhist monks, i.e. this evil era will witness prevalence of Buddhism besides neglect of Vedic deities. Conversely, Vyasa also foretells that pure people will attain salvation quickly (117.13) at the time of the ochre affliction. Refugees will flee across the River Kaushiki (Kosi) and abound in Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Kashmir, Mekala (Deccan) and hilly Rishika (not “River Rishika” 117.29), on Himalayan slopes, sea shores and forests, reverting to hunting from agriculture. Clearly, these places were considered outside the Vedic pale. The tide will turn when, with the proliferation of sadhus, people will be obsessed with having their darshan and give up desires to pursue truth (117.40), whereby the golden age will be renewed. The CE ends with Suta extolling the benefits of listening to this Purana and asking what else Shaunaka would like to hear. Brodbeck provides a fine rhythmic translation of the conclusion (117.51):

“The cycles of ages were set up of old

by nature and command,

so not for a moment do creatures stay put:

changing they fall and they stand.”

This is where the vulgate takes off with a different version of creation, the deva-asura wars and Vishnu’s avatars till Vamana, the dwarf. Then it suddenly recounts Krishna’s ascesis at Kailasa to please Shiva for obtaining a son as Rukmini desires. HV does not repeat the account of Krishna’s similar ascesis for fulfilling Jambavati’s desire for a son, Samba, related in MB. At Badari occurs a fascinating encounter with two pisacas eager to meet Krishna for salvation as advised by Shiva. They are the Ghantakarnas, bells hanging from their ears to drown out any mention of Vishnu whom they used to hate. With great devotion they offer Krishna half the corpse of a Brahmin. Politely declining, Krishna transforms them into celestial beings and proceeds to Kailasa to practise ascesis for 12 years. When Shiva appears, the hordes appearing with him are led by Ghantakarna (chapter 86). Harindranath and Purushothaman have found temples dedicated to this pisaca (cf. http://www.dvaipayana.net/krishnanattam/ghantakarna.html). Tagore’s short story “Shey (He)” mentions the two Ghantakarnas also. Shiva grants Krishna and Rukmini a son, Pradyumna, who is the god of love Kama reborn. Later, Shiva’s destruction of the triple cities of demons is narrated.

In Krishna’s absence Paundraka Vasudeva attacks Dvaraka with Ekalavya who, fighting against Balarama, flees to an island after Krishna kills Paundraka. Ekalavya’s death is not mentioned. At Durvasa’s request at Pushkara, Krishna kills Hamsa and Dimbaka of Shalva city, allies of Jarasandha. They scorn Bhishma as aged and weak and demand that Krishna surrender all his riches and provide salt for their rajasuya yajna. In this battle Balarama kills the rakshasa Hidimb exactly as Bhima kills his namesake in MB. Hamsa and Dimbaka proceed from Pushkara to Govardhana mountain and Krishna drowns the former in Kaliya’s lake in the Yamuna, whereupon Dimbaka commits suicide. It is after this that Yudhishthira performs his rajasuya yajna (chapter 29.10), which is another chronological milestone to be collated with MB. Nanda and Yashoda come to meet Krishna here. There is no Radha.

The gifts to be given to the narrator at the end of each MB parva are enumerated, specifying a book with gold. However, like in the Spitzer manuscript list, Anushasana Parva (32.68) is not mentioned. It might be subsumed in the Shanti Parva. At the end of HV the king is asked to feed a thousand Brahmins and present a cow along with gold coins. After extolling MB and HV, a summary of the HV episodes is given in chapter 34. The Padma Purana contains 5 chapters on the glory of HV plus one on the mantra for obtaining progeny.

[1] P. Lal: The Mahabharata of Vyasa, The Complete Adi Parva, Writers Workshop, Kolkata, 2013, p. 70.

[2] D.K. Printworld, New Delhi, 2015.

[3] http://mahabharata-resources.org/harivamsa/harivamsa-cs-index.html

[4] Simon Brodbeck: Krishna’s Lineage—The Harivamsha of Vyasa’s Mahabharata, Oxford University Press, 2019, pp. 420, Rs.1295.

[5] https://alt.cardiffuniversitypress.org/articles/abstract/10.18573/alt.45/

[6] Krishna in the Harivamsa, vols. 1 (2015) and 2 (2017), DK Printworld, New Delhi.

[7] “Why Harivaṁśa calls itself the Khila of Mahābhārata? – A Critique of the BORI Critical Edition of Harivaṁśa” in Mahabharata Manthan, vol. 2, pp. 319 ff., ed. Neera Misra, Rajesh Lal, BR Publications, Delhi, 2019.

[8] I have amended Brodbeck’s translation in the interests of rhythm.

[9] A. Hiltebeitel: Freud’s Mahabharata, OUP, 2018, p. 4.

[10] A. Purushothaman and A. Harindranath: “Fight between Narakasura and Satyabhama in Harivamsa…” in Aesthetic Textures, Living Traditions of the Mahabharata, ed. Molly Kaushal, S. Paul Kumar, IGNCA & DK Printworld, New Delhi, 2019.